In the last years of his life, German sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt created a series of busts depicting a wide range of emotions, from petulance (see The Vexed Man) to amusement (An Intentional Wag) to shame (A Hypocrite and a Slanderer). Cast in tin alloy or alabaster, the life-size Character Heads are striking to behold, their expressions as exaggerated as the titles bestowed upon them after their maker’s death in 1783: The Incapable Bassoonist, Just Rescued From Drowning, Afflicted With Constipation.

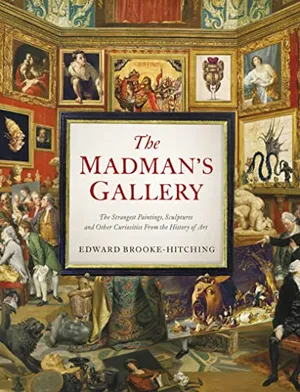

Interpreted alternatively as talismans to ward off evil spirits, manifestations of a mental illness like schizophrenia, and representations of a lost link between facial expressions and different parts of the body, Messerschmidt’s sculptures are among the 100 works highlighted in Edward Brooke-Hitching’s The Madman’s Gallery: The Strangest Paintings, Sculptures and Other Curiosities From the History of Art. Available now from Chronicle Books, this richly illustrated volume offers an “alternative guided tour of art history, focusing … on the oddities, the forgotten, the freakish, all with stories that offer glimpses of the lives of their creators and their eras,” per the introduction.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/a1/65a1abaf-d143-41e5-ae21-9f74427b4ebd/fdafsadf.jpg)

A writer and rare book collector based in London, Brooke-Hitching specializes in drawing readers’ attention to the unusual, from literary curiosities to dangerous sports to mysterious maps. As he tells Antiques and the Arts Weekly’s Z.G. Burnett, “I take a favorite fact or story from history that isn’t well known and think, ‘If this was in a book, what would the book be about?’ This way, odd material dictates an odd concept and fortunately, more often than not, the result is an original idea that offers readers new things to discover.”

Consider, for instance, a second-century marble statue of the god Glycon. Discovered beneath a railway station in Romania in 1962, the “curious and confusing” carving’s story “involves a con artist, a snake deity and a hand puppet,” writes Brooke-Hitching.

Supposedly the serpent form of healing god Asclepius, Glycon was the creation of Greek grifter Alexander of Abonoteichus. Proclaiming himself Glycon’s prophet, Alexander carried around a snake-shaped puppet with a mouth that “would open and close … by means of horsehairs” and a “forked black tongue also controlled by horsehairs, [which] would dart out,” according to Syrian writer Lucian of Samosata. The sculpture shows the serpent god with humanoid facial features and long, tousled hair.

The Madman's Gallery: The Strangest Paintings, Sculptures and Other Curiosities from the History of Art

Discover an extraordinary, illustrated exhibition of the greatest curiosities from the global history of art

Brooke-Hitching came up with the idea for The Madman’s Gallery in 2015, “a particularly strong year of comparable artistic oddness,” he notes in the introduction. The author cites Banksy’s dark take on Disneyland (Dismaland Bemusement Park) and performance artist Stelarc’s decision to grow a third ear and attach it to his arm as chief examples of this trend.

The Madman’s Gallery has much in common with Brooke-Hitching’s previous book, The Madman’s Library, which focuses on unusual written works rather than art.

Speaking with Smithsonian magazine in 2021, the author said, “Just taking this idea of strange books, it actually leads you around the world into different cultures. You realize everyone has their own form of curiosities, and that as a species, we’ve always been incredibly strange and weird, but also very funny and endlessly imaginative.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/20/79/2079a18b-06f8-4902-a1ff-20bca64b9cb1/glycon_51644816839.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/39/67395229-a81a-4904-af55-ee1e35eed0de/face.jpg)

Brooke-Hitching’s new project has a similar ethos, traversing the globe in its exploration of artistic curiosities. In Japan, the author details kusozu, watercolors depicting the nine stages of human decomposition, which “were used to highlight the impermanence and foul nature of the mortal body,” as well as discourage lust among Buddhist monks and devotees.

In Russia, he highlights dog-headed icons of Saint Christopher—a reflection of the “widely held medieval belief in a foreign race of dog-headed men living somewhere at the edge of the world.” And in Peru, he revisits 17th-century portraits of the ángeles arcabuceros, or angel musketeers. Dressed in a mixture of pre-Columbian and Spanish clothing, these winged, armed angels combine local legends of “deities of the stars” with “the imperial magnificence of Christianity.”

Some of the works included in the book are more recognizable than others. After all, no compendium of enigmatic art would be complete without mention of Hieronymus Bosch’s visions of heaven and hell or Salvador Dalí’s Surrealist creations. But perhaps the most surprising entry is one that offers a fresh take on the world’s most recognizable painting: the Mona Lisa.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/bf/d1bf7af9-706c-4292-8d91-9fcf2f89413a/1920px-kusozu_the_death_of_a_noble_lady_and_the_decay_of_her_body_wellcome_l0070295.jpg)

As Brooke-Hitching points out, the portrait hanging in the Louvre isn’t the only Mona Lisa. The Prado Museum in Madrid houses a version thought to be painted by a member of Leonardo’s workshop at the same time as its more famous counterpart. The work portrays its subject from a slightly different perspective, yet it mirrors every pentimento, or change, seen in Leonardo’s original.

“This suggests it was painted simultaneously by one of Leonardo’s students—quite possibly by Salaì—at the neighboring canvas,” the book notes.

Salaì, an apprentice described by Leonardo as a “thief, liar, obstinate, glutton,” also painted a nude version of the Mona Lisa known as the Mona Vanna. One of around 20 similar depictions, the work’s existence has sparked speculation that Leonardo himself painted a nude Mona Lisa, now thought to be lost. Some scholars think a charcoal drawing housed at the Condé Museum in Chantilly, France, is a preparatory work for this missing painting.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/30/ac/30ac965f-7672-474a-a59b-6e01fc0ebf1c/estudio_de_desnudo_para_la_gioconda.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/02/ec/02ec6a44-3125-4ed8-b615-8defd255c350/mona.jpg)

“It’s possible, though there’s no certainty, that this was the preparatory drawing for the painted Joconde Nue,” curator Mathieu Deldicque told the London Times’ Charles Bremner in 2017. “We don’t even know if that portrait was really painted but there’s a strong probability that it was. What has tipped us off are retouches. There are little clues. … The creative work on this oeuvre is very close to the lower part of the Mona Lisa, the one in the Louvre.”

Ultimately, writes Brooke-Hitching, his imagined gallery is one of “stolen art, outsider art, art made to be destroyed and art made from people, scandalous and satirical art, art of the heart and the art of men in flames.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/a4/01a4baeb-b23b-4383-a6d8-82024c8daeb6/540px-gioconda_copia_del_museo_del_prado_restaurada.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5d/e5/5de56264-a578-475d-819f-eca725531b22/head.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/05/c705207c-8836-47de-874d-fb8f8ee7ab46/untitled-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a3/d3/a3d3dccf-b529-4d93-8015-796e66153202/christopher.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/a2/baa2728d-77e3-40bc-992e-976449b6d992/man-in-flames.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8a/31/8a311e52-90ec-421c-a16d-8dc15f487f1c/2560px-smithsonian-hamilton-throne-2039.jpeg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/87/fe/87fe10e5-8e49-45ab-9bc8-d273530ff96f/weird-art.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)