Meet T. Rex’s Teeny Cousin Whose Name Means ‘Impending Doom’

A newly discovered tyrannosauroid provides insight into the 70 million year gap in North American tyrannosaur evolutionary records

Before Tyrannosaurus rex became the towering king of dinosaurs, its other tyrannosaur cousins were much smaller, roughly the size of a deer. The evolution of these smaller versions into T. rex is well documented in Asia, but in the North American fossil record, there’s been a 70-million-year gap in evolutionary records—until now.

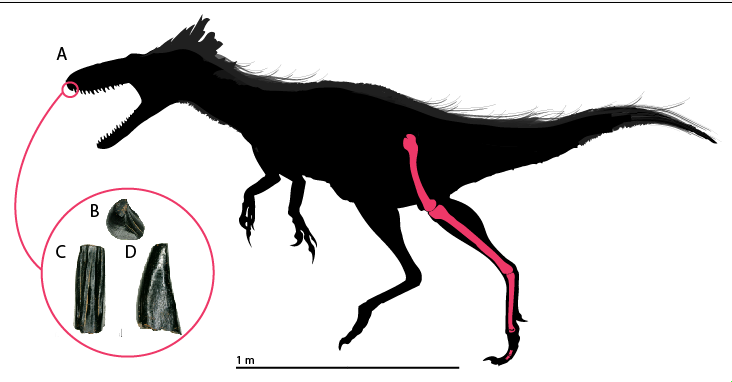

Now, fossil evidence of a new tyrannosaur species closes that gap by about 15 million years. The new species is dubbed Moros intrepidus and it roamed what is now modern-day Utah about 96 million years ago, according to a new study published in Communications Biology. This pint-size T. rex predecessor—whose name is Greek for impending doom—might just help scientists understand how tyrannosaurs eventually rose to the top of the food chain in North America.

Tyrannosaurs in the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous period would have answered to a different top predator: allosaurs. When allosaurs were top dog, tyrannosaurs would have been small-to-medium sized. During this time, however, these early tyrannosaurs were developing predatory adaptations—like speed and advanced sensory systems—that would help them easily step in as an apex predator when allosaurs disappeared by roughly 80 million years ago, according to Michael Greshko for National Geographic.

