Photographer’s Innovative Pictures Captured Lesser-Seen Faces of Jim Crow South

Hugh Mangum’s portraits reveal his subjects’ array of emotions and defy stereotypical snapshots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/5b/d25b982d-d253-468e-a457-9176e63b2861/screen_shot_2019-01-17_at_22752_pm.png)

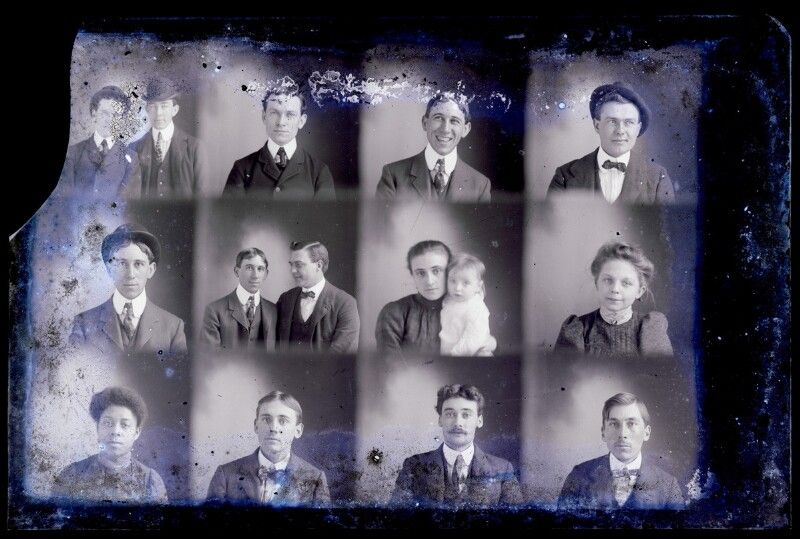

Hugh Mangum’s subjects appear somewhat stilted at first glance, their natural energy undercut by the anesthetizing gaze of the camera lens. But as the frames progress, the photographs lose the statuesque quality common amongst early studio portraits of unsmiling men and women, instead capturing moments of joy, surprise and, most impressively, spontaneous fun.

It’s this singular quality that drew photojournalist Sarah Stacke’s attention when she first flipped through a set of Mangum’s snapshots in 2010. As Stacke recounts for NPR, the “smiles and laughter,” “quirky gestures” and general playfulness of the early 20th-century North Carolinian photographer’s portraits are unique for an era often defined by its staid formality—as are the people depicted in his photographs, which include individuals of different class, gender and race living during the height of Jim Crow.

Now, nearly 100 years after Mangum’s death in 1922, his work is finally being seen by a wider audience.

Photos Day or Night: The Archive of Hugh Mangum, a new monograph edited by Stacke and curated in conjunction with the photographer’s granddaughter, Martha R. Sumler, draws on unseen images and ephemera from the family’s archive, offering an unusually vibrant portrait of both the man behind the camera and the subjects in front of it.

As the self-portraits Stacke features on the volume’s title page attest—Mangum is alternately depicted in serious thought and playful costumes accentuated by such props as a parasol—life in the early 20th-century wasn’t nearly as serious as most studio shots suggest. In fact, sometimes, it could even be downright fun.

One of Mangum’s most important tools for coaxing out subjects’ more whimsical sides was the Penny Picture camera, which Stacke notes was designed to produce multiple exposures (up to 35 separate images) on a single glass plate negative. The Penny Picture operated somewhat like a modern-day photo booth, with sitters posing for a progression of photographs, perhaps involving props or shifting facial expressions.

An itinerant photographer, Magnum traveled throughout North Carolina and southwest Virginia, photographing people from all walks of life. His extant portraits of African-American clients are especially unique: As Stacke writes for NPR, these men and women “present themselves as lighthearted, resolute and everything in between. They bring their children to the studio to be photographed, an ode to the hope they have for the lives their sons and daughters will live.”

It’s likely, Stacke argues, that many such sitters “were working publicly and privately to establish black agency, independence and community vitality.” Cementing their legacies in studio portraits—especially ones in which the South’s segregation laws seem somewhat distant, their boundaries erased by the integrated nature of Mangum’s photo-filled negatives—could have served as a key step in accomplishing this goal.

Reflecting on her grandfather’s legacy, Martha Sumler tells Stacke that revisiting the images made her “realize just how much he really liked people.”

She continues, “I know it was a business for him, and he worked hard, but he had to have really enjoyed it and enjoyed meeting the people ... to show the way life was back then."

Mangum’s legacy is also being explored in a new exhibition at Duke University’s Nasher Museum of Art curated by Margaret Sartor, independent curator and Duke instructor, and Alex Harris, professor of the practice at Duke, in association with the Center for Documentary Studies and with assistance from the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Titled Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897-1922, the show chronicles the diversity of Mangum’s oeuvre, from his portraits of affluent, well-known sitters to those whose identities have been forgotten today.

According to Kerry Rork of the Chronicle, Duke’s independent student newspaper, Magnum’s “progressive belief system as a photographer” may have been informed by a variety of factors, from his education—he studied at Salem College, “an all-women’s university founded with a belief in education for all regardless of race or gender”—to the time period he lived in—born at the tail end of Reconstruction, he watched Jim Crow take shape around him.

This resurgence of interest in Mangum almost didn’t happen. After Mangum died in 1922, his family stored his work in a tobacco barn on their farm. There, these thousands of glass plate negatives remained unseen for some 50 years, until the 1970s, when the barn was slated for demolition.

The photographs almost vanished forever, but luckily the tobacco barn was saved “at the last moment,” according to a university statement, preserving this important array of portraits that defy conventions of the day.

Editor’s note, January 22, 2019: This story has been updated to more clearly distinguish Sarah Stacke's book from the Duke exhibition and its catalogue.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)