Why Weren’t These Black Death Victims Buried in Mass Graves?

New research suggests some Europeans who died of the bubonic plague were individually interred with care

:focal(484x358:485x359)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/1b/541b9a08-4ebe-455c-bc97-f0a3133e8870/individual_burials.jpeg)

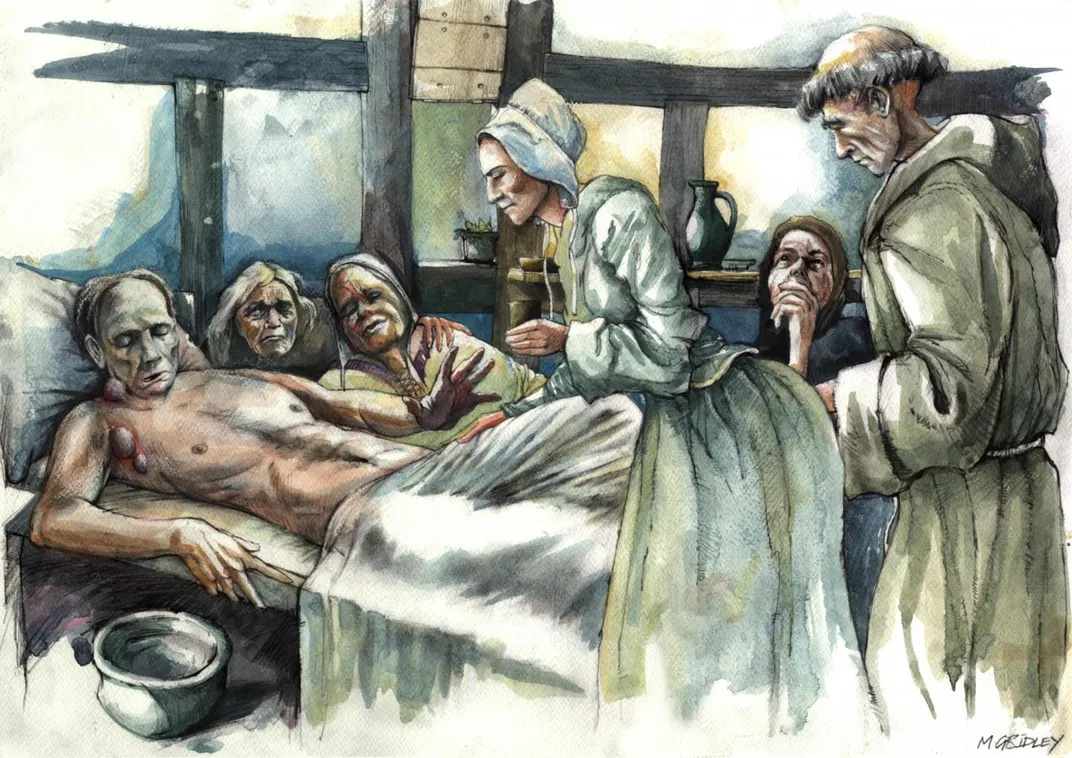

Conventional wisdom has long held that victims of the Black Death—a terrifyingly contagious disease that claimed the lives of some 40 to 60 percent of 14th-century Europe’s population—were most often buried in mass graves, or plague pits. But new research led by the University of Cambridge’s After the Plague project suggests that some of the dead actually received time-intensive burials in individual graves.

As Christy Somos reports for CTV News, the disease killed its victims so quickly that it left no signs on their bones. Until recently, the only way archaeologists could identify people who succumbed to the plague was based on their interment in mass graves, where the context of the burial was clear.

The new analysis, published in the European Journal of Archaeology, centers on people buried in Cambridge, England, and the nearby village of Clopton. Using a technique developed in recent years, scientists were able to test the skeletons’ teeth for the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the plague. They identified the pathogen in the remains of three people buried at an Austinian friary’s chapter house and another at the All Saints by the Castle church.

“These individual burials show that even during plague outbreaks individual people were being buried with considerable care and attention,” says the paper’s lead author, Craig Cessford, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, in a statement.

Clare Watson of Science Alert notes that the chapter house burials would have required significant effort. Because the building had a mortared tile floor, those digging the grave would have had to lift up dozens of tiles and either put them back in place or replace them with a grave slab.

Cessford adds that the All Saints victim’s careful burial “contrasts with the apocalyptic language used to describe the abandonment of this church in 1365.” Per the study, a local bishop claimed that “the parishioners of All Saints are for the most part dead by pestilence, and those that are alive are gone to other parishes, the nave of All Saints is ruinous and the bones of dead bodies are exposed to beasts.”

The research also documented plague victims who were buried in mass graves at St. Bene’t’s churchyard in Cambridge, reports BBC News. Following the Black Death, St. Bene’t’s became a chapel of the newly formed Guild of Corpus Christi, and the land was transferred to Corpus Christi College. Members of the college walked over the grave on their way to church.

As Mindy Weisberger reported for Live Science last year, some plague pits show signs of care afforded to individual victims. At one mass grave in southwest London, researchers noted that even though the local community was apparently overwhelmed by a surge of plague deaths, someone seems to have taken time to wrap the dead in shrouds and arrange them in rows.

“They are trying to treat them as respectfully as possible, because in the Middle Ages it’s very important to give the dead a proper burial,” excavation leader Hugh Willmott told the Guardian’s Esther Addley. “Even though it is the height of a terrible disaster, they are taking as much care as they can with the dead.”

Cessford and his colleagues argue that scholars’ long-standing reliance on mass burials for much of their information about plague victims paints an incomplete picture.

“If emergency cemeteries and mass burials are atypical, with most plague victims instead receiving individual burial in normal cemeteries, this calls into question how representative these exceptional sites are,” the authors write in the paper.

As David M. Perry reported for Smithsonian magazine in March, scholars have, in recent years, greatly expanded their knowledge of the Black Death. Using the newfound ability to track centuries-old strains of bacteria and compare them with modern ones, researchers have suggested that the plague was already spreading in Asia in the 1200s—a century earlier than previously thought.

The new findings suggest that identifying Y. pestis in skeletons buried in individual graves could provide more information about the plague’s tens of millions of victims.

“Our work demonstrates that it is now possible to identify individuals who died from plague and received individual burials,” says Cessford in the statement. “This greatly improves our understanding of the plague and shows that even in incredibly traumatic times during past pandemics people tried very hard to bury the deceased with as much care as possible.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)