Tate Acquires Archive of Works by Little-Known Surrealist Ithell Colquhoun

The collection, featuring some 5,000 sketches, drawings and commercial artworks, promises to instigate a ‘re-evaluation of her whole career’

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/c9/f2c9721c-4484-4098-9290-7cd35cea6016/ithell_colquhoun_scylla_002_copy.jpg)

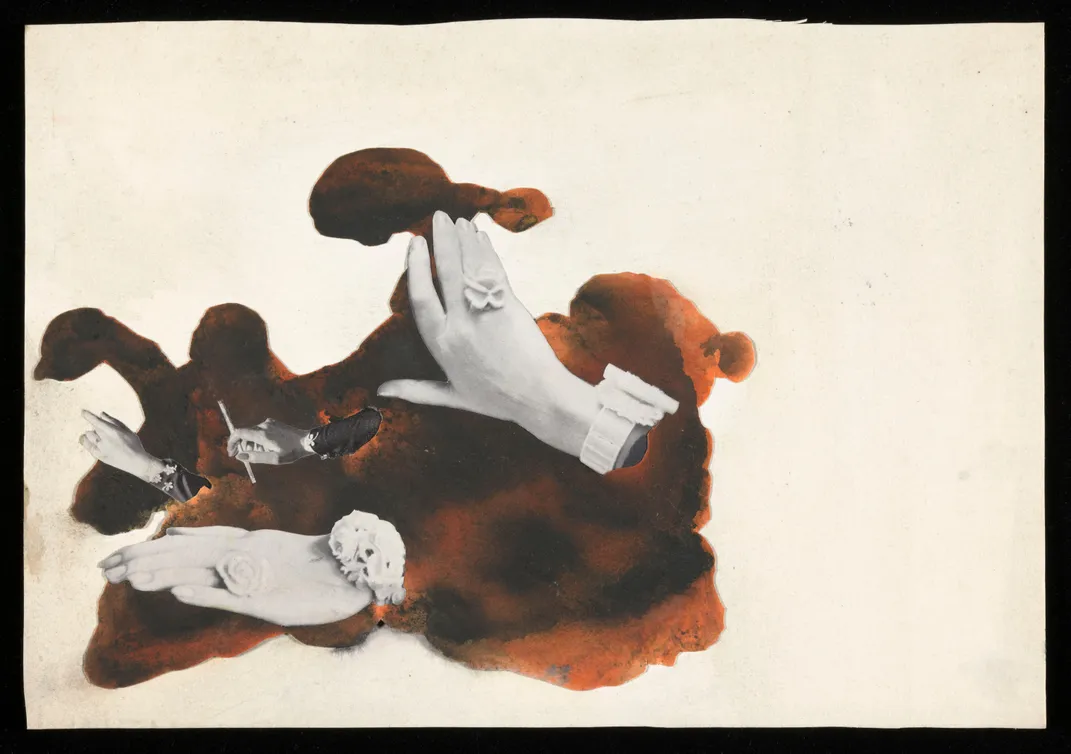

To bring her surrealist works to life, British artist Ithell Colquhoun employed techniques ranging from fumage to decalcomania, entopic graphomania and parsemage. The first uses smoke from a lighted candle to create impressions on paint, while the last finds charcoal or chalk dust scattered across a watery surface and skimmed off with a stiff piece of paper. Many of these approaches are represented in an archive of Colquhoun’s work newly acquired by Tate.

As the cultural institution announced this week, the U.K. National Trust recently gifted Tate some 5,000 sketches, drawings and commercial artworks dating to between the 1930s and ’80s. Tate already holds a significant collection of writing and art related to Colquhoun’s occult work, but this donation marks the first time the gallery’s extant holdings have been reunited with items bequeathed to the National Trust upon the artist’s death in 1988. Per the Guardian’s Mark Brown, the Colquhoun behest represents the largest single-artist collection in Tate’s archives.

According to a press release, gifted works include ink and graphite drawings, some coated with gouache or watercolor wash; architectural sketches; portraits; prints; abstract creations; and paintings reflecting the surrealist’s fascination with magic, myth and the occult. Among the other items on offer are the results of Colquhoun’s experiments with surrealist automatism, in which the artist suppresses conscious thought, and illustrations for poetic sequences she penned.

A particular highlight is a preliminary sketch for “Scylla,” a 1938 oil painting on display at Tate Britain in London. As the non-profit Art Story Foundation states on its website, the work is Colquhoun’s most “seminal,” providing a surrealist take on the narrow waterway stalked by a nymph-turned-sea monster in Homer’s Odyssey. “Scylla” is simultaneously a portrait of sorts: Take a second look at the painting, and the towering cliffs overlooking the sea reveal themselves as a pair of legs. In the artist’s own words, “It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath. … It is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image.”

Tate’s online biography of Colquhoun states that she was born the daughter of an English civil servant on duty in Colonial India in 1906. She returned to England as a child and studied at the Slade School of Art, producing figurative paintings inspired by classical mythology and the Bible. During the 1930s, Colquhoun traveled throughout Europe, spending time in Paris and Greece while mingling with the likes of André Breton and Salvador Dalí. She joined the British surrealist movement in 1939, but the relationship would be a short one: As Brown notes for the Guardian, the artist’s interest in the occult created tension with her peers, and she left the group the following year.

Colquhoun soon became a prolific author, publishing articles, poems, travelogues and novels. She continued to paint in the surrealist style of automatism and further pursued her passion for the occult, eventually becoming a priestess of Isis, a master mason and a deaconess of the ancient Celtic Church.

As the Tate press release notes, the newly acquired collection will be checked and re-housed by conservators, then catalogued and stored in the gallery’s archives. Researchers will be free to consult selected items from the archive beginning later this year.

Despite the breadth and depth of her body of work, Colquhoun remains little-known today.

“She had very few solo exhibitions,” Tate archivist Adrian Glew tells Brown. “… That’s why this collection is so amazing—it is going to be a re-evaluation of her whole career.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)