Songbirds That Learn to Make New Sounds Are the Best Problem-Solvers

Birds—and humans—are vocal learners, meaning they can imitate new vocalizations and use them to communicate

:focal(1024x761:1025x762)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a9/54/a9541a8c-1290-45f5-a671-d1f1f3e65cc9/blue_jay_185317371_1.jpeg)

Birds can make an array of noises, from elegant trills to ear-piercing squawks—and nearly everything in between. One reason for this wide range is their ability to imitate new vocalizations and communicate with them, a process known as vocal learning. Humans do this, too, when first developing language skills.

“Learning new sequences of sounds helps to successfully communicate with others and is often useful when you’re going to meet new members of your species that you haven’t met before,” Michael Goldstein, a psychologist at Cornell University who was not involved in the study, says to Popular Science’s Jocelyn Solis-Moreira.

But researchers have long wondered whether the bird species with the best vocal learning skills are also the most intelligent. Now, they’ve found a link between avian vocal learning and a key part of intelligence: problem-solving.

Songbirds with the most complex vocal learning capabilities were also the best at solving problems during experiments, according to a new paper published last week in the journal Science. These high-achieving vocal learners also had the biggest brains compared to their body size, the team finds.

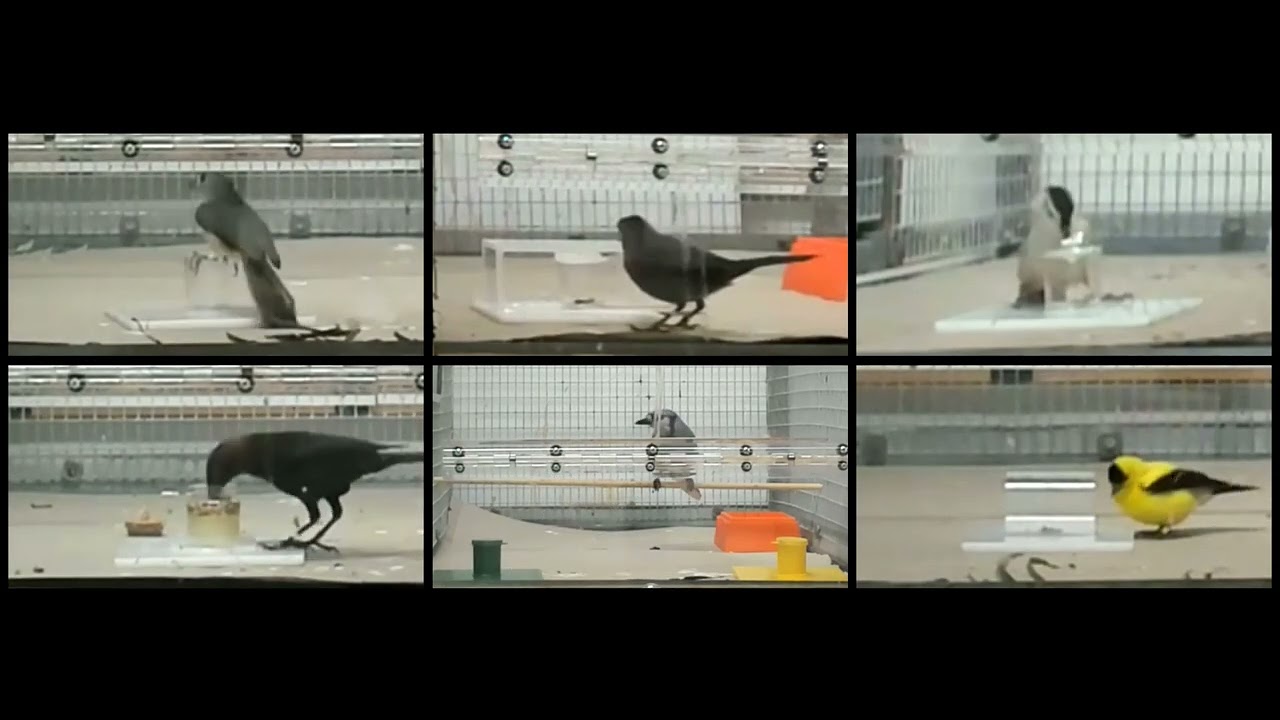

Past research on this subject focused primarily on individual species—and produced murky results. So, researchers decided to view the question through a wider lens by comparing 214 individual songbirds representing 23 different species.

They ran the birds through tests designed to measure various cognitive abilities, such as problem-solving, self-control and associative learning, which involves linking two unrelated things together (like how Ivan Pavlov famously taught dogs to associate the sound of a bell with an impending tasty morsel).

The birds’ problem-solving tasks included things like removing a lid or piercing a piece of foil to retrieve a treat, while the self-control test involved navigating around a transparent barrier—rather than butting up against it—to reach food. The researchers also taught the birds to associate a certain color with a snack, then switched the colors and recorded how long it took the birds to adapt.

Scientists compared each species’ performance on the tasks with their vocal learning prowess. Three species—starlings, blue jays and gray catbirds—had emerged as the most adept vocal learners, according to a statement. They made a wide variety of vocalizations and were the only species in the study that could mimic other birds.

After analyzing the data, the researchers found that these three species also displayed some of the highest problem-solving prowess. And across the board, they documented a strong correlation between vocal learning and problem-solving abilities: Birds with wider vocal repertoires, those that displayed lifelong vocal learning and species that could mimic other birds were associated with better problem-solving skills. The tufted titmouse, for example, which makes some 63 vocalizations and learns them throughout its life, performed problem-solving tasks more quickly than the brown-headed cowbird, which learns about nine vocalizations during one specific period, writes Science News’ Darren Incorvaia.

By contrast, however, vocal learning did not appear to be linked to the other cognitive abilities measured, such as self-control and associative learning.

The findings suggest that vocal learning, problem-solving and brain size may have evolved together. Still, these skillsets rely on different regions of the brain. Perhaps, the researchers say, something unknown connects these areas.

“Our next step is to look at the brains of the most complex species and try to understand why they are better at problem-solving and vocal learning,” says study co-author Jean-Nicolas Audet, a biologist at Rockefeller University, in the statement. This may also help them understand the genetic underpinnings between the two traits.

If a genetic link between vocal learning and problem-solving does exist, that could provide useful insights for researchers studying how spoken language evolved in humans.

“There is a chance that we will discover genes related to problem-solving and vocal learning that are possibly also used in humans for those same behaviors,” Audet tells Science News.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)