The Unheralded Women Scribes Who Brought Medieval Manuscripts to Life

A new book by scholar Mary Wellesley spotlights the anonymous artisans behind Europe’s richly illuminated volumes

:focal(640x373:641x374)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d0/5a/d05ad97d-62c7-4a3e-825b-a300d7e3d1e7/marie.jpg)

At first glance, the writer of an eighth-century biography of Saints Willibald and Winnebald offers few clues regarding her identity, describing herself only as an “unworthy Saxon woman.” Upon closer inspection, however, a seemingly meaningless series of lines inserted between two blocks of text reveals a decisive declaration of authorship. Decoded by scholar Bernhard Bischoff in 1931, the hidden message reads, “I, a Saxon nun named Hugeburc, composed this.”

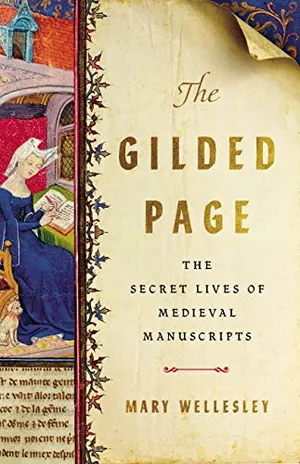

Penned at a time when “many different hands”—most of them anonymous—contributed to the creation of each individual manuscript, Hugeburc’s words are “something of an exception,” writes historian Mary Wellesley in her new book, The Gilded Page: The Secret Lives of Medieval Manuscripts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ca/87/ca87c082-a48e-4b5d-a2c5-d931ad354f09/1280px-ms_clm_1086_-_f71v.jpg)

“I like to think she stitched this code into the space between the texts because she had some inkling of the way authors’ names were often lost in manuscript transmission,” Wellesley adds. “When manuscripts were copied and recopied, there was no guarantee that an author’s name would survive the process, especially if that name was a female name.”

Out now from Basic Books, The Gilded Page resurfaces the stories of Hugeburc and countless individuals like her, tracing the intricate process of translating text into beautifully illuminated manuscripts while celebrating the unheralded achievements of their creators—particularly women. As Boyd Tonkin notes in the Arts Desk’s review of the book, “Manufacture of lavish manuscripts could take almost as long as building the abbeys and cathedrals that housed them.”

The Gilded Page: The Secret Lives of Medieval Manuscripts

A breathtaking journey into the hidden history of medieval manuscripts, from the Lindisfarne Gospels to the ornate Psalter of Henry VIII

Speaking with Matt Lewis of the “Gone Medieval” podcast, Wellesley explains that the word manuscript (derived from the Latin manus, or hand, and scribere, to write) simply refers to a handwritten object, whether it be a charter, a map or a copy of a poem. Manuscripts are distinct from texts: The famed Canterbury Tales, for instance, are cobbled together from roughly 98 manuscripts of “varying degrees of completeness.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6a/44/6a44be34-f1cf-4aea-86c9-02c13c38bb63/wife-of-bath-ms.jpeg)

Prior to the 14th century or so, when paper became more widely available, manuscripts were written on animal skins known as parchment or vellum. Scribes, who were either members of the clergy or trained professionals, copied existing manuscripts or transcribed dictated accounts, copying an average of 200 lines of text per day for a total of about 20 books in a lifetime, writes Gerard DeGroot for the London Times. Though manuscripts were often richly adorned, with gold or silver gilding applied to their surface, they weren’t exclusively owned by royals and nobles. By the end of the medieval period, scholar Sandra Hindman told AbeBooks earlier this year, “‘ordinary people’ like doctors, lawyers, teachers and even merchants” could also acquire their very own volumes.

Part of what attracted Wellesley, an expert on medieval language and literature, to manuscripts was their tangible presence—a stark departure from the e-books of today. “An ancient manuscript tells secrets not only of its writer and scribe, but also of the readers who have handled it,” the Times notes. “They annotate, mutilate and steal. They leave wine stains, flowers pressed into pages and drips of candle wax.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/70/c9/70c972e4-a95a-4b58-b002-94e9e2bd3522/1280px-pisan_gallica.jpeg)

Wellesley also hoped to highlight manuscripts’ status as portals into the lives of those “who aren’t always ... discussed in our medieval histories—people of a lower social status, women or people of color,” per The Gilded Page. Examples explored in the book include Margery Kempe, a middle-class woman who worked alternatively as a brewer and a horse-mill operator, overcoming illiteracy to dictate the earliest autobiography in English; Leoba, a nun who was the first named female English poet; and Marie de France, who, like Hugeburc, refused to be anonymous, instead hiding her name and country of origin in lines of verse.

Complicating Wellesley’s efforts to excavate the stories of forgotten scribes is the fact that “the vast majority of manuscripts produced in the medieval era perished through fire, flood, negligence or willful destruction.” In Tudor England, iconoclastic Protestant reformers used the “contents of monastic libraries … as candlestick wedges, kindling, for boot cleaning and [toilet] paper,” reports Roger Lewis for the Telegraph. Raging infernos destroyed many priceless manuscripts; others were recycled, their pages cut up and reused to make bindings for new books, or tucked away in European estates, only to be rediscovered by chance centuries later. (A copy of Kempe’s autobiography, for example, was found stashed in an English family’s ping-pong cupboard in 1934.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/a3/48a3d67f-c8aa-409b-b61d-c48262b3d567/henry_viiis_psalter_british_library.jpeg)

From well-known manuscripts like Henry VIII’s Book of Psalms and the Lindisfarne Gospels—created by a single “talented artist-scribe named Eadfrith” rather than the usual “team of artists and scribes,” as historian Linda Porter writes for Literary Review—to more obscure works like the Book of Nunnaminster, whose use of Latin feminine word endings suggests “it was made by or for a woman,” per Lapham’s Quarterly, The Gilded Page is a valuable addition to the wave of recent scholarship centered on publicizing hidden histories.

“One of the things I really wanted to do in the book was … mention women in every single chapter,” Wellesley tells “Gone Medieval,” “because I wanted to make clear that women were involved in the production of manuscripts at every level.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)