Three Things to Know About Benjamin Banneker’s Pioneering Career

Banneker was a successful almanac-maker and self-taught student of mathematics and astronomy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/46/fc4613f8-8c91-4223-8eb4-da7fa174bfbe/banneker-stamp.jpg)

Today is the 286th birthday of one of early America’s most fascinating figures.

Benjamin Banneker, born on this day in 1731, is remembered for producing one of America’s earliest almanacs and what may have been the country’s first natively produced clock. Banneker, who was black, had “significant accomplishments and correspondence with prominent political figures [which] profoundly influenced how African Americans were viewed during the Federal period,” writes the Library of Congress.

Because of his accomplishments and the unique place he occupied in early American society, Banneker is well-remembered–perhaps too well, given the number of myths surrounding his life. While it’s (probably) not true that he saved the plan of Washington, D.C., Banneker did make some important contributions to early America. Here are three you may not have heard about.

He built America’s first home-grown clock–out of wood

Banneker was 22 in 1753, writes PBS, and he’d “seen only two timepieces in his lifetime–a sundial and a pocket watch.” At the time, clocks weren’t common in the United States. Still, based on these two devices, PBS writes, “Banneker constructed a striking clock almost entirely out of wood, based on his own drawings and calculations. The clock continued to run until it was destroyed in a fire forty years later.”

This creation, which is believed to be the first clock built in America, made him famous, according to the Benjamin Banneker Memorial’s website. People traveled to see the clock, which was made entirely out of hand-carved wooden parts.

He produced one of the United States’ first almanacs

Banneker, whose schooling and scientific training was minimal, had a clear talent for mathematics and machines, writes the Library of Congress. He was also a talented astronomer–a skill that proved useful in producing the Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanac and Ephemeris, which he published from 1791 to 1802.

“Banneker spent most of his life on his family’s 100-acre farm outside Baltimore,” writes the Library of Congress. “There, he taught himself astronomy by watching the stars and learned advanced mathematics from borrowed textbooks.”

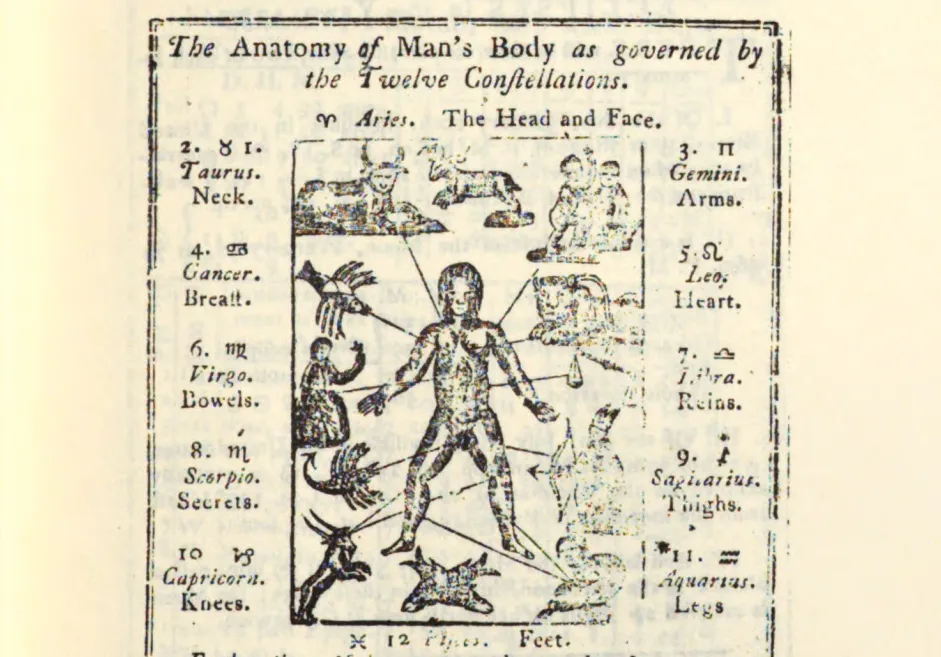

As a gentleman farmer, Banneker had many opportunities to examine the natural world around him. Many of those insights were captured in the Almanac or his other writings. His almanac predicted eclipses and other astronomical events, offered medical information and listed the tides, the Library writes. It “also included commentaries, literature, and fillers that had a political and humanitarian purpose,” writes PBS, such as an excerpt from an anti-slavery poem in the 1793 edition.

He wrote to Thomas Jefferson–and Jefferson wrote back

In 1791, when Banneker was fifty-nine, he sent a copy of the almanac for 1792 to Thomas Jefferson, who was then the U.S. secretary of state (and, as history records, a slaveholder). Included with that almanac was a now-famous letter to Jefferson. Scholar Angela G. Ray writes:

Claiming that he simply intended to direct to Jefferson “as a present, a copy of an Almanack which I have calculated for the Succeeding year,” Banneker wrote that his “Sympathy and affection for [his] brethren” led him “unexpectedly and unavoidable” to take the opportunity to condemn endemic prejudice and the “groaning captivity and cruel oppression” of slavery. Justifying his right to speak to the secretary of state on such a topic, Banneker argued from moral compulsion based on recognition of deep injustice. He spoke not as a representative slave but as a more fortunate “brother” of slaves, obliged to use his abilities to advance the cause of others of his race. Emphasizing the discrepancy between the rhetoric of equality found in the Declaration of Independence and the physical fact of slavery, Banneker denounced the institution that he called “that State of tyrannical thraldom, and inhuman captivity.”

The letter reached Jefferson, who responded “by expressing his ambivalence about slavery and endorsing Banneker’s accomplishments,” the Library of Congress writes. Banneker’s feelings on this lukewarm response are not documented.