Thousands of Rare Artifacts Discovered Beneath Tudor Manor’s Attic Floorboards

Among the finds are manuscripts possibly used to perform illegal Catholic masses, silk fragments and handwritten music

:focal(2523x1261:2524x1262)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/94/9194c6ff-c736-4d09-9ce1-033ca4cfaa35/oxburgh_hall_16_scaffolding_goes_up_national_trust_images_ian_ward.jpg)

While most of England was on lockdown amid the COVID-19 pandemic, archaeologist Matt Champion was working solo at Oxburgh Hall, a moated Tudor mansion in Norfolk.

As part of the site’s £6 million (roughly $7.8 million) roof restoration project, workers had lifted the floorboards in the estate’s attic for the first time in centuries. Probing the recesses beneath the boards with gloved fingertips, Champion expected to find dirt, coins, bits of newspapers and detritus that had fallen through the cracks. Instead, he discovered a veritable treasure trove of more than 2,000 items dating as far back as the 15th century.

The cache is one of the most remarkable “underfloor” archaeological finds ever made at a National Trust property, the British heritage organization says in a statement. Together, the objects offer a rich social history of the manor’s former residents.

Among the discoveries are the nests of two long-gone rats that built their homes out of scraps of Tudor and Georgian silks, wools, leather, velvet, satin and embroidered fabrics, reports Mark Bridge for the London Times.

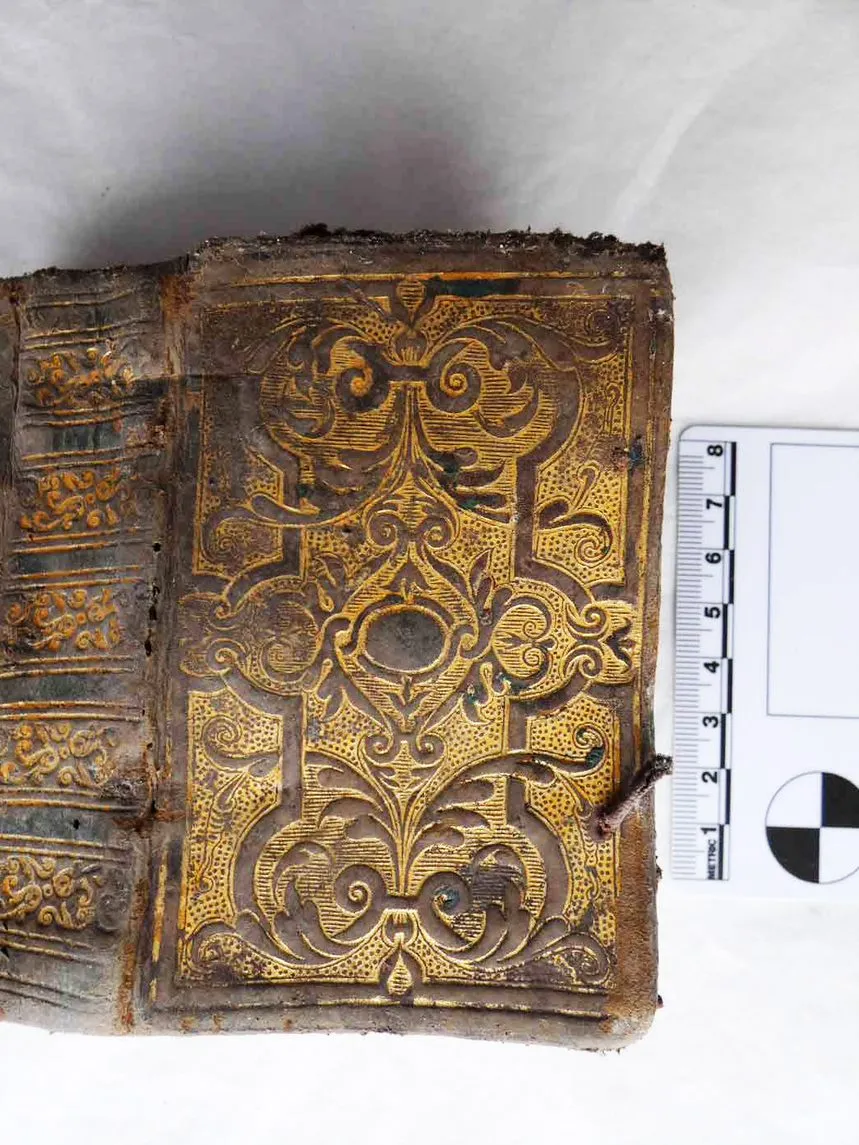

The critters also repurposed roughly 450-year-old fragments of handwritten music and parts of a book. A builder recently found the rest of the volume—a relatively intact 1568 copy of Catholic martyr John Fisher’s The Kynge’s Psalmes—in a hole in the attic.

