Two Darwin Notebooks Quietly Went Missing 20 Years Ago. Were They Stolen?

Staff at Cambridge University Libraries previously assumed that the papers had simply been misplaced in the vast collections

:focal(596x300:597x301)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/5d/655ddee5-e1e1-4e19-8088-a2cc846c9f61/screen_shot_2020-11-24_at_13508_pm.png)

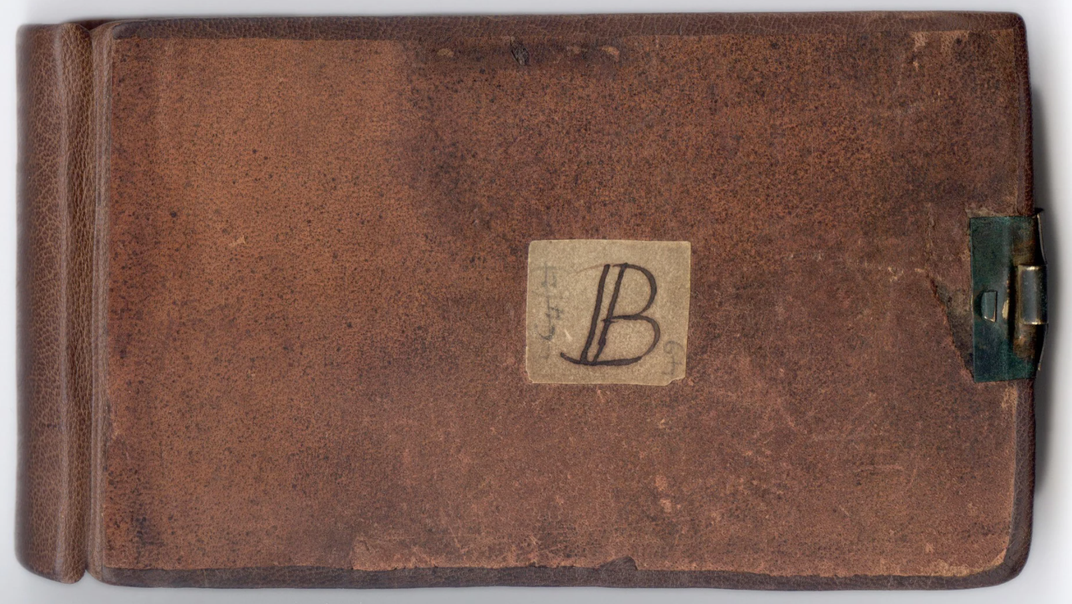

In 1837, a young Charles Darwin wrote “I think” at the top of a page in a small, leather-bound notebook. Then just 28 years old, the naturalist was at home in London following his return from a five-year journey around South America on the H.M.S. Beagle.

Beneath that single phrase, Darwin sketched a spindly diagram of dividing branches—an early illustration of his theory of evolution, which he published formally in the groundbreaking treatise On the Origin of Species more than two decades later.

These pages, which eventually came to reside in the Cambridge University Library collections, represent some of Darwin’s first inklings about the radical idea that all species—including humans—arise and develop through natural selection. With their discovery, Darwin and fellow naturalist Alfred Wallace profoundly changed humans’ understanding of themselves and the natural world. Darwin’s notebooks themselves have been valued at millions of pounds.

