These Beautiful 16th Century Watercolors Illustrate the History of Comets And Meteors

Today, studying comets and meteors involves billions of dollars worth of equipment and teams from all over the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201309090900269665887678_06cd24e100_z.jpg)

Rod MacKinnon, a Nobel Prize-winning biochemist at Rockefeller University, was at New York’s Brookhaven National Laboratory studying the structures of human proteins, when his and Steve Miller’s worlds collided. Miller, an artist who splits his time between New York City and the Hamptons, was visiting Brookhaven to better understand the types of advanced imaging that scientists use.

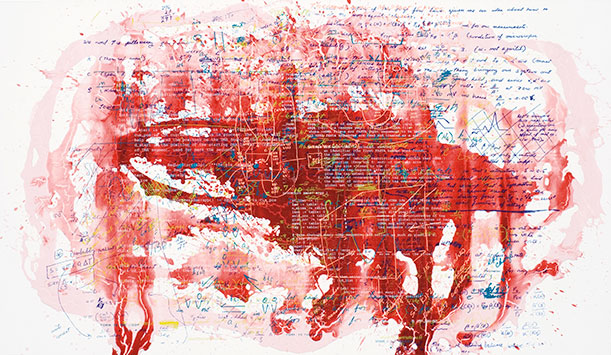

Evolutionary Tango, by Steve Miller.

The meeting inspired Miller to incorporate some of MacKinnon’s scientific notes and computer models into a series of paintings. It seemed logical to him to combine the creative output of an artist and a scientist. ”We’re all asking questions, trying to understand what forces make or shape who we are,” says Miller.

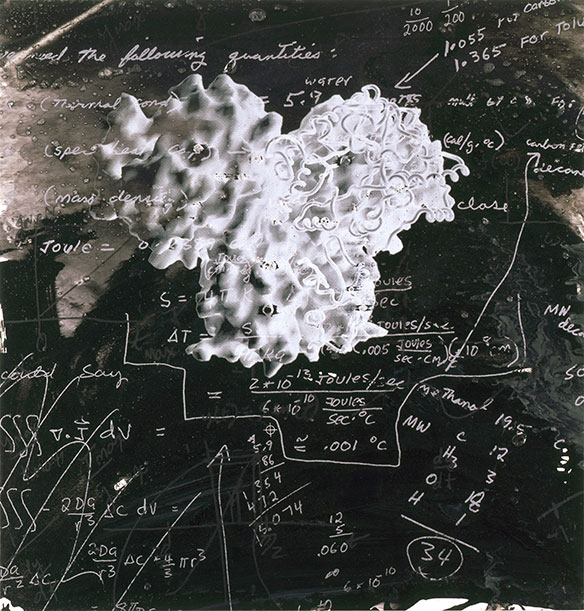

Blackboard Jungle, by Steve Miller.

The pair had a similar interest, according to Marvin Heiferman, curator of an exhibition of 11 of Miller’s paintings now at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. “MacKinnon was investigating how potassium ions moved across cell membranes. Miller’s work engages itself with the crossing of borders as well: moving back and forth between photography and painting, shifting from micro to macro scale, combining representational and abstract imagery and what is theorized with what can be seen,” writes Heiferman in an introduction to the exhibition, aptly named “Crossing the Line.”

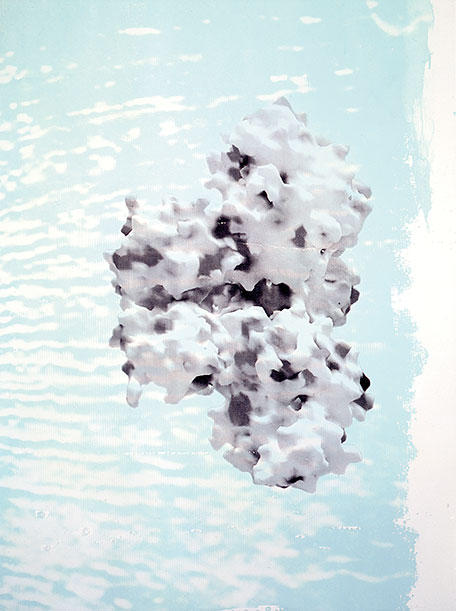

Flight School, by Steve Miller.

A large part of Miller’s career has been devoted to walking this line, between art and science. He has created abstract Rorschach-looking paintings from images of cancer and blood cells that only a scientist would recognize as such, and his “Health of the Planet” series consists of x-rays of plants and animals living in the Amazon rainforest.

Booming Demand, by Steve Miller.

So, what was it about MacKinnon’s research that transfixed the artist?

“Miller became fascinated with the visual nature, vocabulary, and tools of MacKinnon’s work: the graphic quality of his calculations and diagrams, the computer modeling he experimented with to grasp the three dimensionality of proteins, and X-ray crystallography technology itself,” writes Heiferman.

Roam Free, by Steve Miller.

With these elements at his disposal, Miller produced paintings by layering photographs, drawings, silk-screened images and script written in MacKinnon’s hand. The works are pleasing at first glance, but because of their layers, they beg a deeper look. What do the underlying calculations prove? What do the graphs with asymptotic curves represent? And, what exactly is that sponge-like blob?

Factory, by Steve Miller.

The paintings do not provide answers to these questions, but, in this way, they embody the artistic and scientific pursuit. The fun is in the scribblings and musings that happen on the way to the answer.

“Crossing the Line: Paintings by Steve Miller” is on display at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. through January 13, 2014.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)