Another worker discovered a rare item in the rubble underneath one of the attic’s eaves. Per the statement, the team collaborated with James Freeman, a medieval manuscripts specialist at Cambridge University Library, to identify the 600-year-old parchment fragment, still glimmering with gold leaf and bright blue ink, as part of the Latin Vulgate’s Psalm 39.

“The use of blue and gold for the minor initials, rather than the more standard blue and red, shows this would have been quite an expensive book to produce,” National Trust curator Anna Forrest notes in the statement.

She adds that the page’s small size indicates it was probably part of a Book of Hours, or portable prayer book meant for personal use.

“It is just the most exquisite thing, and to have found it literally in a pile of rubble is probably … well, it’s unheard of for the National Trust, that’s for sure,” Forrest tells the Guardian’s Mark Brown.

British nobleman Sir Edmund Bedingfeld built the manor house in 1482, reports BBC News. His descendants live in the home to this day.

As devout Catholics, the Bedingfelds were ostracized for their faith, particularly after Elizabeth I succeeded to the throne in 1558. The year after the Protestant queen’s ascension, Sir Henry Bedingfeld refused to sign the Act of Uniformity, which outlawed Catholic mass, according to the statement.

During the Elizabethan period, many Catholic clergy were imprisoned, tortured and killed. The Bedingfelds hid men of the cloth in a secret “priest hole” at their home and participated in secret masses, per the Times. The religious artifacts discovered in the attic may have been used in these illegal services.

Researchers also uncovered tiny fragments thought to come from a 1590 edition of a Spanish chivalric romance book, The ancient, famous and honorable history of Amadis de Gaule. In the statement, the trust notes that Catholics often read Spanish romances, which included references to mass and other Catholic themes, during this time of persecution.

Other attic finds—most prominently, a box of chocolates—date to World War II. Given the fact that the box contains all of its wrappings but no candy, the team suggests that someone may have squirreled the box away after eating a hidden treat. The archaeologists also discovered wartime Woodbine cigarette packets and scraps of newspapers.

“[I]t really feels like [these artifacts] are shining a window on the world of the Bedingfelds from centuries ago,” Forrest tells the Times. “It’s telling us what they wore, what they did in their spare time, what they were reading, possibly even what music they were playing. It’s incredible.”

Speaking with BBC News, the curator notes that the artifacts spent decades resting beneath thick dust and a layer of lime plaster, which drew moisture out of the air and helped “perfectly” preserve the fragile paper fragments.

As Russell Clement, general manager at Oxburgh Hall, says in the statement, “[T]hese finds are far beyond anything we expected to see.”

He adds, “These objects contain so many clues which confirm the history of the house as the retreat of a devout Catholic family, who retained their faith across the centuries. … This is a building which is giving up its secrets slowly. We don’t know what else we might come across—or what might remain hidden for future generations to reveal.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/e1/3ce1d0ea-b94d-4508-bc24-b1bf71b8dc89/oxburgh_archaeology_2_-_a_15th_century_illuminated_manuscript_cnational_trust_mike_hodgson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/a8/b0a87c7a-bd08-461a-9ad1-5d2c627ae016/oxburgh_archaeology_4_-_curator_anna_forest_examines_fragment_of_18th_century_document_cnational_trust_mike_hodgson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/d4/87d4bc0b-5143-4d07-87d6-9f1af9a7069a/oxburgh_archaeology_7_-_archaeologist_matt_champion_looks_under_the_floorboards_cnational_trust_-_mike_hodgson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/a8/f3a83fd8-dde0-4a82-93d3-1b8f7b21c438/oxburgh_archaeology_9_curator_anna_forest_examines_a_15th_century_illuminated_manuscript_cnational_trust_mike_hodgson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/03/a2036d83-310c-434a-8333-3e19e5a64272/oxburgh_archaeology_5_-_curator_anna_forest_examines_large_piece_of_slashed_brown_silk_shot_through_with_goldcnational_trust_mike_hodgson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/a3/27a3281b-e28c-48e9-bd04-b27365b59529/oxburgh_hall_13_sir_henry_bedingfeld_princess_elizabeths_jailor_cnational_trust_images_-_jim_woolf.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/73/d073013f-bfc4-4d05-ad16-70252f939ba0/oxburgh_archaeology_14_-_a_war_time_chocolate_box_national_trust_images_matt_champion.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)