You Can Now Explore an Unseen Trove of Franz Kafka’s Personal Papers Online

The National Library of Israel has digitized a rare collection of the “Metamorphosis” author’s letters, drawings and manuscripts

:focal(511x371:512x372)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/5c/ac5c5910-578b-46b0-8b03-6a0870289b78/_118692614_retouched_1-postcards-from-kafka-to-brod-from-the-literary-estate-of-max-brod-national-library-of-israel.jpeg)

During his lifetime, the celebrated Czech Jewish author Franz Kafka penned an array of strange and gripping works, including a novella about a man who turns into a bug and a story about a person wrongly charged with an unknown crime. Now, almost a century after the acclaimed author’s death, literary lovers can view a newly digitized collection of his letters, manuscripts and drawings via the National Library of Israel’s website.

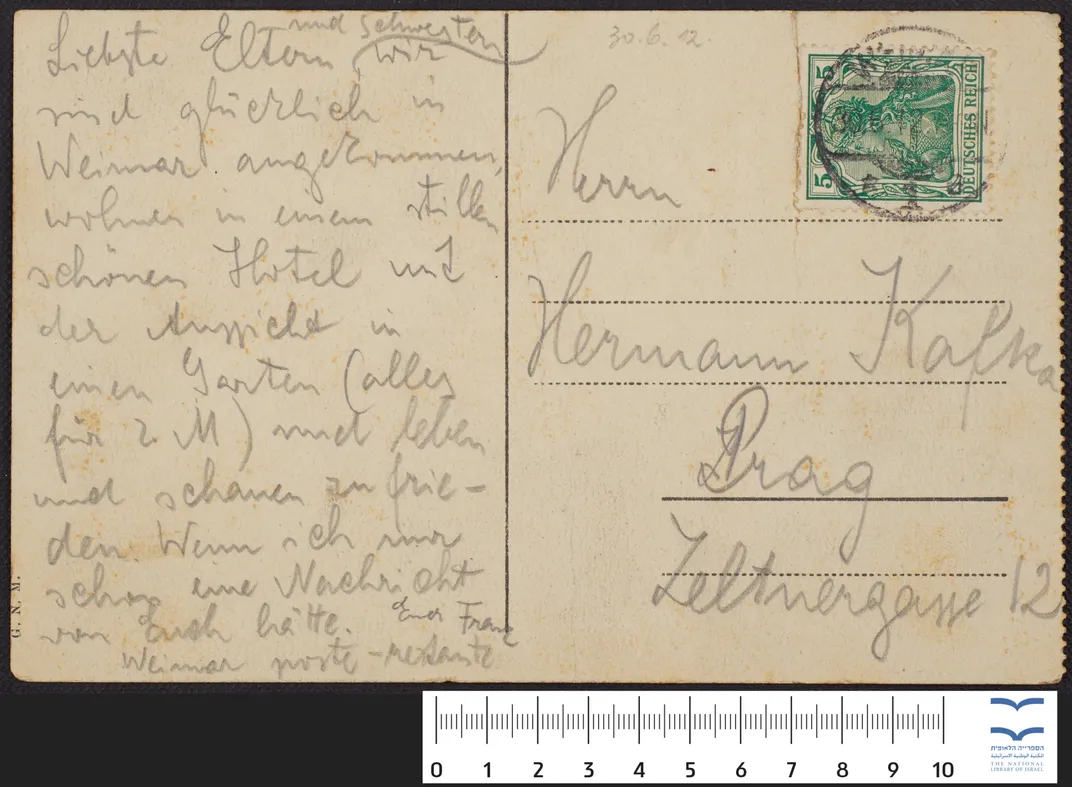

As Agence France-Presse (AFP) reports, the collection contains around 120 drawings and more than 200 letters owned by Max Brod, a friend and fellow writer who served as Kafka’s literary executor. Instead of destroying the author’s papers as he had requested, Brod chose to publish and preserve them.

Per a blog post, the library acquired the archive after a protracted legal battle with the family of Brod’s secretary, Esther Hoffe, who gained possession of the papers following his death in 1968. Between December 2016 and July 2019, staff transferred the entirety of Brod’s collection—much of which had been stashed in safety deposit boxes—to the Jerusalem-based library.

“The Franz Kafka papers will now join millions of other items we have brought online in recent years as part of our efforts to preserve and pass down cultural assets to future generations,” says Oren Weinberg, the library’s director, in a statement quoted by the Jerusalem Post’s Gadi Zaig. “We are proud to now offer free, open access to them for scholars and millions of Kafka fans in Israel and across the globe.”

Highlights of the collection include Kafka’s letters to Brod, fiancée Felice Bauer and theorist Martin Buber, as well as a draft of the short story “Wedding Preparations in the Country,” a journal documenting the writer’s trips to Switzerland and excerpts from the novel The Castle.

