Rare Birmingham Jail Logbook Pages Signed by MLK Resurface After Decades

Two sheets of paper from the Alabama prison where the activist penned a famous 1963 letter sold at auction for more than $130,000

:focal(1011x426:1012x427)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/02/c602d8d9-6ef0-4738-ad88-22aaac951652/download_1.png)

In April 1963, Alabama police arrested Martin Luther King Jr. for leading peaceful demonstrations against racial segregation. Stuck in solitary confinement, the civil rights leader crafted what would eventually become one of the most famous defenses of nonviolent action against racism: the “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.”

Despite the missive’s wide-reaching influence, little physical evidence of King’s eight-day stint in jail remains. Though his cell door is preserved at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, the building itself was torn down in 1986.

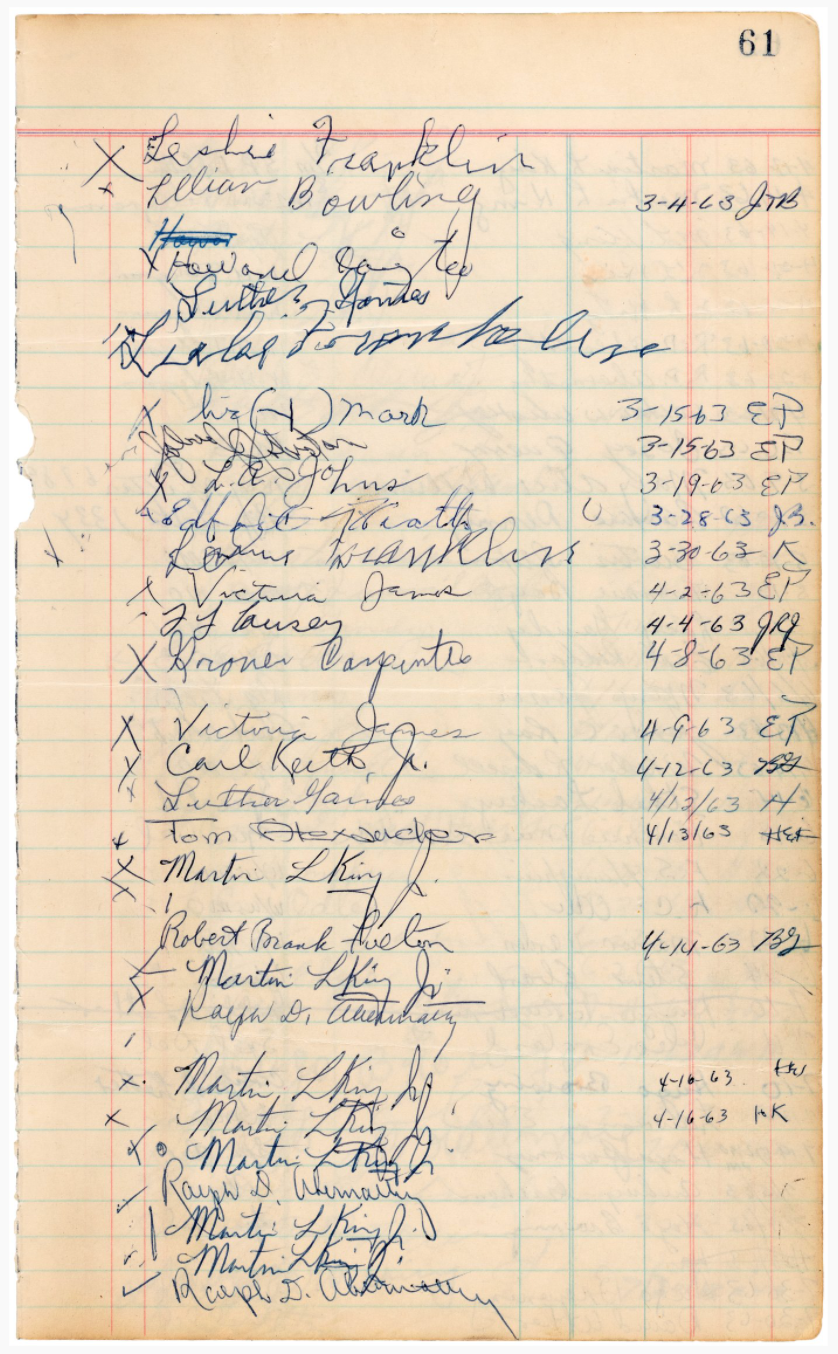

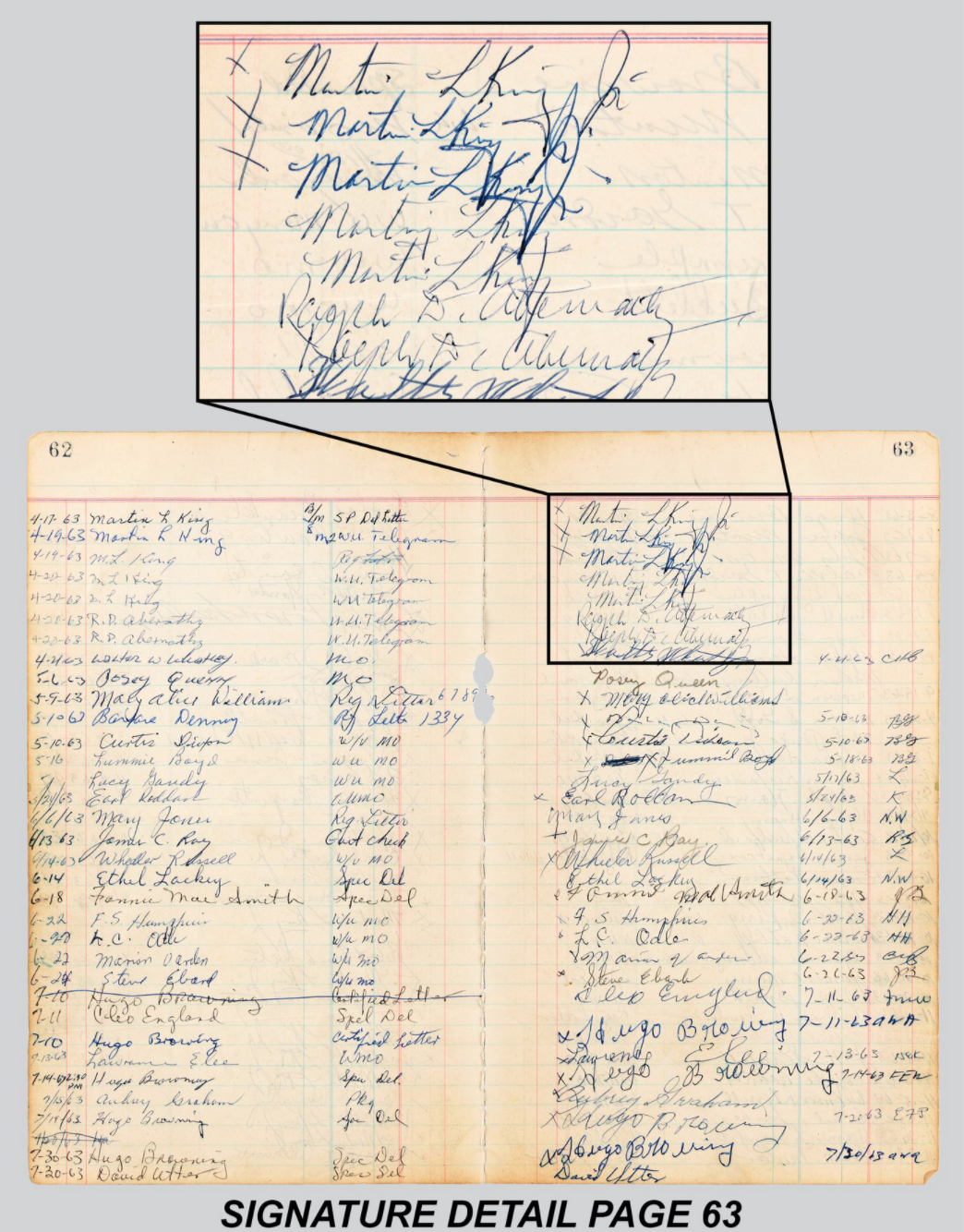

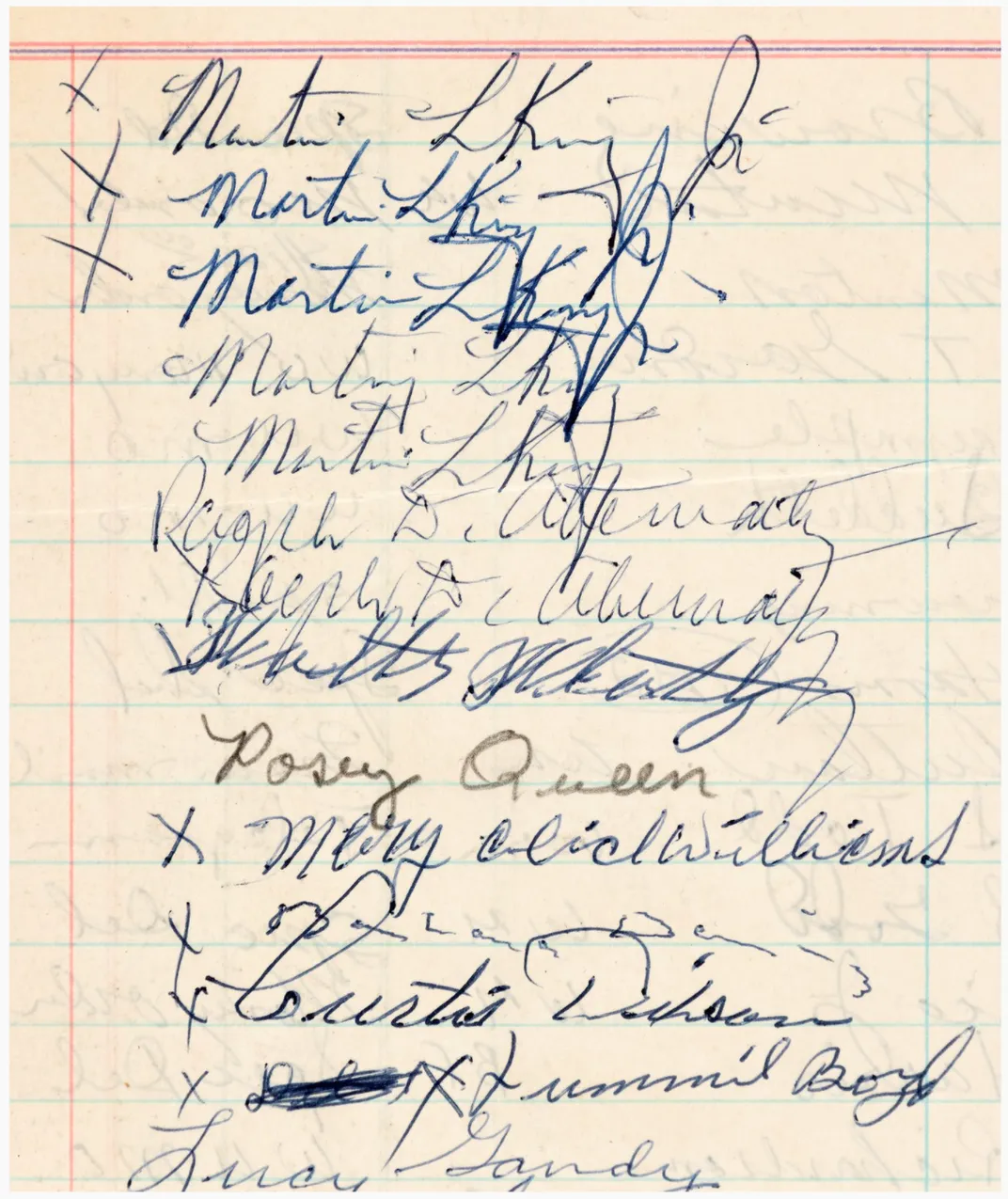

As it turns out, however, two yellowed sheets from the Birmingham jail communication log slipped through the cracks, only to resurface this year. The rare documents, which include four numbered pages of text and dozens of signatures from King and his close friend and fellow activist Ralph D. Abernathy, recently sold at Hake’s Auctions for $130,909, reports Rikki Klaus for “PBS NewsHour.”

