There’s a New Breed of Botulism, And We Don’t Have a Cure for It

It’s new, it’s deadly, and it fights off our best anti-toxins

In a fecal bacterial sample drawn from a baby sick with botulism, researchers in California discovered something unnerving: a new strain of botulinum toxin. This is the first new strain of the toxin found in more than forty years, and the discovery, says microbiologist David Relman in an editorial that accompanied the research describing the new toxin, poses a serious health risk.

This new toxin, BoNT/H, cannot be neutralized by any of the currently available antibotulinum antisera, which means that we have no effective treatment for this form of botulism. Until anti-BoNT/H antitoxin can be created, shown to be effective, and deployed, both the strain itself and the sequence of this toxin (with which recombinant protein can be easily made) pose serious risks to public health because of the unusually severe, widespread harm that could result from misuse of either.

One of the downsides of the advanced techniques of modern medicine is that the tools usually used for drug design can also be used to make deadly bioweapons. As Relman said, if people knew the exact composition of the toxin it wouldn’t be hard at all to make it. NPR:

Biology has long had a tradition of openness, to allow people to confirm research findings and build upon others’ discoveries. But some worry that new technologies have made it easier for basic science to be exploited by people with evil intentions.

And any expert in botulinum toxin knows that its history as a possible bioweapon goes back decades. The Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo even tried to release it in downtown Tokyo in the 1990s, but these attacks failed.

One scholarly article on the toxin noted that a single gram could potentially kill more than a million people, if it was evenly dispersed through the air and inhaled — although that would be difficult to do.

Because of that danger, says NPR, the whole thing is being kept rather hush-hush. The scientists aren’t releasing the details on the toxin until a anti-toxin can be found.

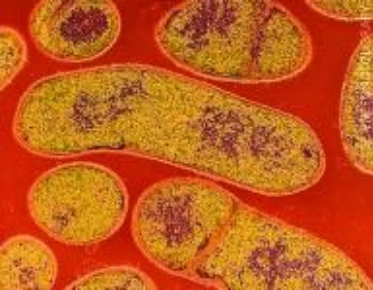

The bacteria Clostridium botulinum. Photo: CDC

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)