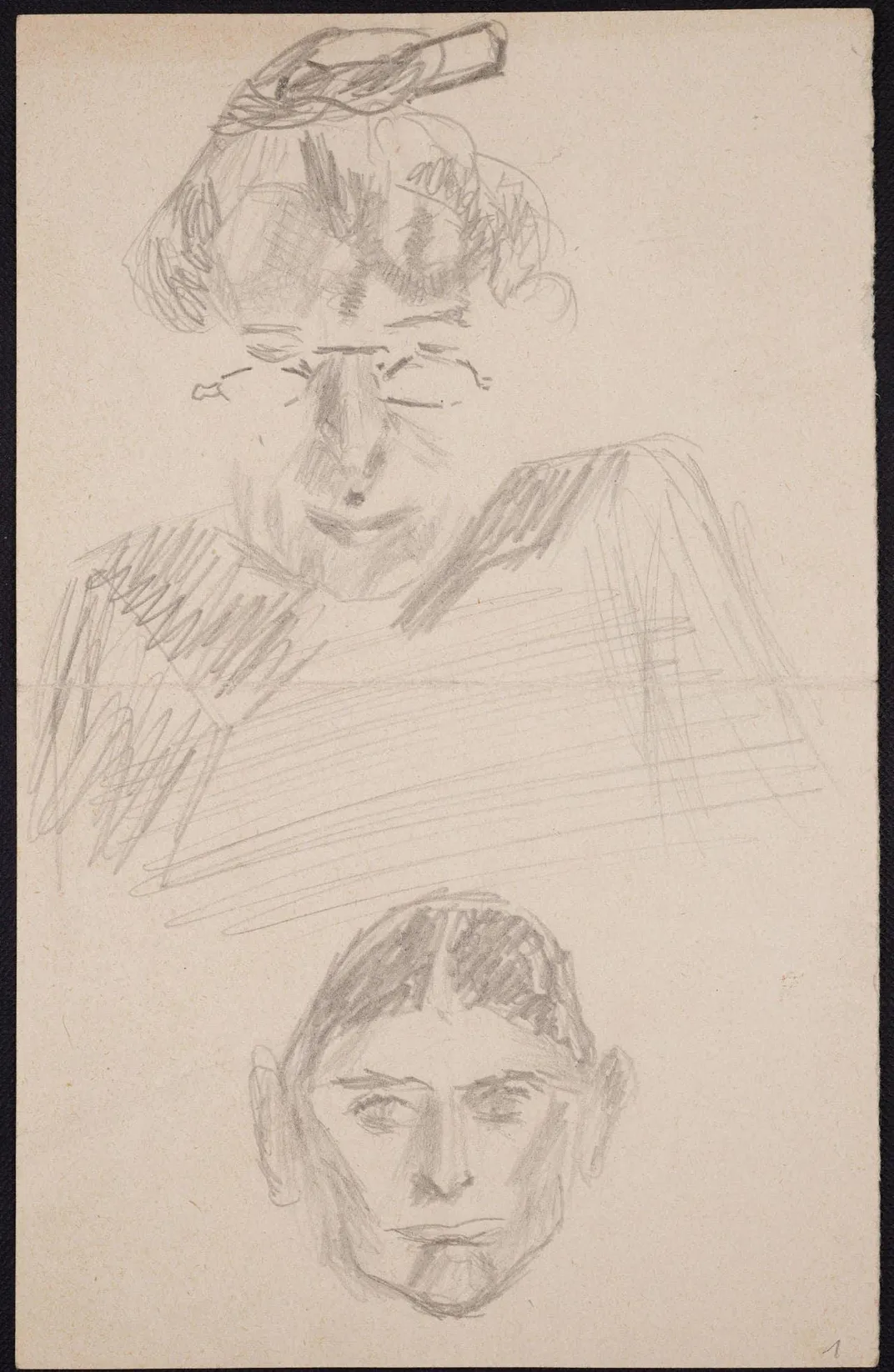

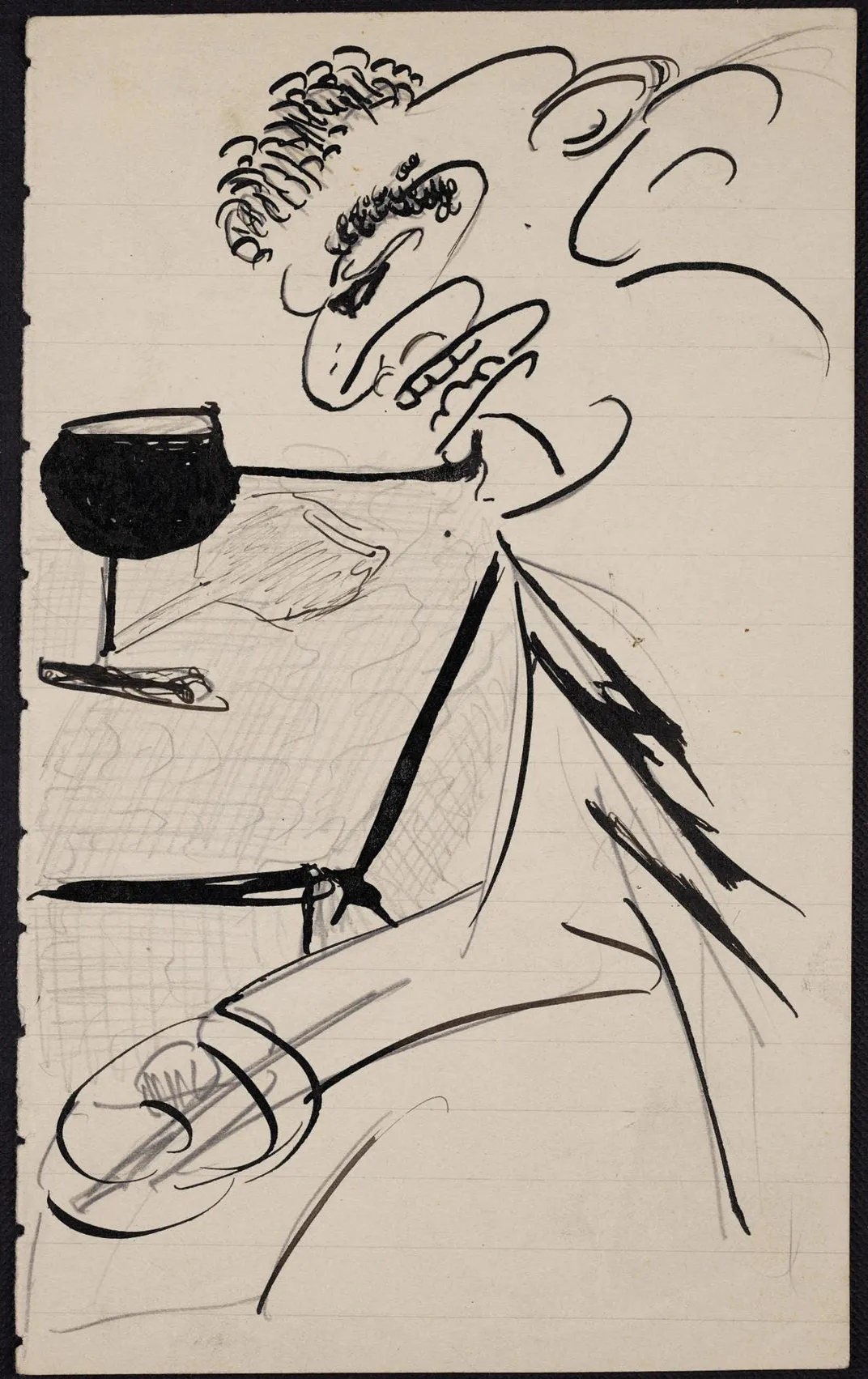

The archive’s drawings, which date to between 1905 and 1920, range from self-portraits to pictures of other people and quick sketches, reports Ofer Aderet for Haaretz. One is an intimate portrayal of Kafka’s mother, who wears her hair in a high bun and dons small, oval-shaped spectacles. Another ink drawing titled Drinker shows an irate-looking man slumped in front of a glass of wine.

Though the majority of the materials have already been published, a select few were previously unknown to researchers.

“We discovered unpublished drawings, neither signed nor dated, but that Brod had kept,” curator Stefan Litt tells AFP.

He adds, “The big surprise we received when we opened these documents was his blue notebook, in which Kafka wrote in Hebrew, signing ‘K,’ his usual signature.”

Born in Prague in 1883, Kafka had a troubled childhood that deeply influenced his work. His two older brothers died in infancy, leaving him the eldest of four surviving children. The young writer also had a strained relationship with both of his parents: Per Encyclopedia Britannica, he said that his father, Herman, was emotionally abusive and prioritized material success and social status above all else.

Among the newly digitized papers is a scathing, 47-page letter to Herman; never delivered, it describes Kafka as a “timid child” who cannot have been “particularly difficult to manage.”

The author continues, “I cannot believe that a kindly word, a quiet taking by the hand, a friendly look, could not have got me to do anything that was wanted of me.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/45/3e4583c8-2d0a-4106-8f3a-e507213292b6/1024px-kafka.jpeg)

Kafka met Brod while studying law in Prague. His university years inspired many of his later works, which explored such topics as alienation and unjust punishment—themes the author grappled with both personally and in his career.

In 1924, Kafka died at age 40 after a years-long struggle with tuberculosis. In his will, the author implored Brod to destroy his manuscripts, but his friend refused to do so. Instead, Brod collected, edited and published many of Kafka’s iconic texts, including The Trial, Amerika and The Castle.

When Brod immigrated to Palestine in March 1939, he took most of Kafka’s papers with him. According to the library, Brod relinquished the majority of the documents to Kafka’s heirs—the children of one of his sisters—in 1962; this collection is now housed at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England. Though Brod’s will directed his secretary, Hoffe, to place the remaining materials in a public archive, she defied his wishes by selling off items from the trove piecemeal.

As AFP notes, the “multi-country legal soap opera” that ensued was fittingly “Kafkaesque.” But decades later, the library’s efforts to reunite the collection have finally proven successful.

Kafka, for his part, “did not attach much significance to his personal archive,” writes Litt in a blog post. “… Any thought of his personal papers’ importance was foreign to him. One can assume that he did not foresee either the monetary value or near ‘sacred’ aura attributed to each handwritten item today.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)