You Could Own a Lipstick Gun, a Poison-Tipped Umbrella and Other KGB Spy Tools

Next February, Julien’s Auctions will sell some 3,000 items from the shuttered KGB Espionage Museum’s collection

:focal(934x540:935x541)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/aa/ddaa0765-819f-4f68-a0f2-1de780711dcf/326671800.jpg)

It’s no surprise that lipstick is more commonly associated with beauty than death. The tiny tubes are typically unassuming, ordinary objects found bouncing around in purses or forgotten in desk drawers. Perhaps that’s why the KGB—the Soviet Union’s secret police force—created a single-shot lipstick gun for female spies to use on their targets: A weapon both deadly and alluring, it delivered a literal “kiss of death.”

Come next year, one such lipstick gun will go on sale alongside more than 3,000 Cold War espionage artifacts. Per a statement from Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills, the February 13 auction will also feature a replica of the poison-tipped umbrella likely used to assassinate Bulgarian author Georgi Markov, a 1,000-pound stone sculpture of Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, a German phone tapping device dated to World War II, a steel door from a former KGB prison hospital, and a purse with a hidden camera and shutter.

The sale is taking place under less-than-auspicious circumstances. As Sarah Bahr reports for the New York Times, all of the memorabilia comes from the KGB Espionage Museum, a for-profit institution that opened in New York City just last year. Due to financial hardship associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, the museum is permanently shutting its doors and selling off the majority of artifacts in its collection.

“The KGB Espionage Museum’s collection of Cold War era items is one of the largest and most comprehensive in the world,” Martin Nolan, executive director of Julien’s Auctions, tells the Observer’s Helen Holmes. “… We anticipate the auction will attract a wide range of collectors from museum curators to historians to James Bond fans, particularly in this election year.”

Lithuanian collector Julius Urbaitis launched the museum with his daughter, Agne Urbaityte, in January 2019. (The pair co-curated but did not own the museum, which was funded by anonymous investors, per the Times.) As Patrick Sauer reported for Smithsonian magazine in February 2019, Urbaitis started collecting artifacts related to World War II as a young man, but his interests soon shifted to KGB memorabilia. Ultimately, the 57-year-old amassed a collection of more than 3,500 items.

“When Dad gets interested in something, he wants to know everything about it,” Urbaityte told Smithsonian. “Whatever it is—motorcycles, old cars, listening devices—he figures out how it works, becomes an expert, and moves on to the next topic. He understands how [every object] works in the museum.”

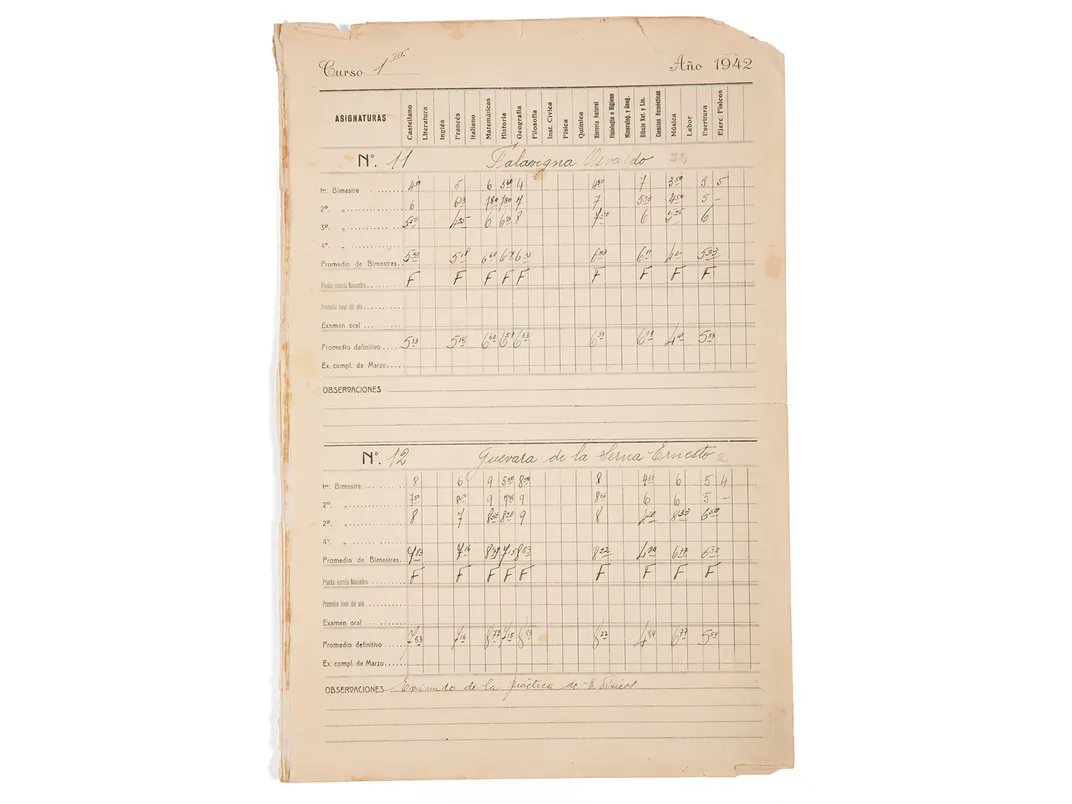

In addition to featuring ingenious devices like the lipstick gun and hidden purse camera, the museum displayed an array of miscellaneous Cold War artifacts, from Che Guevara’s high school report card to a signed letter from Fidel Castro detailing his hopes of infiltrating the Cuban capital of Havana. (Both documents, as well as other items associated with the Space Race and Cuban Revolution, are included in the upcoming sale.)

The father-daughter duo sought to create an educational experience without wading into politics: “From the first day of the museum’s operation, we have had a huge sign that we are apolitical,” Urbaitis tells the Times.

This apolitical stance—as well as the museum’s broader mission—attracted its fair share of criticism during the institution’s brief run. Writing for the New Yorker in January 2019, Masha Gessen described the museum as “a place where the K.G.B. is not only glorified and romanticized but also simply normalized.”

Short for Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti—or the Committee for State Security in English—the KGB served as the Soviet Union’s intelligence agency and secret police force from 1954 until 1991. Per History.com, KGB agents identified and often violently silenced anti-Communist or pro-religion dissidents. Methods employed included rubbing toxins on victims’ skin and stabbing targets with an umbrella that dispensed a ricin-laced pellet, as Calder Walton noted for the Washington Post in 2018.

Washington, D.C.’s International Spy Museum also took issue with the museum, albeit for different reasons: In January 2019, reported Kyle Jahner for Bloomberg Law, the former sued the KGB Espionage Museum for trademark infringement and deceptive practices. The suit was settled under undisclosed terms two months later, according to the Times.

Despite attracting ire and experiencing a major setback with the museum’s closure, Urbaitis remains passionate about KGB memorabilia. He will continue to run his similarly themed Lithuanian museum, the Atomic KGB Bunker, and tells the Times that he wants to ensure the collection ends up in good hands.

Urbaitis adds, “The exhibits will go to the museums of the world and to the hands of serious, authoritative and rich collectors.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/da/7adad79c-a26b-421a-a040-e72243175b99/326672700.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/28/2c2857d2-f7f9-49ff-a06a-7c26245974dd/326672500.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/ee/40ee2260-8855-4b1c-8ff2-0c41d4b51521/326689801.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/5c/7e5cfc32-eef4-4a5f-89d9-ecd46a483b80/7652000.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/96/1d967187-78ec-4666-83b1-8edbe4fb92e3/lenin.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)