Thousands of Little-Known Plant Species Are at Risk of Extinction

When researchers used machine learning to evaluate 150,000 plant species, they found that 10 percent were likely to qualify for the IUCN Red List

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/9f/079f4287-c7e8-4299-8c33-29183b314310/symphyotrichum_georgianum_georgia_aster_earlier_bloom.jpg)

When it comes to endangered species, animals like the Asian elephant, black rhinoceros and Bornean orangutan tend to draw the most attention. But a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences places the spotlight on an entirely different—but equally at-risk—kingdom of life: plants.

There are nearly 400,000 known plant species spread out across the globe, but as Gregory Barber reports for Wired, less than 10 percent have been assessed by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In total, the plants actually included on the list constitute just five percent of all known species.

Part of the problem stems from the difficulty of adding a single species to the list. In addition to requiring ample resources and specialized research, the process favors what Barber terms “charismatic” animal species over little-known plants. Add in the hefty number of identified plant species (which grows by thousands every year), as well as the geographic range of hard-to-reach habitats, and you’ll understand why plants often get the short end of the stick.

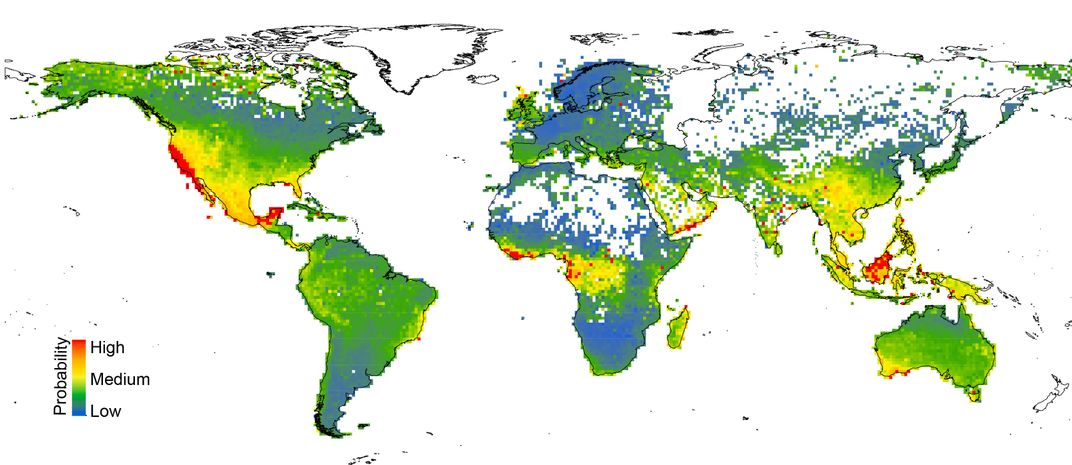

Now, a machine learning algorithm developed by scientists from Ohio State University, the University of Idaho, the University of Maryland and Virginia’s Radford University aims to speed up the risk assessment process by tracking patterns—from habitat features to weather patterns and physical characteristics—likely to place a species in danger of extinction. As Earth.com’s Chrissy Sexton writes, the team drew on open-access data from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and the TRY Plant Trait Database to evaluate more than 150,000 plant species. Of those species tested, more than 10 percent were deemed extremely likely to qualify for the Red List.

According to Europa Press, co-authors Tara Pelletier of Radford University and Anahí Espíndola of the University of Maryland trained their machine learning model by inputting GBIF and TRY data—including information on species’ range, location and traits, plus regional climate and geographic indicators—for the plants already included on the Red List. This base dataset enabled the pair to assess the accuracy of the model’s predictions by comparing them to other species’ known risk status.

In a statement, Espíndola explains that the algorithm isn’t designed to replace formal assessments using IUCN protocols. Instead, it’s designed to be a tool “that can help prioritize the process” by informing governments’ decisions on how to allocate scarce conservation resources.

The team found that some threatened species clustered in areas known for their high level of biodiversity, such as the rainforests of Central America, southwestern Australia and southeast United States. Others called more remote regions home, including the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula.

“I suspected that many regions with high diversity would be well-studied and protected,” Espíndola says in the statement, “but we found the opposite to be true. Many of the high-diversity areas corresponded to regions with the highest probability of risk.”

Wired’s Barber offers a partial explanation for this trend, noting that plant conservation efforts tend to center on Europe, which hosts many of the world’s top research institutions, or “ecological marvels” like Madagascar. This limited geographic scope acts as a detriment to the study and assessment of more obscure plants.

Overlooking at-risk plants in general poses significant risks, according to the study: Not only do plants contribute to the diversification of Earth’s organisms, but they can also prevent natural disasters such as flooding and foster overall ecosystem productivity. When plants become extinct, Barber writes, their disappearance can have a cascading effect on broader ecological networks.

As study co-author Bryan Carstens of Ohio State explains, plants should be considered a top conservation priority because they form the basic habitat upon which all other species rely.

“People focus on big, charismatic animals, but it’s actually habitat that matters,” he says in a statement. “We can protect all the lions, tigers and elephants we want, but they have to have a place to live in.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)