Study Rewrites History of Ancient Land Bridge Between Britain and Europe

New research suggests that climate change, not a tsunami, doomed the now-submerged territory of Doggerland

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/72/87721437-be66-4d19-bae0-90bc9e7cfd6e/doggerland2sml-1-700x715.jpg)

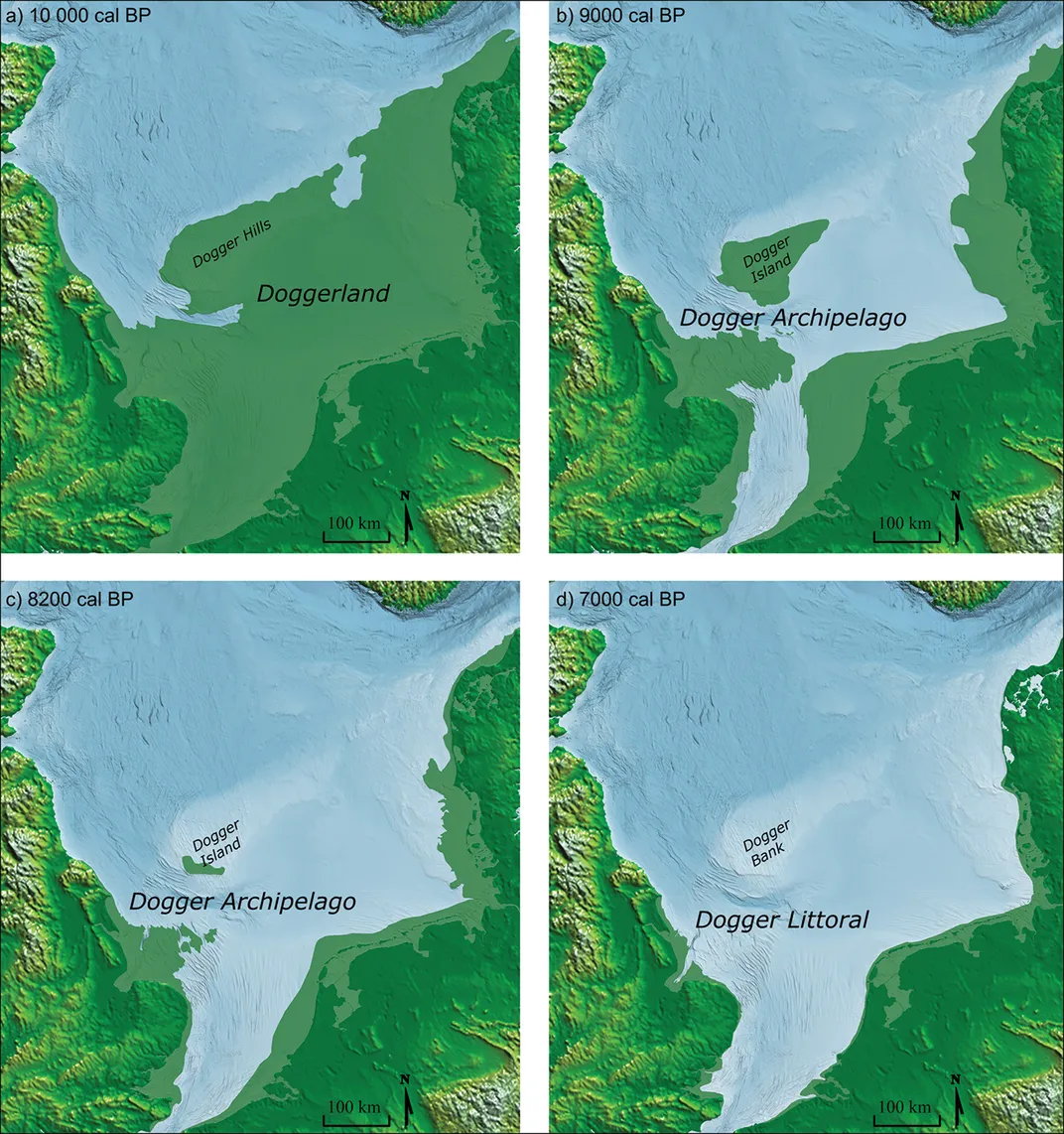

As recently as 20,000 years ago—not long in geological terms—Britain was not, in fact, an island. Instead, the terrain that became the British Isles was linked to mainland Europe by Doggerland, a tract of now-submerged territory where early Mesolithic hunter-gatherers lived, settled and traveled.

Doggerland gradually shrank as rising sea levels flooded the area. Then, around 6150 B.C., disaster struck: The Storegga Slide, a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway, triggered a tsunami in the North Sea, flooding the British coastline and likely killing thousands of humans based in coastal settlements, reports Esther Addley for the Guardian.

Historians have long assumed that this tsunami was the deciding factor that finally separated Britain from mainland Europe. But new archaeological research published in the December issue of Antiquity argues that Doggerland may have actually survived as an archipelago of islands for several more centuries.

Co-author Vincent Gaffney, an archaeologist at the University of Bradford, has spent the past 15 years surveying Doggerland’s underwater remains as part of the Europe’s Lost Frontiers project. Using seismic mapping, computer simulations and other techniques, Gaffney and his colleagues have successfully mapped the territory’s marshes, rivers and other geographical features.

For this recent study, the team of British and Estonian archaeologists drew on topography surveys and data obtained by sampling cores of underwater rocks. One sample gathered off of the northern coast of Norfolk contained sedimentary evidence of the long-ago Storegga flood, per the Guardian. Sampling the underwater sediment cores was in and of itself a “major undertaking,” Karen Wicks, an archaeologist at the University of Reading who wasn’t involved in the research, tells Michael Marshall of New Scientist.

According to their revised history, the study’s authors estimate that by about 9,000 years ago, rising sea levels linked to climate change had already reduced Doggerland to a collection of islands. Though the later tsunami wreaked havoc on the existing hunter-gatherer and fishing societies that lived along the British coast, pieces of the landmass—including “Dogger Island” and “Dogger Archipelago,” a tract roughly the size of Wales—likely survived the cataclysmic event, reports Ruth Schuster for Haaretz.

Still, notes New Scientist, while some parts of the land were protected from the brunt of the waves, others were buffeted by waves strong enough to rip trees from their sides.

“If you were standing on the shoreline on that day, 8,200 years ago, there is no doubt it would have been a bad day for you,” Gaffney tells the Guardian. “It was a catastrophe. Many people, possibly thousands of people, must have died.”

The scientists note that this revised history of Doggerland could shift scholars’ understanding of how humans arrived in Britain. As Brooklyn Neustaeter reports for CTV News, the Dogger archipelagos could have served as a staging ground for the first Neolithic farmers, who moved into Britain and began to build permanent settlements on the island. This transition to farming took place some 6,000 years ago, per London’s Natural History Museum.

By about 7,000 years ago, the study suggests, Doggerland would have been long gone, completely submerged by rising sea levels.

“Ultimately, it was climate change that killed Doggerland,” Gaffney tells Haaretz.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)