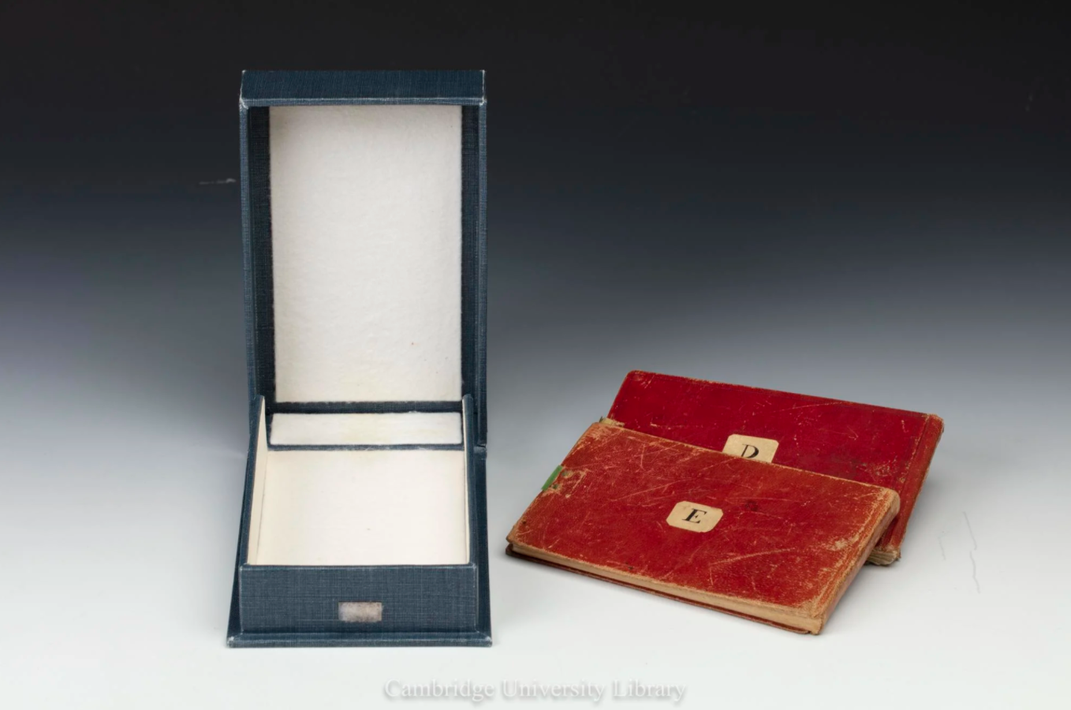

This week, Cambridge made a startling announcement: Two of Darwin’s notebooks, including the one that contains his Tree of Life sketch, have been missing for nearly two decades. The British university, which now believes that the books were stolen, has launched a public appeal to encourage anyone with information about the missing notebooks to reach out to the Cambridgeshire Police or email [email protected].

Local authorities have launched an investigation into the matter and notified Interpol, as well as registering the missing works on the national Art Loss Register, reports the Press Association.

The two texts—Notebook B, which contains the Tree of Life sketch, and Notebook C—were last seen in November 2000, writes Rebecca Jones for BBC News. After staff received an “internal request” to photograph the works, they moved the books from a special manuscript storeroom to a temporary studio established in response to major construction work taking place at the time.

Two months later, a routine check revealed that the manuscripts were gone. The notebooks were officially listed as missing in January 2001, but staff assumed that the books had simply been misplaced in the library’s vast collections, which contain about ten million books and objects, according to Megan Specia of the New York Times.

At the beginning of 2020, a team of experts painstakingly combed through all 189 boxes of the library’s Darwin Archive, per the Cambridge statement. The researchers were unable to locate the lost artifacts, leading the experts to conclude that the notebooks were likely stolen.

“This is heartbreaking,” Jessica Gardner, who started as the library’s director in 2017, tells BBC News. “… We know they were photographed in November. But we do not know what happened between then and the time in January 2001, when it was determined they were not in their proper place on the shelves. And I’m afraid there isn’t anything on the remaining record which tells us anything more.”

The postcard-sized volumes were kept in bespoke blue boxes “about the size of a normal paperback book,” Gardner says in a video appeal. Per the statement, the two journals are known as the Transmutation Notebooks, as Darwin used them to theorize for the first time about how a species might “transmute” from one form to another. The books have both been digitized, but the original texts are considered priceless.

“These notebooks really are Darwin’s attempt to pose to himself the question about ‘where do species come from, what is the origin of species?’” Jim Secord, director of Cambridge’s Darwin Correspondence Project, tells BBC News.

“It’s almost like being inside Darwin’s head when you’re looking at these notebooks,” Secord continues. “… You have the sense of him working through these ideas at great speed and that kind of intellectual energy which I think the notebooks really convey. I’m a fan of James Joyce and it’s always struck me that it’s a bit like Leopold Bloom on steroids. You just get the sense of scientific imagination running really deep.”

The university plans to continue searching its own holdings, including undertaking a complete survey of the library building, per the Press Association. The complete search is expected to take about five years.

“[W]e’re determined to do everything possible to discover what happened and will leave no stone unturned during this process,” Gardner says in the statement. “… Someone, somewhere, may have knowledge or insight that can help us return these notebooks to their proper place at the heart of the U.K.’s cultural and scientific heritage.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/91/7a91ff81-f741-4b2c-8ca2-ec4eb45f4e14/darwinstreeoflifesketch-1200x1909.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)