On the day of Queen Victoria’s engagement to Prince Albert, the future prince consort wrote, “How is it that I have deserved so much love, so much affection?” Addressing his bride-to-be in the October 15, 1839, missive, he further confessed, “I cannot get used to the reality of all that I see and hear, and have to believe that Heaven has sent me an angel whose brightness shall illumine my life.”

The intimate note is among the more than 17,500 photographs, prints and papers digitized by the United Kingdom’s Royal Collection in honor of Albert’s 200th birthday. Encompassing artistic gifts exchanged by the royal couple, government paperwork written in his capacity as the queen’s unofficial private secretary, family photographs and a myriad of documents related to miscellaneous topics, the Prince Albert Digitisation Project is set to make the historic collection readily available to the public for the first time.

Per the Associated Press’ Mike Corder, the portal offers new insights on the life of an individual most often remembered for his untimely death at age 42. By drawing attention to a wide range of little-known sources, “Prince Albert: His Life and Legacy” emphasizes Albert’s role in shaping Victorian society, particularly in terms of the arts and sciences, as well as his outspoken passion for social reform. (Helen Trompeteler, project manager and senior curator of photographs at the Royal Collection, tells Corder the prince was “certainly the most prominent member of the royal family to speak on the issue of the abolition of slavery.”)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/6a/436a5e46-b271-4b8f-8515-35339c58020b/2940.jpg)

According to a press release, curators plan to digitize a total of 23,500 items from the Royal Archives, the Royal Collection and the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851—spearheaded by Albert and arts patron Henry Cole, the unparalleled display of wonders from around the world attracted 6 million visitors over just five months—by the end of 2020. Ultimately, the “Prince Albert: His Life and Legacy” project will include some 10,000 photographs collected and commissioned by the royal consort, 30 volumes of correspondence regarding the Great Exhibition of 1851, and more than 5,000 prints and photographs documenting almost the entirety of Raphael’s oeuvre.

As the Royal Collection Trust notes, Albert embarked on the latter undertaking in 1853, tracking down prints and paintings from both the British monarchy’s holdings and other major collections to create a comprehensive photographic catalogue of the Renaissance Old Master’s body of work. By 1876, Albert and his staff had enough material to constitute 25 different categories, from portraits to Old Testament subjects, saints, mythology and Vatican frescoes. Today, large-scale versions of these images are stored in 49 portfolios in a custom-made cabinet at Windsor Castle.

The broader set of digitized photographs reflects the prince’s unexpected views on the medium: Whereas the majority of Victorians only recognized the camera’s scientific value, Albert advocated for its use as an artistic avenue, documentary device and means of sharing knowledge.

“He sincerely believed in photography as an art form at a time when its role in society was being debated,” Trompeteler of the Royal Collection tells the Guardian’s Mark Brown. “He really saw photography’s potential across every aspect of society, from art to historical record to being a tool for arts scholarship.”

The photography section of the new portal features portraits, landscape scenes, images of political and military events, glass plate negatives revealing photographers’ working methods, snapshots taken by the royal couple’s nine children, and memorial works commissioned by Victoria following her husband’s death from typhoid in 1861.

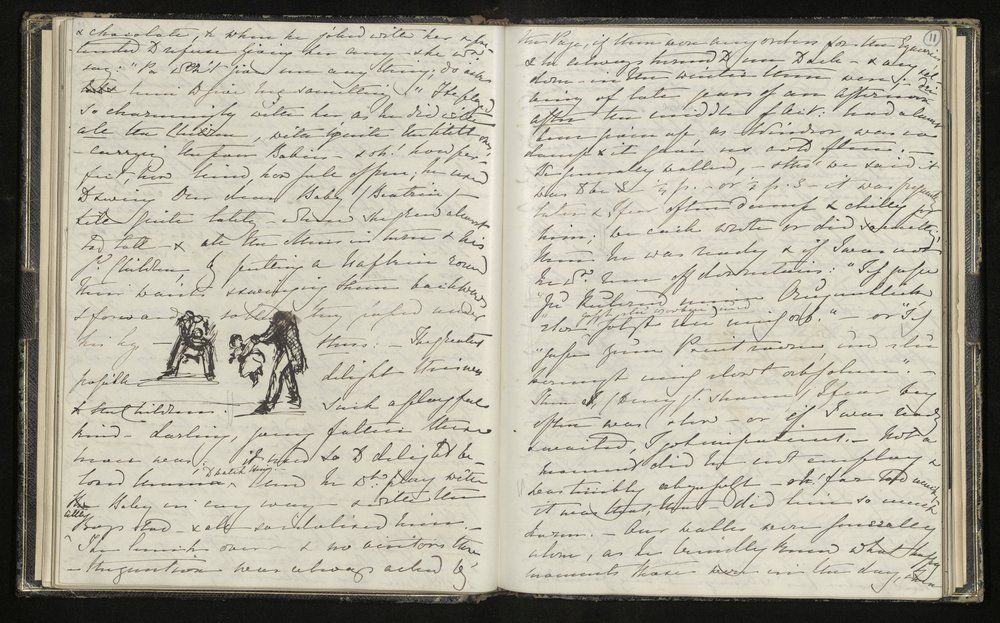

Albert’s passing devastated the queen, who famously donned mourning clothes for the remainder of her reign. (She died in 1901, a full 40 years after her beloved consort.) As the AP’s Corder reports, Victoria’s handwritten account of Albert’s death is among the documents now available online; written 10 years after the fact, the moving remembrance finds the queen admitting, “I have never had the courage to attempt to describe this dreadful day.”

As Albert died, Victoria “kissed his dear heavenly forehead and called out in a bitter and agonizing cry: ‘Oh! My dear Darling!’ then dropped on my knees in mute, distracted despair, unable to utter a word or shed a tear!”

Speaking with Corder, Trompeteler says the account “reflects upon obviously the impact that Albert continues to have on her throughout her many extended years of mourning.“

“It’s a testament," she continues, "to the remarkable partnership that they had.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/90/f3907dcc-dcce-4d91-bae6-7ac0c6b81fef/2468.jpg)

:focal(395x362:396x363)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/61/e8617cf0-3d40-41bd-8163-2798f0d14860/1000.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)