The Victorian Tattooing Craze Started With Convicts and Spread to the Royal Family

A new series of data visualizations offers insights on the practice’s historical significance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/42/2742c912-65f4-4887-9e6b-552b0b4f6cb2/tattoos.jpg)

The 75,688 tattoos cataloged in the Digital Panopticon database of Victorian era convicts depict a dizzying array of subjects. A “habitual criminal” named Charles Wilson, for instance, boasted body art featuring a bust of Buffalo Bill, a heart and the name “Maggie.” One Martin Hogan had tattoos of a ring, a cross and a crucifix. Other popular designs documented via the online portal include anchors, mermaids, the sun, the stars, loved ones’ initials, decorative dots, weapons, animals, flags and nude figures.

Per a November 2018 blog post, the researchers behind Digital Panopticon—a sweeping collaborative project that traces the lives of some 90,000 criminals convicted at the Old Bailey courthouse and imprisoned in Britain or Australia between 1780 and 1925—set out to study convict tattoos in hopes of better understanding the practice of tattooing’s historical significance.

Prisoners’ tattoos weren’t symbols of criminal affiliation or “bad repute” as commonly thought, report project investigators Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alker for the Conversation. Instead, the designs “expressed a surprisingly wide range of positive and indeed fashionable sentiments.”

“Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own,” the researchers write. “As a form of ‘history from below,’ they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.”

Although the survey centered on the 58,002 convicts whose tattoos are described in surviving records, the team also found that tattooing was a “growing and accepted phenomenon” in the wider cultural sphere of Victorian England, according to Shoemaker and Alker.

Far from appearing solely on the bodies of convicts, soldiers and sailors, tattoos became increasingly fashionable over the course of the Victorian era. In 1902, a British magazine touted the “slight pricking” of the tattoo needle as so painless that “even the most delicate ladies make no complaint.” By the turn of the 20th century, unskilled workers, engineers and royals alike were all sporting body art. As Ros Taylor reported for BBC News in 2016, the future George V got a tattoo of a blue-and-red dragon during an 1881 trip to Japan, and his father, Edward VII, commissioned a tattoo of a Jerusalem Cross during a pilgrimage.

The Digital Panopticon team used data-mining techniques to extract information on tattoos from broader descriptive records of criminals imprisoned in both Britain and Australia, where an estimated 160,000 convicts were sent between 1788 and 1868. According to the project page, detailed physical descriptions of prisoners were commonly recorded, as these identifying features could be used to track down escaped convicts and repeat offenders.

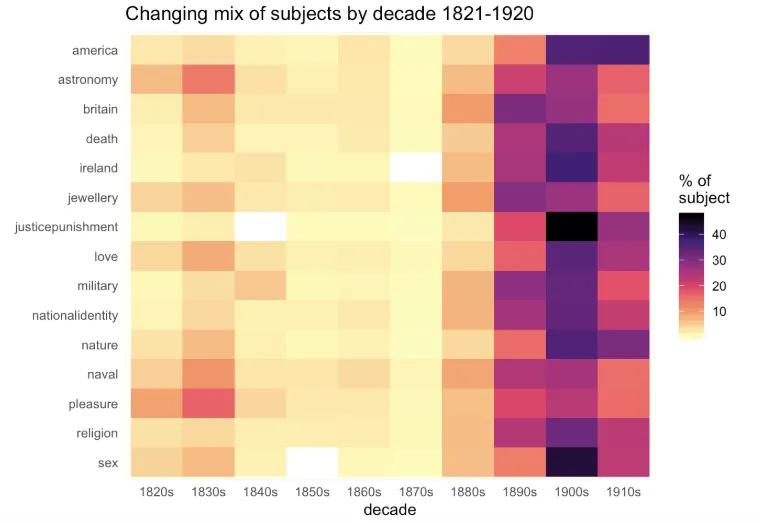

After extrapolating the relevant data, the investigators divided tattoo descriptions into four subcategories: designs (such as anchors and rings), written words or letters, body part(s), and subjects (the list runs the gamut from national identity to astronomy, death, pleasure, religion and nature).

Using these data points, the team created a unique set of visualizations exploring such topics as changing tattoo trends over time, males’ versus females’ chosen tattoo subjects, and correlations between subjects. Between 1821 and 1920, naval themes, religious symbols and tokens of love topped the tattoo chart, while images of justice and punishment, America, and sex were rarely inked. The most popular tattoo location was the arm, followed by the elbow, and the most popular tattoo subjects were names and initials.

As Shoemaker and Alker write for the Conversation, convicts’ tattoos were less concerned with “expressing a criminal identity” than inscribing the body “in much the same way” as modern tattoos.

“In their images of vice and pleasure some convicts may have signaled an alternative morality but for most,” the researchers conclude, “tattoos simply reflected their personal identities and affinities—their loves and interests.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)