Venetian Glass Beads May Be Oldest European Artifacts Found in North America

Traders likely transported the small spheres from Italy to northern Alaska in the mid-15th century

:focal(388x289:389x290)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/8b/798b0a66-3e73-46e3-84f7-d8ddfd78e13a/beads2.jpg)

More than five centuries ago, a handful of blueberry-sized blue beads made an astonishing journey.

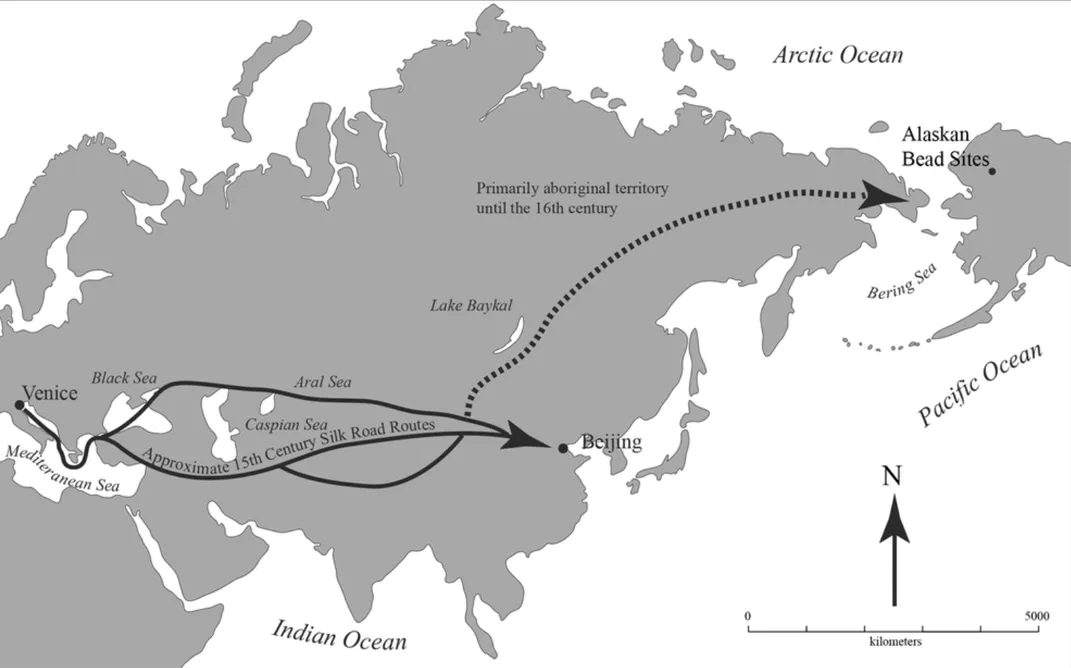

Crafted by glassmakers in Venice, the small spheres were carried east along Silk Road trade networks before being ferried north, into the hinterlands of Eurasia and across the Bering Strait, where they were deposited in the icy ground of northern Alaska.

Archaeologists dug the beads up in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Now, a new study published in the journal American Antiquity asserts that the glass objects are among the oldest European-made items ever discovered in North America.

