Some of Edward Hopper’s Earliest Paintings Are Copies of Other Artists’ Work

Curator Kim Conaty says a new study “cuts straight through the widely held perception of Hopper as an American original”

:focal(769x495:770x496)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/45/3e450e3f-37fc-4248-94c3-75fbd416809f/hopper_composite.jpg)

Edward Hopper is known today as a quintessentially “American” painter, an artistic genius as singular as the lonely figures who populate his landscapes.

Born into a middle-class family in 1882, Hopper honed his craft at the New York School of Art, where he studied under Impressionist William Merritt Chase between 1900 and 1906.

Experts have long pointed to a small group of Hopper’s earliest creations—including Old Ice Pond at Nyack (circa 1897) and Ships (c. 1898)—as evidence of his preternatural gift for art. But as it turns out, the artist learned to paint just like many of his peers: by copying the work of others. New research by Louis Shadwick, a PhD student at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, indicates that Hopper copied at least four early oil paintings assumed to be original compositions from other sources, including instructional art magazines.

Shadwick published his stunning discovery in the October issue of the Burlington magazine. As the researcher tells New York Times art critic Blake Gopnik, he discovered young Hopper’s source material during a bout of lockdown-induced internet sleuthing this summer.

“It was real detective work,” he adds.

While Googling, Shadwick happened across an 1890 issue of the Art Interchange, a popular magazine for art amateurs in the late 19th century. It included a color print of A Winter Sunset by then-popular Tonalist painter Bruce Crane (1857-1937), alongside instructions for creating a copy of the work.

Down to the pond, the lone house and a striking band of evening sunlight, A Winter Sunset is a dead ringer for Hopper’s Old Ice Pond at Nyack, Shadwick realized in what he describes as a “eureka moment.”

As Sarah Cascone reports for artnet News, Old Pond at Nyack is currently up for sale at an estimated price of about $300,000 to $400,000. The seller, Heather James Fine Art, did not respond to artnet News’ request for comment about whether this new information would affect the work’s pricing.

