Dictators have long relied on propaganda to fuel their regime’s ideology and centralize power. Adolf Hitler, for instance, employed a personal photographer who captured more than 2 million snapshots of the Nazi leader, while Josef Stalin used doctored images to erase all evidence of “purged” political enemies.

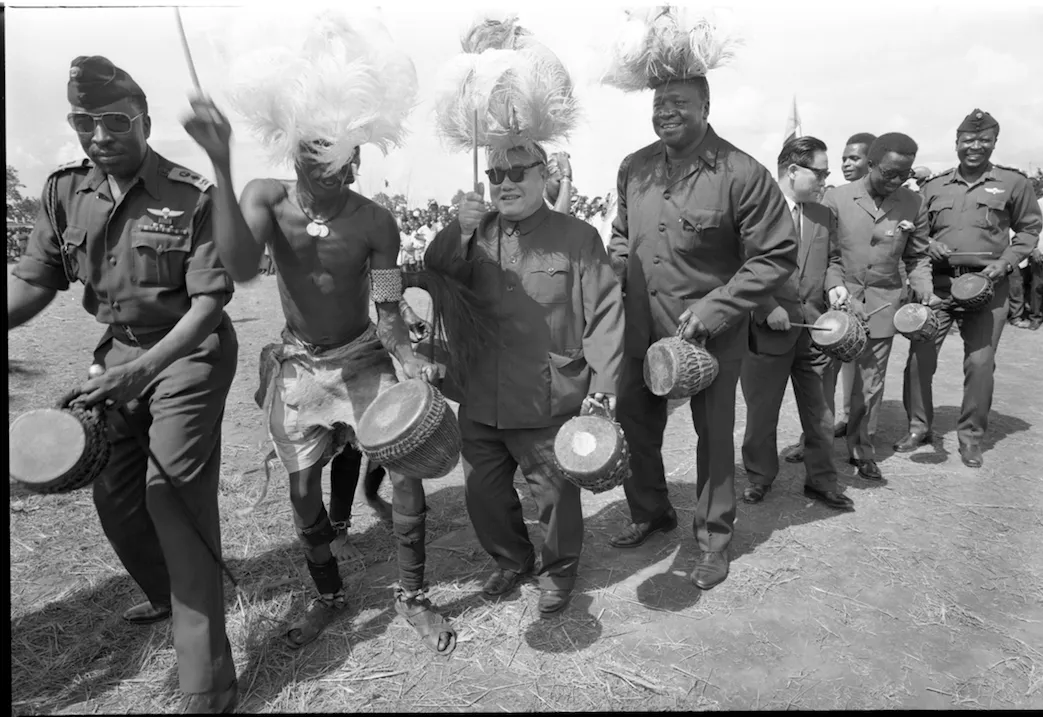

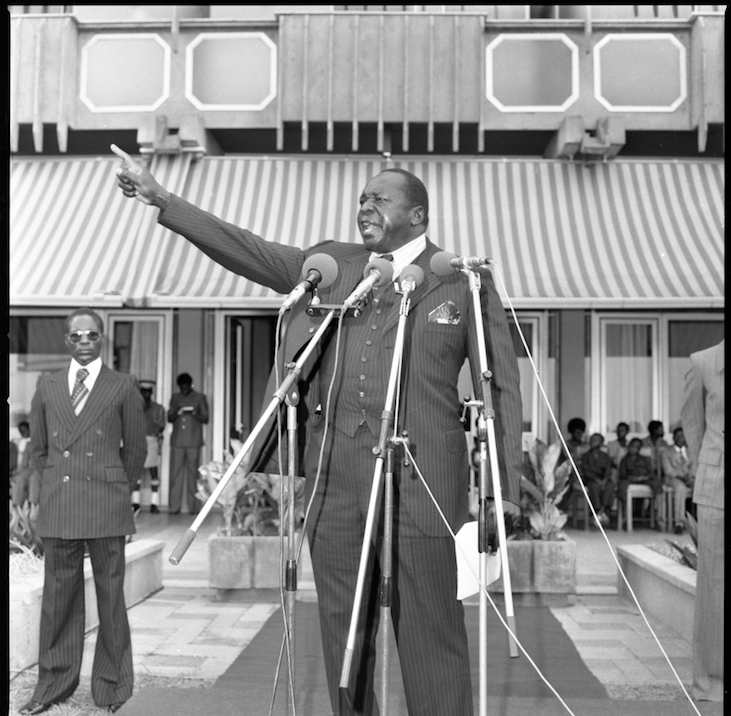

Idi Amin, a Ugandan general who seized power in a 1971 coup and launched an eight-year reign of terror that left as many as 300,000 civilians dead, was no different: As historian Derek R. Peterson and anthropologist Richard Vokes write for the Conversation, government photographers were a “constant presence” in Amin’s Uganda, documenting the dictator’s public appearances and providing evidence of social issues—including smuggling and South Asians’ economic dominance—purportedly plaguing the country at the time. What the cameras largely left out, however, was the regime’s brutal treatment of those who opposed or were affected by Amin’s authoritarian policies.

