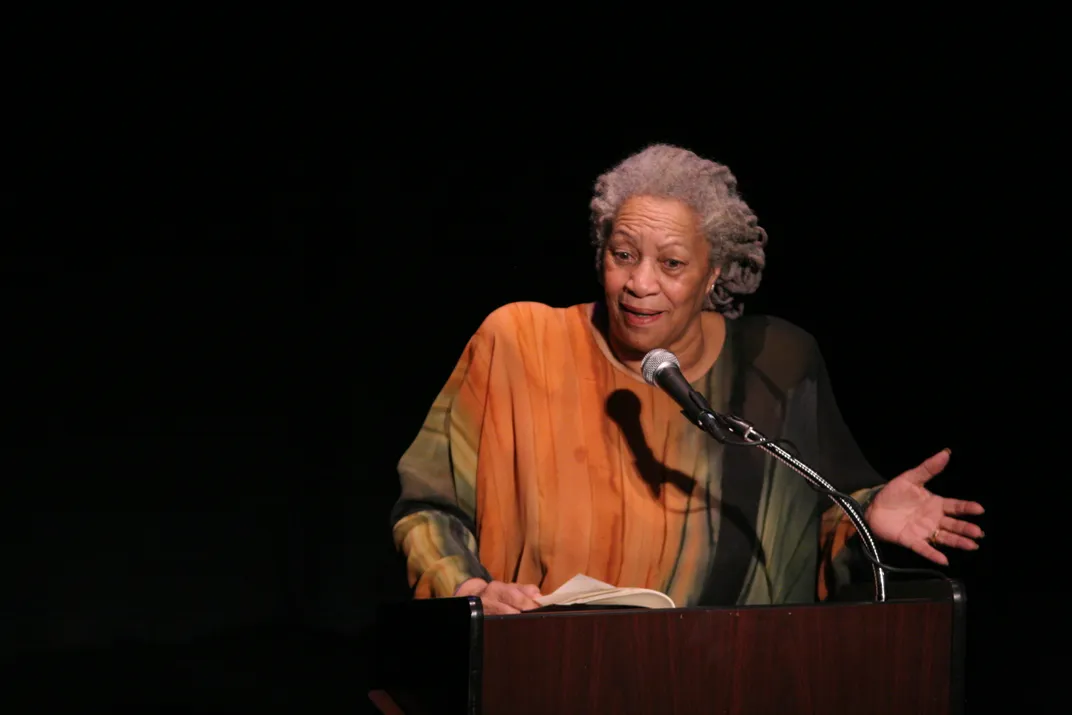

Toni Morrison, ‘Beloved’ Author Who Cataloged the African-American Experience, Dies at 88

‘She changed the whole cartography of black writing,’ says Kinshasha Holman Conwill of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

:focal(999x1046:1000x1047)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/80/1f80011d-68e3-4e87-8792-85e7cee61445/l_npg_2_2006_morrison_r.jpg)

When Toni Morrison accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993, she had this to say: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

Leave it to Morrison to always find the right words, even from beyond the grave. Morrison—award-winning author of novels including Beloved, Sula and Song of Solomon, as well as children’s books and essay collections—died at a New York hospital on August 5 following a short illness. The 88-year-old literary giant’s passing was announced by her publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, this morning. A spokesperson identified the cause of death as complications stemming from pneumonia.

“Her legacy is made,” Spencer Crew, interim director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, tells Smithsonian. “It doesn’t have to be bolstered or created or made stronger.”

Lauded for her lyrical writing style and unflinching depictions of the African-American experience, the Nobel Laureate, Pulitzer Prize winner and Medal of Freedom recipient created such memorable characters as Pecola Breedlove, a self-loathing 11-year-old who believes the only cure to her “ugliness” is blue eyes; Sethe, a woman who escaped slavery but is haunted by the specter of her young daughter, whom she killed because she decided death was a better fate than life in bondage; and Macon “Milkman” Dead III, a privileged, alienated young man who embarks on a journey of self-discovery in rural Pennsylvania.

