At the Harry Truman Library and Museum, Visitors Get to Ask Themselves Where the Buck Stops

Interactive exhibitions pose questions about the decision to drop the nuclear bomb, the Red Scare, Truman’s foreign policy and more

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/cb/4dcbcc50-6ca8-4048-8257-eae5a27b5bca/51262327773_1865f3f00e_o.jpg)

Harry S. Truman, the 33rd President of the United States, assumed the role of commander in chief when President Franklin D. Roosevelt died unexpectedly in 1945, just a few months after being inaugurated for a fourth time. The Missouri native was quickly thrust into one of the most tumultuous periods in U.S. history: In his first four months alone, Truman oversaw the end of World War II in Europe and then the Pacific, signed the United Nations charter, attended the Postdam conference to determine the shape of postwar Europe and made the controversial decision to use nuclear weapons against Japan.

Visitors to Independence, Missouri, just outside of Kansas City, will soon be invited to walk in Truman’s shoes and consider how they would have responded to these events themselves, when the Truman Presidential Library and Museum reopens to the public on July 2, as Canwen Xu reports for the Kansas City Star.

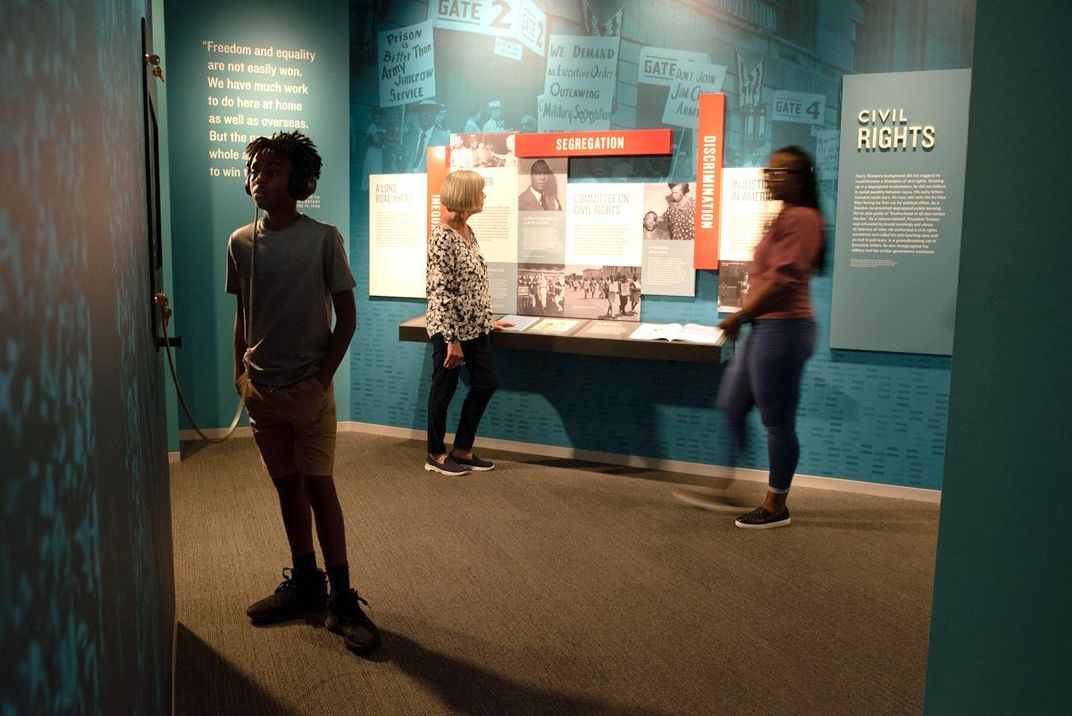

The museum closed two years ago to undergo a $29 million renovation that added 3,000 square feet of new galleries and a new museum lobby, per a statement. Updated, interactive exhibitions tackle Truman's role in World Wars I and II, the Cold War, the aftermath of nuclear warfare in Japan, the beginnings of the American civil rights era and more.

A new permanent exhibition takes visitors through Truman's life, beginning with Truman’s upbringing as a farmer in Independence. One scene recreates the future president’s time as a U.S. Army captain in France during WWI. (Too old for the draft, he enlisted himself at 33.)

Letters from Truman to his wife, Bess, feature in a section entitled “Dear Bess,” which offers insight into the couple’s personal life. Another visitor favorite: the sign that Truman famously kept on his White House desk which reads, “The Buck Stops Here!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/36/6136d4e4-1047-4f22-8bd8-f36795b6e886/truman_58-766-06.jpeg)

“Now you can truly weave through his boyhood into the presidency and beyond,” Kelly Anders, deputy director of the museum, tells the Associated Press’ Margaret Stafford.

In conversation with Laura Spencer for KCUR, director Kurt Graham adds: “I think people will see that, yes, [Truman] was just an ordinary man, but he got launched on an extraordinary journey and had to make decisions that few people in human history have ever had to confront.”

Presidential libraries typically house the archive federally mandated by the Presidential Records Act of 1978. Presidential museums, on the other hand, are privately funded and often tend toward hagiography and overlook scandal, as Ella Morton reported for Atlas Obscura in 2015.

The remodeled Truman library, however, seems to embrace nuance in its treatment of Truman’s infamous decision: giving the order to drop two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on August 6 and 9 of 1945, respectively. The only instance of nuclear force in combat killed more than 200,000 people and left hundreds of thousands of survivors with lingering injuries, cancer and trauma, as Meilan Solly reported for Smithsonian magazine last year.

Truman and his advisors believed that the bombings saved lives by ending the war with Japan. Yet contemporary scholars debate whether the choice was militaristically necessary or ethically justified, and some argue the choice was influenced by anti-Japanese racism, per Khan Academy. Per the Kansas City Star, quotes on the exhibition’s walls offer arguments for and against Truman’s choice, and prompt questions about whether the bomb could have been avoided.

“We’re asking people to not just take what we’re presenting at face value but take that next step and evaluate it,” Cassie Pikarsky, director of strategic initiatives at the Truman Library Institute, tells the Kansas City Star.

The exhibition also encourages viewers to reckon with the human toll of the atom bomb by introducing 12-year-old Sadako Sasaki, a young girl who survived the Hiroshima bombing but died ten years later from leukemia caused by radiation.

As the AP reports, next to the safety plug from the bomb that American forces dropped on Nagasaki, the exhibit features what is believed to be the last origami paper crane that Sasaki folded before she died, donated by her brother. Sasaki spent her final days folding 1,000 paper cranes, a practice that Japanese tradition dictates will grant a person a wish.

Visitors can also consider the implications of Truman’s internationalist foreign policy under a 14-foot-tall fractured “globe,” which represents the hard problems of peace following World War II, per the museum statement. In another room awash in bright-red light, museum-goers are encouraged to take a Red Scare-era questionnaire meant to reveal one’s “communist” sympathies.

The first American president to regularly appear on television, Truman was also one of the most unpopular at the time. He left office in 1953 with a record-low 32 percent approval rating. Yet some historians have reappraised his term in a more favorable light, citing his efforts to desegregate the U.S. Armed Forces as a presidential action that foreshadowed the Civil Rights legislation yet to come.

In a statement, Truman’s eldest grandson Clifton Truman Daniel notes that “[t]he significance of my grandfather’s presidential legacy is more evident than ever.”

“Renovating his library and museum is a fitting way to honor the leading architect of our modern democratic institutions,” Daniel adds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)