This 19th-Century Politician Never Thought He’d Be Outed for Vandalizing an Egyptian Temple

Unlike a Chinese youth shamed for the markings he left on an Egyptian Temple, Luther Bradish got away guilt-free with his sneaky bid at immortality

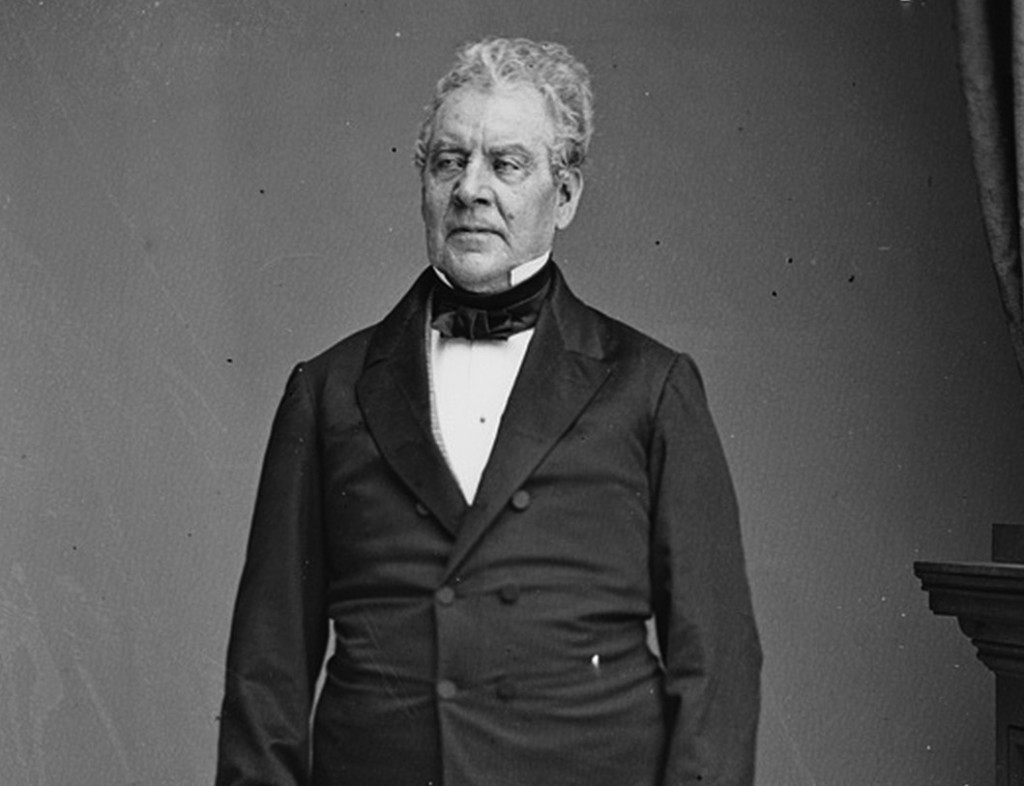

Luther Bradish, taken sometime between 1855 and 1865. Photo: Library of Congress

Visit an ancient monument like Egypt’s temples, Israel’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre or Camboia’s Angkor Wat and you’ll likely notice the plethora of hand-carved graffiti marring those priceless sites. Most of the culprits count on not getting caught. Nineteenth-century New York politician Luther Bradish, however, was not so lucky.

During a recent visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NPR’s Robert Krulwich noticed Bradish’s conspicuous moniker etched into one of the Met’s full-sized Egyptian temple. Krulwich explains the peculiar situation:

There, sitting right next to a carved Egyptian figure, an obviously important official — straight in his line of sight — was a graffito from someone named “L. Brad—” (couldn’t read the rest of it) who added “of NY US.” The date was 1821.

When nobody’s looking (I figure, even in 1821, they didn’t allow tourists to carve autographs), he does his dirty little deed and then disappears, going back, we hope, to America. His small indiscretion is a secret.

But then, the temple made its way to New York City in 1978, where, more than 100 years ago, Bradish had become something of a prominent figure.

According to a scholar named Cyril Aldred, “L. Brad—” was Luther Bradish, who served in the U.S. Army, fought in the War of 1812, became a lawyer and then became an agent — I think the modern word for it would be spy, sent by President Monroe to Constantinople, to figure out who to talk to about all the pirates chasing American ships in the Mediterranean.

Bradish, it turns out, wasn’t very good at intelligence gathering, but somewhere during his stay, he slipped down to Egypt and visited Dendur and carved his name into the limestone. Why a secret agent would do that, I don’t know.

Bradish likely never imagined he’d be called out for his vandalism by people viewing his marking in his own state, years and years after his visit to Egypt. But unlike Ding Jinhao, the Chinese youth recently shamed into apologizing for the markings he left on an Egyptian Temple, Bradish got away guilt-free with his sneaky bid at immortality.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)