The Tragic Life of Hansken, ‘Rembrandt’s Elephant’

A new show at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam explores the story of an animal who fascinated the Dutch artist

:focal(446x217:447x218)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/75/db7566f5-668d-4e14-a08c-02819a3b2693/hanskenrembrandt.jpg)

In the mid-17th century, residents of Amsterdam flocked to see a strange and incredible sight: an Asian elephant, imported from Sri Lanka, who could perform a repertoire of tricks. Among those dazzled by this exotic creature, known by the name Hansken, was the preeminent Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn. Now, reports Nina Siegal for the New York Times, an exhibition at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam explores the artist’s fascination with Hansken—and highlights her tragic life as a spectacle in a foreign land.

Rembrandt drew detailed sketches of Hansken, in addition to including her in his 1638 etching Adam and Eve in Paradise, where she represents chastity and grace.

“[These] drawings of Hansken really show him observing closely and with great interest,” says curator Leonore van Sloten in a statement. “[H]e drew her ‘after life,’ with attention to every detail including her short hairs, skin folds and the movement of her feet and trunk.”

The exhibition, titled “Hansken, Rembrandt’s Elephant,” features works by other artists who were similarly enthralled by the animal, along with historical documents and a digital map tracing her performances across Europe.

Hansken was born in Sri Lanka, known at the time as Ceylon, in 1630. After parts of the island came under the control of the Dutch East India Company in the early 17th century, officials there received a request from Prince Frederick Henry, sovereign representative of the Dutch Republic, to supply him with a young elephant. In 1633, when she was 3 years old, Hansken was taken by boat to the Netherlands, where she was housed in the royal’s stables.

According to Jan Pieter Ekker of Amsterdam-based newspaper Het Parool, Hansken changed hands multiple times before being purchased by one Cornelis van Groenevelt for 20,000 guilders—around $500,000 today. Van Groenevelt spent the next two decades transporting Hansken from place to place as a touring attraction; Rembrandt probably first saw her in 1637, during one of her visits to Amsterdam. Hansken would have been a stunning sight to European audiences, most of whom had never encountered an elephant before.

“In the 15th century, there was one elephant in Europe,” Michiel Roscam Abbing, guest curator of the exhibition and author of a new book about Hansken, tells the Times. “In the 16th century, we know of two or three elephants, and the same is true for the 17th century.”

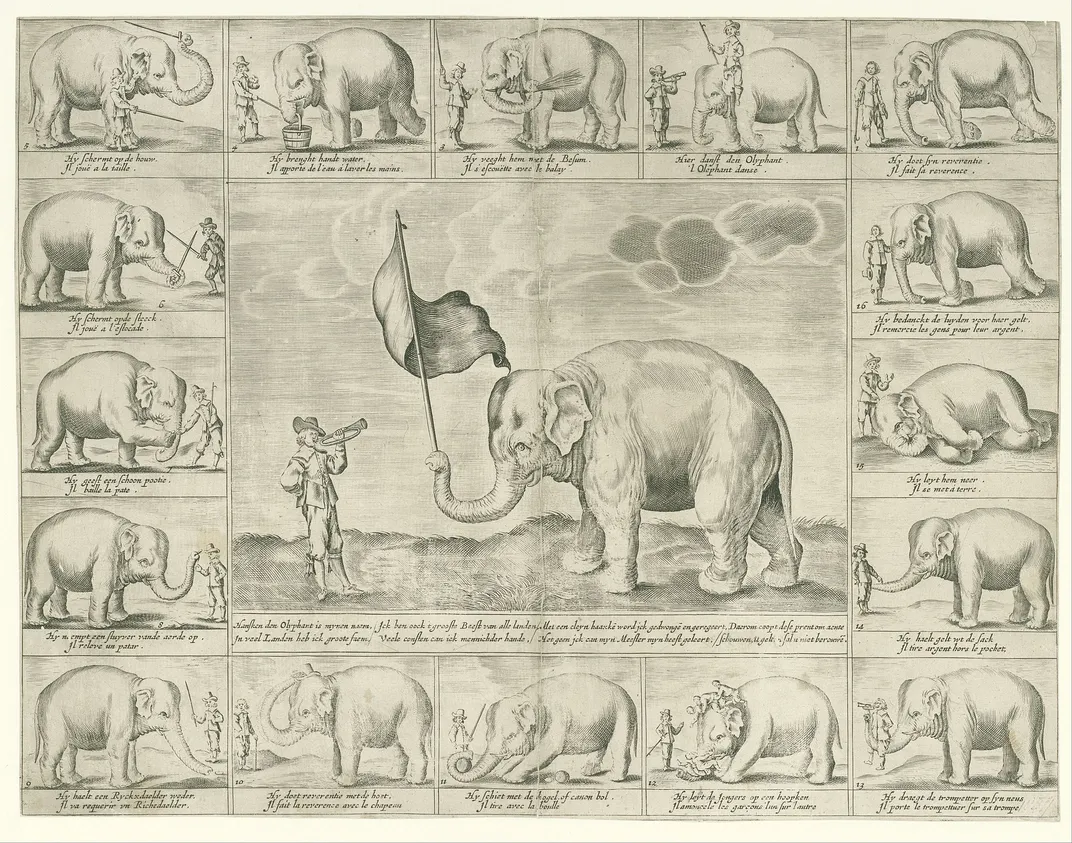

Adding to the public’s fascination with Hansken was surely her ability to perform tricks: van Groenevelt taught her how to hold a sword and fire a gun, among other feats. Intriguingly—and in contrast to other artists who depicted the elephant—Rembrandt did not draw these spectacular features of her performance.

“He was interested in capturing the elephant itself,” Roscam Abbing says.

When she was 25 years old, Hansken collapsed and died in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence. The terrible scene was captured by Stefano della Bella, an artist who happened to witness her final moments. Hansken was young at the time of her death, as Asian elephants can live into their 50s. A postmortem examination revealed abscesses on her feet, and she is thought to have died from an infection. Given Europeans’ lack of knowledge about elephants during this era, Hansken likely didn’t receive proper care and nutrition during her lifetime.

Hansken’s skeleton was exhibited at the Uffizi Gallery and subsequently transferred to the Museo della Specola at the University of Florence. Her remains, in fact, may have served as the basis for the first scientific description of an Asian elephant; the British naturalist John Ray appears to have detailed Hansken’s skeleton in a 1693 book, as Allison Meier reported for Hyperallergic in 2013.

“Although Ray only saw the skeleton of Hansken, the great Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn painted the elephant from life when he saw it in Amsterdam in 1637,” said the researchers in a statement. “This now means that Rembrandt’s paintings and sketches are the original and correct portrayal of the type specimen of an Asian elephant.”

More recently, Hansken’s skull was transported from Italy to Amsterdam, where it is now on view as part of the exhibition.

The new show seeks to encourage visitors to consider Hansken not only as a subject of Rembrandt’s art, but as a living creature who likely endured considerable suffering.

“It’s a very tragic story, actually,” van Sloten tells the Times, “but it’s also fascinating.”

“Hansken, Rembrandt’s Elephant,” is on view at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam through August 29.