Two New Exhibitions Celebrate a Long-Lost Painting

The “Tower of the Blue Horses” is gone, but not forgotten

World War II killed millions, leaving behind a shattered landscape and a population decimated by the terrors of Nazi Germany. But people and cities weren’t the Nazis’ only victims. So was art. Since 1945, people have been searching for the artistic masterpieces plundered by the Nazis and spread around the world—and now, contemporary artists are reimagining one of those lost masterworks.

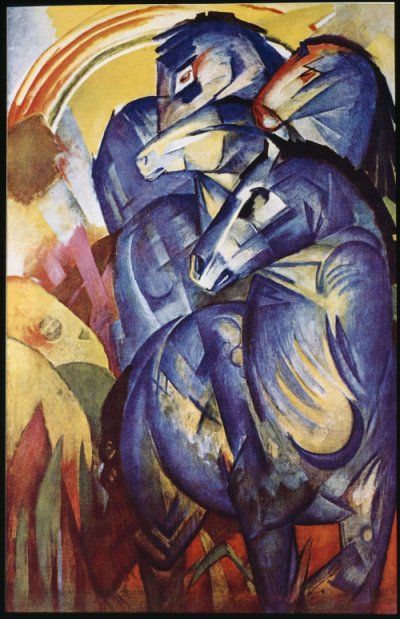

The oil painting is called “Der Turm der blauen Pferde” (“The Tower of Blue Horses”), and its history is as shocking as its bold shades of blue. It was painted by Franz Marc, a German artist, in 1913. Marc helped found one of the main movements of German Expressionism, a group called Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), along with Wassily Kandinsky whom he had met after he joined the "New Artists' Association of Munich" in 1901. The friends shared the same views of art as a means for personal and spiritual expression, Amanda Fiegl writes for Smithsonian.com. After the New Artists' Association rejected one of Kandinsky's paintings in 1911, the duo decided to leave and start a group of their own.

True to form, The Blue Rider's members were interested in conveying the spiritual, often using musical references in their work, and the group's symbol, a blue horse, became part of many of the movement’s most important works. Marc in particular loved to paint horses and incorporated them into many of his most famous paintings.

Marc was conscripted into World War I despite his own utopian ideals and hatred of war. He died at the Battle of Verdun—ironically, while mounted on a horse. But his influential work lingered. His huge tower of horses was displayed in both Munich and Berlin and revered as an example of bold Expressionism until the Nazis came into power in 1933. Hitler, himself a painter, abhorred modern art and dubbed it “degenerate,” and the painting was seized and shown in the regime’s 1937 exhibition of art they claimed went against traditional German values.

This sparked a protest. Marc had died for his country, his friends insisted, and the League of German Army Officers agreed. They lodged a protest and Marc’s art was removed from the exhibition. That’s where things get dicey. The painting was moved to a warehouse, then transferred to Nazi leader Herrmann Göring. It was spotted on and off after World War II, but after 1949, it could no longer be located, according to the National Museums in Berlin. It has never been recovered. The only trace that remains is a tiny study for the painting—no substitute for the real thing.

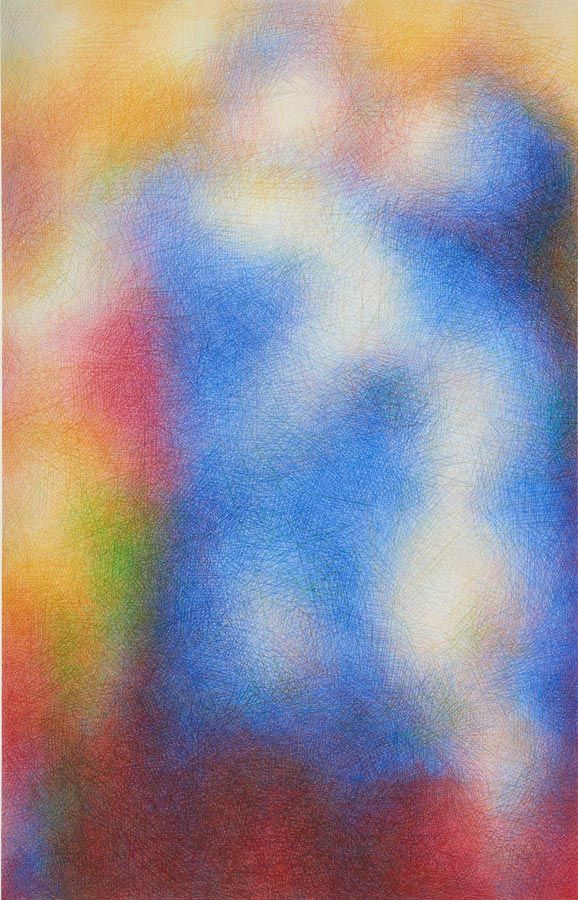

Now, the Haus am Waldsee in Berlin and The Pinakotheken in Munich are hosting paired shows in which contemporary artists reimagine the painting. The Berlin show deals with the circumstances of the painting’s theft and loss; the Munich show with the postcard-sized study. Appropriately, both shows are entitled MISSING. The revisitation is a testament to the hold a disappeared piece of art can still have on the imagination—and the tragic losses of the Nazi era that may never be resolved.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)