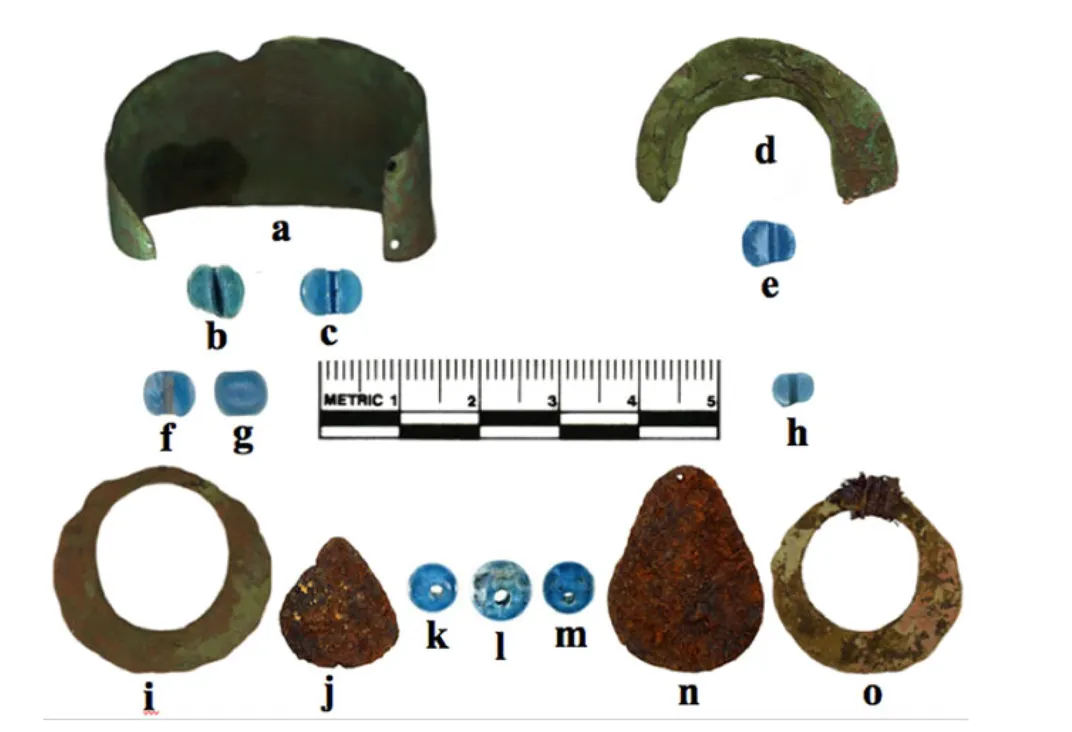

Per the paper, Michael Kunz of the University of Alaska Museum of the North and Robin Mills of the Bureau of Land Management studied ten glass beads found at three sites along Alaska’s Brooks Range. The researchers used mass spectrometry carbon-dating to analyze trace amounts of twine discovered alongside three of the beads and date the artifacts’ creation to between roughly 1397 and 1488.

Unlike glass, twine is made from organic material—in this case, plant fibers—and can therefore be carbon dated, notes Jack Guy for CNN. The twine used to date the beads was found on copper bangles buried nearby, leading the researchers to posit that the beads and copper jewelry were once used as earrings or bracelets.

When the archaeologists realized how old the beads were, “[w]e almost fell over backwards,” says Kunz in statement. “It came back saying [the plant was alive at] some time during the 1400s. It was like, Wow!”

As the authors note in the paper, “trade beads” such as these have been found in North America before, including in the eastern Great Lakes region and the Caribbean. But those beads dated to between 1550 and 1750, according to Gizmodo’s George Dvorsky.

“This is the first documented instance of the presence of indubitable European materials in prehistoric sites in the Western Hemisphere as the result of overland transport across the Eurasian continent,” add the authors.

The discovery indicates the wide reach of 15th-century trade networks. Per CNN, Kunz and Mills theorize that the beads were carried along East Asian trade routes to the trading post of Shashalik and then on to Punyik Point, an ancient Alaskan settlement en route from the Arctic Ocean to the Bering Sea. Someone would have had to carry the beads across the Bering Strait—a journey of about 52 miles of open ocean, likely traversed in a kayak.

Punyik Point was a site well-suited to caribou hunting, says Kunz in the statement.

“And, if for some reason the caribou didn’t migrate through where you were, Punyik Point had excellent lake trout and large shrub-willow patches,” he adds.

The beads discovered at Punyik Point were likely strung into a necklace and later dropped near the entrance to an underground house.

If confirmed, the scientists’ discovery would indicate that Indigenous North Americans trading in northern Alaska wore European jewelry decades before Christopher Columbus’ 1492 landing in the Bahamas. In the centuries after Columbus’ arrival, European colonizers waged war on Indigenous people for their land and resources, introduced deadly diseases, and initiated the mass enslavement of Indigenous Americans.

Ben Potter, an archaeologist at the Arctic Studies Center at Liaocheng University in China who was not involved in the study, tells Gizmodo that the findings are “very cool.”

“The data and arguments are persuasive, and I believe their interpretation of movement of the beads through trade from East Asia to the Bering Strait makes sense,” Potter says. “There are other examples of bronze making its way into Alaska early as well, so I think the idea of long-distance movement of items, particularly prestige [small, portable, and valuable items] moving long distances is understandable.”

In another example of the surprising interconnectedness of the medieval world, a metal detectorist recently found a Northern Song Dynasty coin in a field in Hampshire, England. Dated to between 1008 and 1016, the copper-alloy token was the second medieval Chinese coin discovered in England since 2018, per the Independent’s Jon Sharman.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)