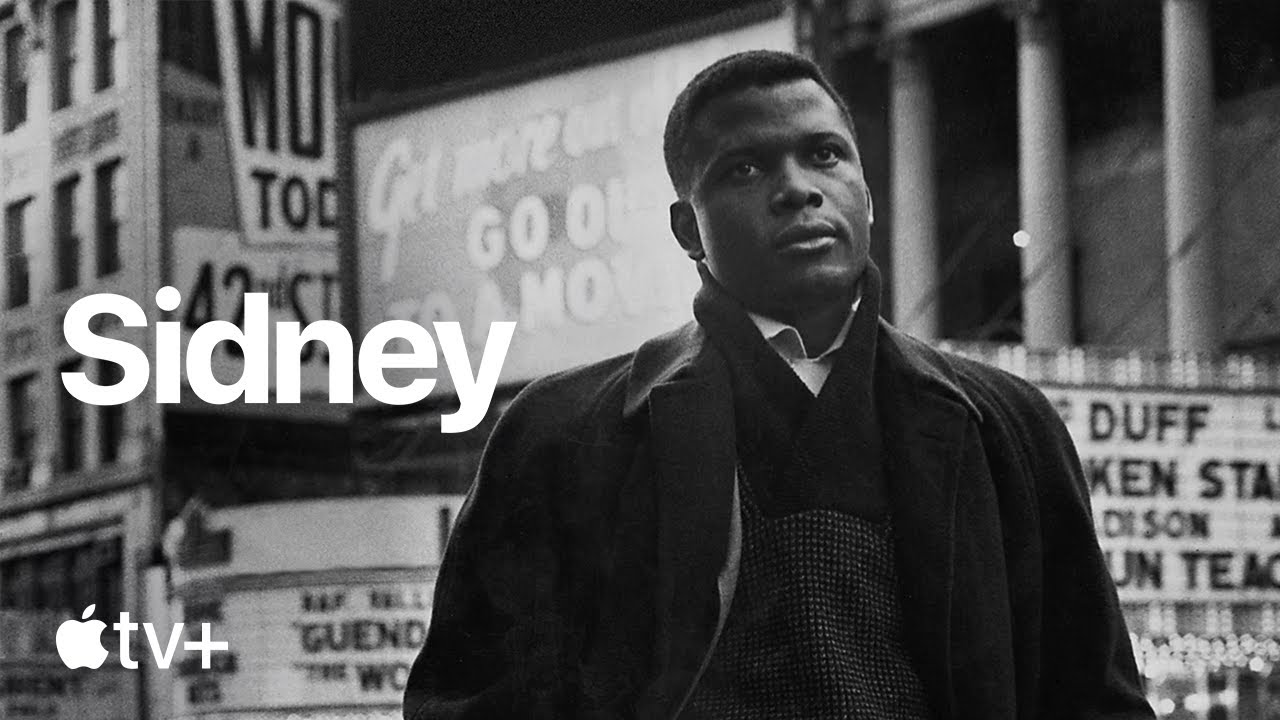

Sidney Poitier Is Back on the Big Screen

The late and great actor and director is the subject of ‘Sidney,’ a new documentary produced by Oprah Winfrey

:focal(2217x1457:2218x1458)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/00/3a00ae15-dbd9-4dd2-bcbf-d0b46d0fd8e9/gettyimages-105078823.jpg)

“I was not expected to live.” Those are the first words uttered by Sidney Poitier in Sidney, a new documentary about the trailblazing actor. The quote is in reference to Poitier’s premature birth in 1927; his mother’s midwife predicted he would die imminently.

Of course, Poitier didn’t die as an infant. Instead, he went on to lead a prolific acting and directing career that opened doors for Black artists in Hollywood and cemented him as one of the greatest American actors of the 20th century. That life and career is at the center of director Reginald Hudlin and producer Oprah Winfrey’s Sidney, which began streaming on Apple TV+ on Friday, eight months after Poitier’s death at age 94.

Born in Miami, Poitier spent his early life in the Bahamas’ Cat Island and Nassau. He moved back to Miami at 15, and then to New York City at 16. In the Bahamas, Poitier grew up in a majority-Black community, he explained in a 2012 interview with Winfrey, which makes up the majority of Sidney. He didn’t think anything of the color of his skin until he returned to Miami.

The color of Poitier’s skin, though, mattered a lot as he forged an acting career in a white-dominated Hollywood. His rise to stardom began in 1955, when he played a high school student in Blackboard Jungle. In 1964, after starring in Lilies of the Field, Poitier became the first Black actor to win Best Actor at the Academy Awards. Three years after that, he shattered more glass ceilings by starring in two of the highest-grossing films in 1967—Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and To Sir, With Love—as well as that year’s Best Picture winner, In the Heat of the Night. Poitier achieved firsts from the director’s chair, too: With Stir Crazy, he became the first Black director to make a film that grossed $100 million.

Poitier, beloved in his time by white movie-going audiences, was a complicated figure for some Black people. Sidney is full of interviews with those who applaud him, uncompromisingly, for the doors he opened—including Winfrey, Morgan Freeman, Lenny Kravitz, Spike Lee and Denzel Washington. But it also highlights the viewpoint that through his roles, he appeased white audiences by acting subservient and reinforcing Black tropes. “His movies were not made for Black people,” the late cultural critic Greg Tate says in the documentary.

The film cites a 1967 article written by critic Clifford Mason for the New York Times headlined, “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” In it, Mason describes “the same old Sidney Poitier syndrome: a good guy in a totally white world, with no wife, no sweetheart, no woman to love or kiss, helping the white man solve the white man’s problem.”

Ultimately, though, Hudlin paints a picture of a man who, in addition to delivering incredible acting performances, changed the course of Hollywood history.

“The reality is, since the invention of cinema there had been these degrading images of Black people,” Hudlin tells the Agence France-Presse. “Sidney Poitier single-handedly destroyed those images, movie after movie after movie.”