Morrison’s work brought African-Americans, especially African-American women, to the literary forefront. As Emily Langer writes for the Washington Post, the author translated “the nature of black life in America, from slavery to the inequality that went on more than a century after it ended.” Whereas the mid-20th century was flush with books that constructed worlds populated by white characters, Morrison described environments punctuated by their absence; at the same time, Margalit Fox notes for the New York Times, she avoided writing about stereotypically “black settings,” declaring in a 1994 interview that her subjects lived in “neither plantation nor ghetto.”

Kinshasha Holman Conwill, deputy director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, emphasizes Morrison’s ability to generate empathy for her flawed, tortured, “fully realized” characters.

“You could not tell stories that were so very painful, and actually horrific in many cases, if you did not have what Ms. Morrison had, which was just a brilliant imagination and the ability to translate that imagination into words,” Conwill tells Smithsonian.

Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford in the working-class community of Lorain, Ohio, on February 18, 1931. The daughter of a shipyard welder and granddaughter of a slave, she changed her name to Toni—short for Anthony, her Roman Catholic baptismal name—as an undergraduate at Howard University. After graduating in 1953, Morrison went on to earn a master’s in English from Cornell University and began a career in academia. She married architect Harold Morrison in 1958 but got divorced in 1964, moving to Syracuse, New York, with her two young sons to begin working as an editor at Random House shortly thereafter.

Morrison’s first book, The Bluest Eye, was published in 1970. Written in between work and motherhood, the novel grew out of the author’s desire to see young black girls depicted truthfully in literature. “No one had ever written about them except as props,” she said in a 2014 interview.

At first, her debut novel received little attention. Still, Conwill says, The Bluest Eye, a heart-wrenching exploration of Pecola’s struggle for love and validation in the face of ingrained racist values, did introduce her to editors who boosted her career, which was further advanced by 1973’s Sula and 1977’s Song of Solomon.

Beloved, Morrison’s best-known novel, followed in 1987. Loosely based on the story of Margaret Garner, a woman born into slavery who slit her two-year-old daughter’s throat after a failed escape attempt, the seminal text won the author a Pulitzer Prize for fiction and was later adapted into a film starring Oprah Winfrey.

Beloved is part ghost story, part historical fiction. As Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, senior historian at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, explains, it demonstrates “the ways that the scars of American slavery … are borne not just on their immediate descendants and survivors but into the present day.”

This same undercurrent is apparent across Morrison’s genre-bending oeuvre, as well as in her efforts to elevate other black voices. By placing black authors within the wider nexus of American literature and showing that their “contributions would stand alongside all of their peers throughout history,” Conwill says, “[Morrison] changed the whole cartography of black writing.”

“Other writers looked to her as a touchstone,” she adds.

Since the news of Morrison’s death broke, there has been an outpouring of tributes. Former President Barack Obama, who presented the author with the Medal of Freedom in 2012, described her as a “national treasure, as good a storyteller, as captivating, in person as she was on the page.” Filmmaker Ava DuVernary, meanwhile, wrote, “Your life was our gift.”

In a statement released by Princeton University, where Morrison was a longtime lecturer, family members said, “Our adored mother and grandmother, Toni Morrison, passed away peacefully last night surrounded by family and friends. She was an extremely devoted mother, grandmother, and aunt who reveled in being with her family and friends. The consummate writer who treasured the written word, whether her own, her students or others, she read voraciously and was most at home when writing. Although her passing represents a tremendous loss, we are grateful she had a long, well lived life.”

A portrait of Morrison by artist Robert McCurdy is currently on view in the National Portrait Gallery’s 20th Century Americans exhibition. The painting depicts the author without background or setting, offering no indication of any historical moment or location. Much like her literary legacy, the work appears to transcend time and space. “She seems to have always been there and will always be,” Shaw says. “As opposed to looking back into a specific moment, she's right here in the present.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)