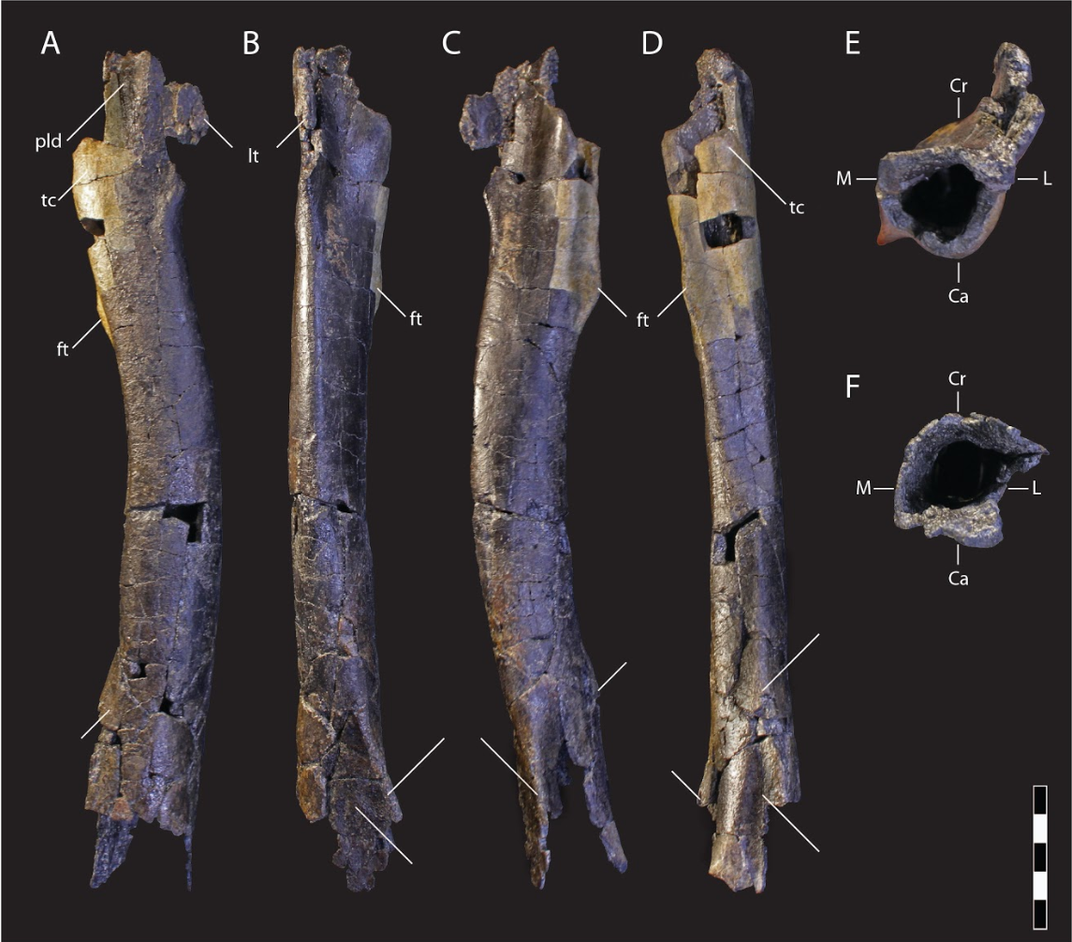

Paleontologist Lindsay Zanno of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science and North Carolina State University and her team had been scouring the rocky deserts of Utah for over a decade when they finally found a limb bone sticking out of the ground in 2012. Over the course of a few years, they carefully retrieved the bone and several others from the earth. The samples were extremely fragmented, she says, but they were able to reassemble what appeared to be a right hind leg.

By counting growth rings in the bone, they determined the specimen was at least seven years old, ruling out the possibility that Moros could have been a juvenile of a larger tyrannosaur, reports Ed Yong at The Atlantic. The unique shape of the foot and upper leg bone helped the team determine Moros was the oldest Cretaceous-era dinosaur discovered in North America.

“What I find most interesting about what Moros can teach us about tyrannosaur evolution is that we often think about tyrannosaurs as being such incredible predators, that they were destined to rule the late Cretaceous ecosystems,” Zanno tells Smithsonian.com. “But, in fact, they were living in the shadows of these archaic dinosaur lineages when they arrived here in the North American continent. And it wasn’t until those top predators went extinct, vacating those niches in the ecosystem, that tyrannosaurs were primed and ready to take over, and they did this very quickly.”

From 80 million years ago to 150 million years ago, the tyrannosaur fossil record in North America is sparse, reports Greshko for National Geographic. There are plenty small tyrannosaur skeletons from around 150 million years ago, and then gigantic remains from 80 million years ago—but a blank slate in between, reports The Atlantic’s Yong. The discovery of 96 million-year-old Moros provides evidence that tyrannosaurs were still on the continent during the mid-Cretaceous period and that tyrannosaurs were able to evolve from the size of a horse to the size of a school bus in about 16 million years.

Zanno says Moros’ long feet would have given it incredible speed, and it would have had stereoscopic vision and a highly attuned sensory system that would help its later forms dominate ecosystems. Moros differs from T. rex, though, in its size as well as its teeth.

“[Between Moros and T. rex] there were lots of intermediate [evolutionary] stages,” Hans Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Natural History, tells Smithsonian.com. “We can see that they get bigger, that their teeth get more robust. These early tyrannosaurs have blade-like teeth, but by the time you get to T. rex, it was a predator that could crush bones so it has really massive, strong teeth that kind of look like a big banana with cutting edges.”

Sues says while he’s “surprised and excited” about the new finding, he hopes to find more complete remains of these early tyrannosaurs to better understand what they looked like and determine the timeline of specific evolutionary changes.

Zanno hopes they can eventually pinpoint exactly when allosaurs died out to help determine how tyrannosaurs made such a massive jump in size a relatively short period.

“When and where and why and how [tyrannosaurs] ascended to these top predator roles in North America has remained a mystery,” Zanno says. “We just haven’t had the fossils to answer that question. There’s still an enormous gap and discoveries that need to be made.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jane.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jane.png)