Upon Amin’s fall from power, the hundreds of thousands of images taken by his official photographers disappeared from the historical record, presumed lost or destroyed during the tumultuous years that followed. But in 2015, a chance discovery at the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) offices led researchers to a trove of some 70,000 negatives dating to the dictator’s reign. Thanks to a collaboration between the University of Michigan, the University of Western Australia, Makerere University and the UBC, the public can now see a selection of these never-before-seen photographs for the very first time.

The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin: Photographs From the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation opened at the Uganda Museum in Kampala this May. On view through November 30, the exhibition—curated by the museum’s Nelson Abiti, the University of Michigan’s Peterson, the Centre for Indian Studies in Africa’s Edgar C. Taylor and the University of Western Australia’s Vokes—features around 150 newly digitized images that show what life was like under the dictator’s rule. (To date, researchers have digitized 25,000 of the 70,000 total negatives.)

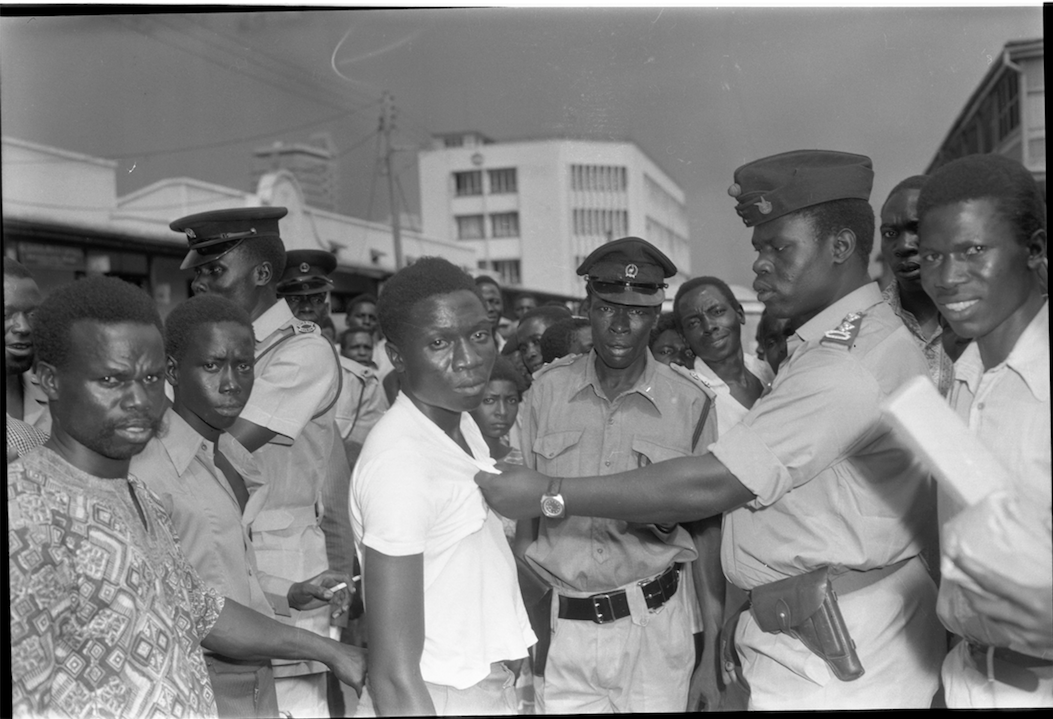

In one section of the exhibition, portraits of those killed by Amin’s henchmen are presented alongside snapshots of cultural and political events; in another, pictures of defining episodes such as the expulsion of Uganda’s Asian community and the Economic Crimes Tribunal are the focus. Images of the Amin government’s torture chambers, as photographed by members of the dissident Uganda National Liberation Front, punctuate the end of the series.

