Swiss Institute Reimagines Duchamp’s Readymades for the Modern World

The exhibition asks visitors to revisit the objects in their daily life that are often taken for granted

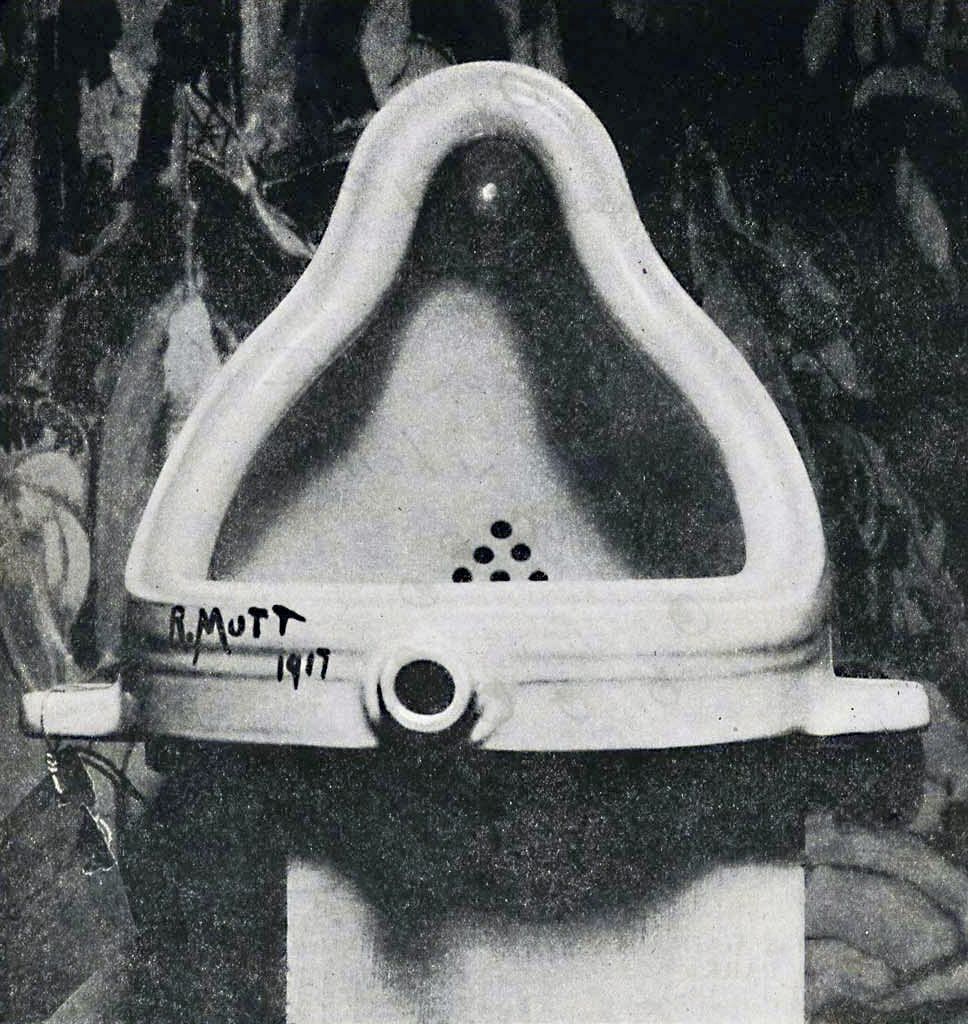

When Marcel Duchamp submitted “Fountain”—a urinal turned on its side and signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”—to the Society of Independent Artists’ Salon in 1917, he elevated the everyday into art.

By introducing the world to “readymades,” or ordinary objects reimagined as works of art, the Dada master put forth a concept that upended centuries of artistic practice by appropriating mass-produced images, critiquing the art world’s rigidity, subverting standard definitions of beauty and, ultimately, flipping the idea of what art was on its head.

It’s been some 100 years since “Fountain” first arrived on the scene. Now, Eileen Kinsella writes for artnet News, an exhibition at the non-profit Swiss Institute in New York City wants to present an updated take on the readymade, newly reimagined for the modern world.

According to a press release, the idea behind Readymades Belong to Everyone is to use the works to emphasize “issues of security, real estate and surreality and echoes everyday life in many of today’s major metropolitan areas.”

So, while Duchamp’s readymades appropriated items commonly found during the early 20th-century—for example, an iron bottle drying rack, typewriter cover and unpainted chimney ventilator—the works chosen by exhibition co-curators Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen reflect the fast pace of a globalized world.

The more than 50 pieces on view, including “Gate,” a graffiti-covered airport security walk-through gate refashioned by anonymous artist collective Reena Spaulings, and “Fire,” a billboard-sized, plywood print of a firetruck, are intended to force viewers to revisit contemporary cultural artifacts often taken for granted.

Despite differences in time period and, subsequently, the types of objects chosen as readymades, the New York Times' Joseph Giovannini argues that Duchamp and the featured contemporary artists share a talent for “rephrasing objects in distortional ways.”

To assess the validity of this statement for yourself, consider pieces like Jennifer Bolande’s “Conjunction Assemblage”—the readymade’s centerpiece, a refrigerator door topped by a black speaker frame, neatly blends into the gallery’s white walls—or Lena Tutunjian’s “The Individual (Lunch)”—an assemblage of crumpled napkins, a half-eaten Subway cookie and an empty coffee cup that looks as if it’s been carelessly left on a windowsill by a gallery staffer.

As Hyperallergic’s Zachary Small notes, these items “could pass for stage scenery and props.” Others featured in Readymades, including Alan Belcher’s “Desktop” installation of 23 ceramic JPEGs and Maria Eichborn’s “Three Paper Bags,” which features three shopping bags emblazoned with Apple’s logo, transform commercialized icons of internet culture into physical objects.

It’s easy to view readymades with a contemptuous attitude, speculating that even a child could produce similarly abstract or conceptual works. But, as artists, critics and art historians alike are quick to point out, there is more to modern art than the final product on view.

Duchamp transformed a urinal into one of the 20th century’s most influential artworks through sheer force of will; Kazimir Malevich’s "Black Square" and similarly monochrome works broke with representative painting and embraced pure abstraction. Most importantly, while it’s true that the average person could sign a urinal and call it art, no one did—until Duchamp came along. His readymades, as well as those featured in the Swiss Institute exhibition, make a case for the role timing, conception and innovation play in art.

After all, anyone can refuse to throw out the remnants of their take-out lunch, but few would have the courage—and artistic vision—to deem this trash a readymade reflection of the modern world.

Readymades Belong to Everyone is on view at the Swiss Institute in New York City through August 19. Admission is free.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)