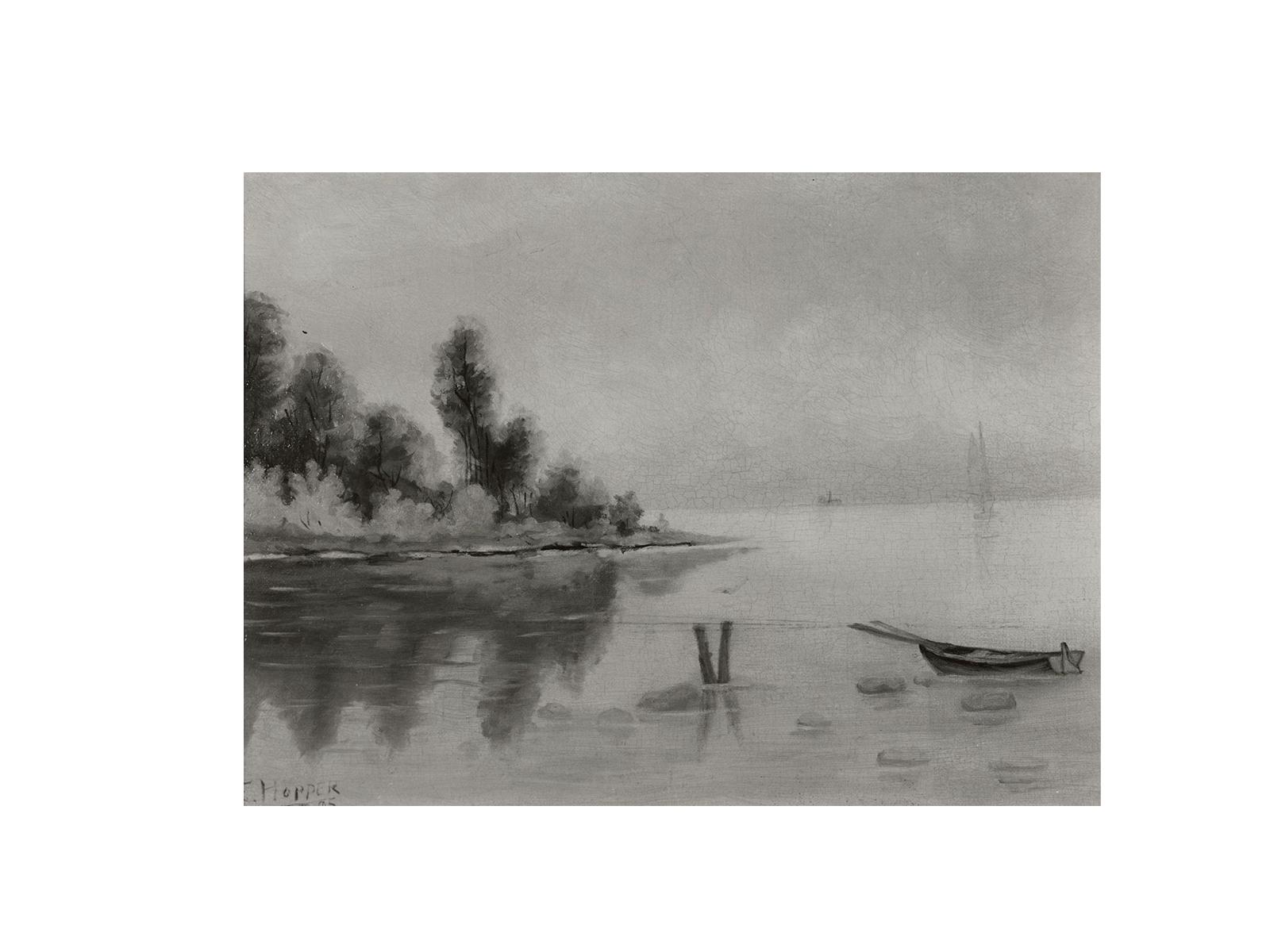

Subsequent research by Shadwick yielded an unattributed watercolor, Lake View, in an 1891 issue of the Art Interchange. The PhD student concluded that Hopper must have copied Lake View to create the work that later came to be known as Rowboat in Rocky Cove (1895); the trees, the placement of the oars in the rowboat and the posts jutting out of the water are all almost identical.

Shadwick’s research contradicts two previously accepted ideas about Hopper’s earliest works, per the Times: first, that Hopper was entirely self-trained, and second, that his earliest works were inspired by the local scenery of his childhood in Nyack, New York.

“[A]ctually, both these things are not true—none of the oils are of Nyack, and Hopper had a middling talent for oil painting, until he went to art school,” Shadwick tells the Times. “Even the handling of the paint is pretty far from the accomplished works he was making even five years after that.”

Shadwick also found that an 1880s work by Edward Moran, A Marine, matched Hopper’s Ships (c. 1898), and that Hopper’s Church and Landscape from the same period strongly resembles a Victorian painted porcelain plaque.

In the Burlington article, Shadwick traces the ownership history of the Hopper works in question, concluding that the artist never intended them for individual sale or exhibition. Local Nyack preacher and personal friend Arthayer R. Sanborn retrieved the works from Hopper’s attic following the latter’s death in May 1967. As Shadwick argues, Sanborn appears to have incorrectly conflated the content of the early works with Nyack’s scenery and proceeded to give names to what were previously untitled paintings.

Kim Conaty, curator of drawings and prints at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, where she is currently working on a major Hopper exhibition, tells the Times that Shadwick’s research “cuts straight through the widely held perception of Hopper as an American original.”

She adds that the new paper will likely serve as “a pin in a much broader argument about how to look at Hopper.”

Part of what makes the discovery so newsworthy is that Hopper was “notoriously arrogant,” says artist Kristina Burns, who used to have a studio at the Edward Hopper House, to the Rockland/Westchester Journal News’ Jim Beckerman. Once, he reportedly claimed, “The only real influence I’ve ever had was myself.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/f0/0cf03312-db71-44f6-8a27-f2a7fbeafb0b/gettyimages-514079784.jpg)

Shadwick, who is halfway done with his PhD program, is currently at work on a thesis that studies the notion of “Americanness” in Hopper’s paintings, he tells the Times.

Burns, for her part, says the find “doesn’t change for me that [Hopper] was the first person to synthesize what America looks like.”

In a statement posted on the Edward Hopper House Museum and Study Center’s website, Juliana Roth, the organization’s chief storyteller, says that Shadwick’s find, while fascinating, “does not reduce the importance of these paintings in the conversation of Hopper’s artistic journey.”

She adds, “As with many of Edward Hopper’s childhood objects, we suggest viewing these paintings as artifacts from the development of a young life. A young artist’s life.”

Roth concludes, “The myth of artistic genius is just that, a myth. No artist develops in a bubble, without influence, resource, or access. … [Y]oung Hopper copied freely and regularly, which is to say, he learned to see.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)