The Soviet Spy Who Invented the First Major Electronic Instrument

Created by a Russian engineer, the theremin has delighted and confounded audiences since 1920

:focal(854x422:855x423)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/43/5543a2cc-dfe8-44f2-ab90-135deab7d134/screen_shot_2020-12-02_at_11654_pm.png)

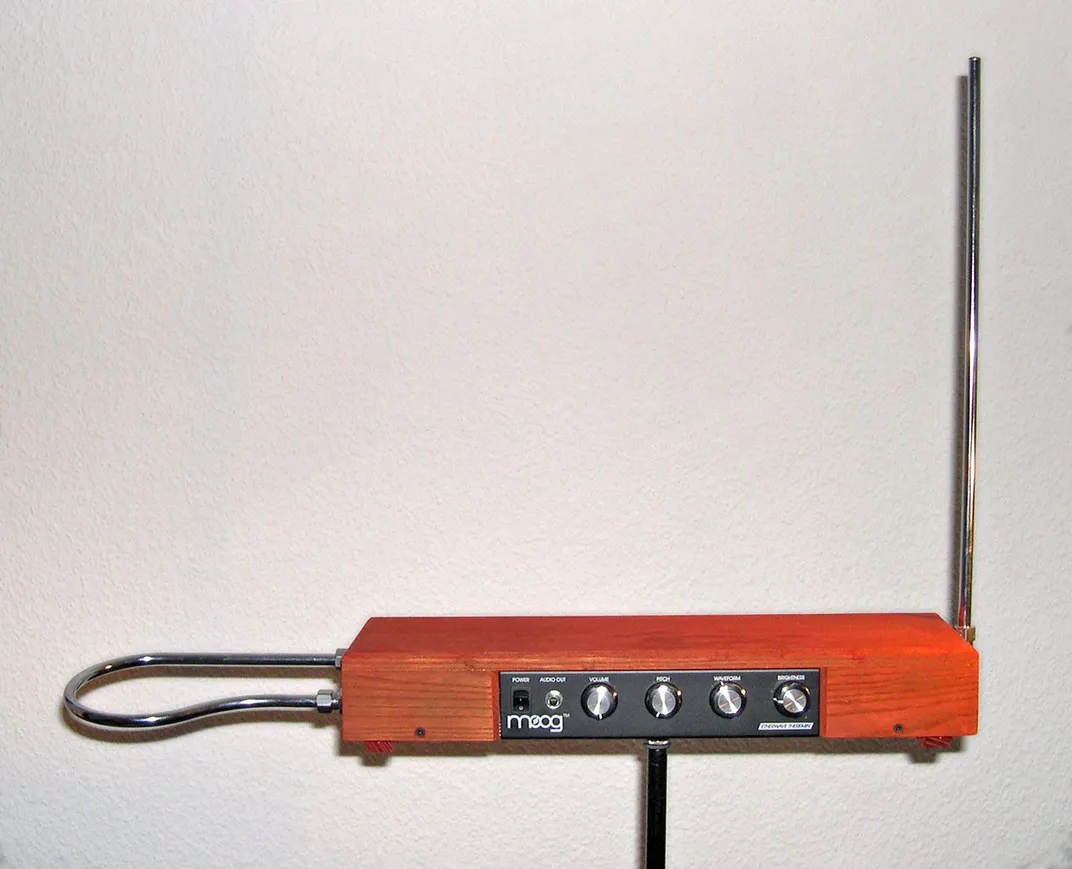

In the early 1920s, Soviet radio engineer León Theremin shocked audiences around the world with what appeared, at first glance, to be a magic trick. Standing in front of a contraption resembling a radio with two antennas, he conducted his hands in precise patterns and shapes, never touching the device itself. As Theremin’s hands moved, an eerie mechanical harmony issued forth, as if he were pulling the music out of thin air.

One hundred years later, Theremin’s namesake instrument continues to astound and inspire. In honor of its centennial, musicians, inventors and musicology enthusiasts alike are celebrating the history—and enduring intrigue—of the unusual instrument.

“When you play the theremin, it looks kind of magical. Maybe even as if you could cast spells,” Carolina Eyck, one of the few expert theremin players active today, tells BBC Culture’s Norman Miller. “No other instrument is played without physical contact. You are part of the instrument, conducting the air.”

Theremin accidentally invented the device in 1920, as David A. Taylor reported for Smithsonian magazine last year. A physicist and trained cellist, he was developing proximity sensors that used sound waves to sense approaching objects when he realized he could manipulate sound waves between two antennas to create something evocative of an alien, warbling violin—“like a human voice in falsetto, pinched through a straw,” writes Matthew Taub for Atlas Obscura.

To manipulate Theremin’s original design, which he officially patented in 1928, users move their hands next to two wires jutting from a small box, manipulating the electromagnetic fields between the antennas. By moving one’s fingers up or down, the player is able to raise or lower the music’s tone.

After refining his technique, Theremin began to perform to wide acclaim. Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin was so impressed by a 1922 demonstration, in fact, that he sent the inventor on a tour of Russia, Europe and the United States to share his modern, Soviet sound with the world (and surreptitiously engage in industrial espionage). Beginning in December 1927, Theremin toured the U.S. extensively, making stops at the New York Philharmonic, Carnegie Hall and other major venues.

When Theremin returned to his home country in 1938, however, he didn’t exactly receive a hero’s welcome: The communist regime sent the engineer to a Soviet work camp where he was forced to create spyware, including bugging tools and listening devices, writes Albert Glinksy, composer and author of Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage, in a blog post for instrument manufacturing company Moog.

Over the following decades, Theremin’s invention garnered a dedicated fanbase and sold for about $175 per instrument (roughly $2,600 today).

“It was the first successful electronic instrument,” Jayson Dobney, a musical instruments curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, told Smithsonian last year.

Russian émigré Clara Rockmore became the instrument’s best-known virtuosa by developing her own unique technique, writes Glinksy in a separate blog post.

“In many ways, we have Clara to thank for legitimizing the theremin,” Glinksy writes. “In the 1930s and ’40s it was she who proved that it was more than just a gadget.”

The electro-theremin, a descendant of Theremin’s original device, was featured in the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.” And musician Samuel Hoffman used the instrument to craft the otherworldly score of science-fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951).

Theremin’s device also inspired Robert Moog, an American inventor who built his own theremin at age 14 by copying drawings found in a hobbyist magazine, per Smithsonian. Moog would go on to change the music landscape forever when he debuted the first commercial modern synthesizer in 1964.

In honor of the theremin’s centennial, the Moog manufacturing company has designed a limited edition theremin dubbed the “Claravox Centennial” after Rockmore herself, reports Kait Sanchez for the Verge. Music lovers can listen to thereminist Grégoire Blanc and pianist Orane Donnadieu demonstrate the instrument in a rendition of “Claire de Lune,” available on YouTube and Soundcloud.

“No matter how sophisticated our synths and samplers,” writes Glinsky, “our sequencers or audio workstations, seeing someone’s hands glide and bounce through the air around the theremin’s antennas, even after a century has passed, still leaves us delightfully open-mouthed.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)