The family that sold the work told the auction house that an employee at the jail defied orders to throw away the pages, which were eventually handed down to an avid history buff. Jim Baggett, head of archives at the Birmingham city library, tells Jay Reeves of the Associated Press (AP) that it’s possible a worker saved the log while cleaning out the building ahead of its demolition.

“We have stuff here that survived because someone pulled it out of the trash,” he adds.

Per the AP, Atlanta-based appraiser WorthPoint contracted document experts and signature authenticators to verify the pages’ veracity.

“They were trying to figure out what they had and whether it was real and what it was worth,” WorthPoint’s Will Seippel says to the AP.

Scott Mussell, an Americana specialist at Hake’s, tells “PBS NewsHour” that the find still astounds him: “Every time I sit and think about it for any amount of time, all the hair on my arms stands up.”

The pages, which recorded incoming mail for people held in the jail, indicate that King received a number of letters during his incarceration, including a Western Union telegram. He signed each entry in ink, adding an X next to his name.

Taken together, notes the Hake’s listing, the records “offer a unique glimpse of the flurry of communication occurring around King’s historic incarceration.”

According to the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference staged several mass protests, marches and boycotts in Birmingham to pressure the city to end racial segregation. (The activist once referred to Birmingham as “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.”)

King penned his famous note in response to a letter to the editor from seven Christian clergy and one rabbi, all of whom were white. In the missive, the eight authors called the demonstrations “unwise and untimely,” per the AP.

The civil rights leader’s reply—drafted in the margins of a newspaper, on bits of paper left behind by a black trustee and on legal pads left behind by lawyers—was smuggled out of the jail and eventually compiled into a mimeograph. Years later, it was reprinted in press outlets and King’s memoir, becoming one of the most famous texts on nonviolent protest in the world.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King wrote in the missive. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

He went on to criticize those who praised the police force, outline the steps of nonviolent action and decry the inaction of white moderates. Praising extremism in the face of injustice, King asked, “Will we be extremists for hate or will we be extremists for love?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)