A High Schooler Discovered Thousands of Golf Balls Polluting California’s Coastal Waters

She is now the co-author of a study that seeks to quantify this underreported problem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/83/4a833b37-80a4-43ac-9c4e-8e9448d1ad0e/file-20190117-24607-6va8s.jpeg)

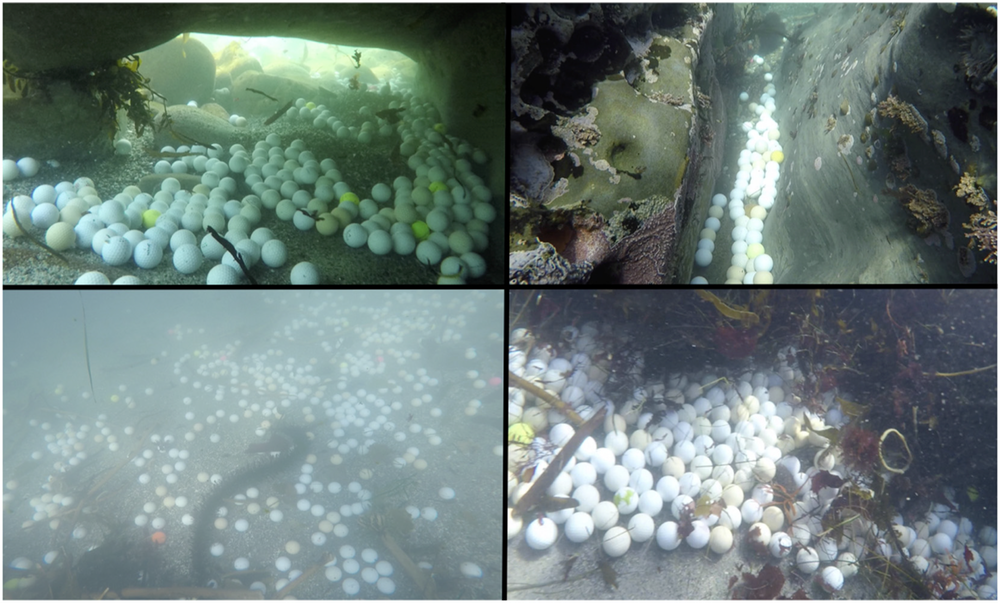

In 2017, a teenage diver named Alex Weber was exploring a small cove off the coast of Pebble Beach, California when she came across a shocking sight. The sandy floor of the cove was blanketed with golf balls. Thousands of them.

“It felt like a shot to the heart,” Weber tells Christopher Joyce of NPR.

For months, Weber and her father tried to rid the area of the small plastic balls that had settled beneath the waves. But each time they returned, more balls had been whacked into the ocean from golf courses along the shore.

When she had amassed 10,000 golf balls, Weber reached out to Matt Savoca, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University who studies human impacts on marine ecosystems. Weber and Savocas subsequently teamed up to write a paper, published recently in Marine Pollution Bulletin, that seeks to quantify the extent to which golf balls are polluting ocean environments. This issue, according to the study authors, is “likely an underreported problem associated with coastal courses worldwide.”

Savoca joined Weber, her father and her friends in their mission to haul golf balls out of the sea. At Weber’s encouragement, Pebble Beach employees also joined in the clean-up effort. The rag tag team focused on waters adjacent to two oceanside golf courses and three courses located near the mouth of the river that flows through Carmel Valley. Over the course of two years, they collected a staggering amount of golf balls—50,681, to be precise.

Because golf balls sink, they have gone largely unnoticed beneath the surface of the ocean. But these hidden pose a grave threat. As Savoca writes in the Conversation, the hard shells of golf balls are made from a coating called polyurethane elastomer. Their cores are comprised of synthetic rubber and additives like zinc oxide and zinc acrylate—compounds that are known to be highly toxic to marine organisms.

“[A]s the balls degrade and fragment at sea, they may leach chemicals and microplastics into the water or sediments,” Savoca explains. “Moreover, if the balls break into small fragments, fish, birds or other animals could ingest them.”

Most of the golf balls that the team found showed only light wear, caused by wave and tidal activity. But some of the balls had severely degraded, to the point that their cores were exposed. “We estimated that over 60 pounds of irrecoverable microplastic had been shed from the balls we collected,” Savoca writes.

And the new study focused on a relatively limited stretch of coastline. The number of coastal and riverside golf courses worldwide is not known, but according to the study authors, there are 34,011 eighteen-hole golf courses worldwide, and at least some of them are bound to pose risks to marine environments.

“With a global population of 60 million regular golfers (defined as playing at least one round per year), and a likely average of nearly 400 million rounds played per year ... the scale of this issue quickly magnifies,” the authors write.

Fortunately, steps can be taken to mitigate the problem. The researchers presented their findings to managers of golf courses along Pebble Beach, who are now working with the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary to develop strategies for getting stray balls out of the ocean before they erode. Weber is also collaborating with the sanctuary to develop cleaning procedures, and she and a friend have started a non-profit dedicated to the cause.

“If a high school student can accomplish this much through relentless hard work and dedication,” Savoca writes, “ anyone can.”