“Our exhibition works by placing the grand images of public life—most of which are focused on Amin himself—with images of those who suffered or were killed during the 1970s,” Peterson states in a University of Michigan press release. “The idea is to juxtapose different kinds of historical experiences, different ways of seeing the time, so as to enable a pluralistic understanding of the past.”

Speaking with Ugandan daily New Vision, Peterson points out that the curators were especially “mindful that these photographs were produced by official photographers who had an interest in portraying the Amin government in a positive light.”

He adds, “We have presented these photos in a way that does not reinforce the regime’s propaganda.”

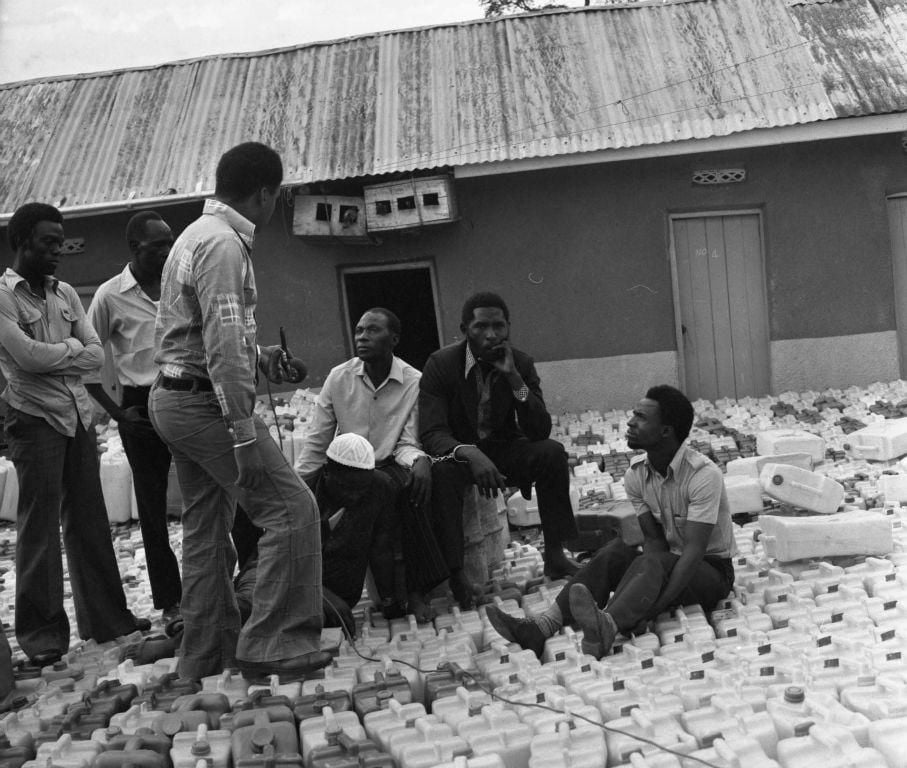

Perhaps the most obvious examples of the images’ underlying political bent are those depicting criminal activities. As Peterson and Vokes note for the Conversation, the archive includes photographs of smugglers’ paraffin stashes, piles of hoarded cash and traders under arrest for selling overpriced goods. Amin stoked public outrage over “otherwise obscure social issues” by strategically disseminating these visuals and used them to gain support for acts like his expulsion of tens of thousands of South Asians in 1972.

EastAfrican newspaper’s Bamuturaki Musinguzi reports The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin juxtaposes horrific moments—including public executions and floggings—with photographs depicting “joy and merrymaking, love and celebration, the performing arts and sports.” Although many of the images are reflective of the propaganda lens through which they were filmed, the experiences and emotions on display are largely genuine, testifying to “the passions and enthusiasms” Amin’s regime was able to stoke.

“The positive and uplifting photos in this collection mask the harsh realities of public life at this time: unaccountable violence, a collapsing infrastructure, and shortages of the most basic commodities," an exhibition flyer states.

The exhibition is not a comprehensive exploration of all aspects of Amin’s regime. Rather it aims to act as a space for reflection and discussion. To support this goal, the museum has hosted a series of panels featuring individuals who lived through the dictator’s rule: politicians who served in his cabinet, journalists who wrote about his government, and some of the many who lost loved ones at the hands of Amin.

“There’s never been a public exhibition in Uganda about Idi Amin; neither is there a museum, or a monument, or a memorial to the time,” Peterson states in a press release. “There is no narrative around which to hang this story.”

The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin: Photographs From the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation is on view at the Uganda Museum in Kampala through November 30, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/59/9659e5d3-b421-4149-8f2f-230ce66d1ee0/3131-4-011_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)