Viking Runestone May Trace Its Roots to Fear of Extreme Weather

Sweden’s Rök stone, raised by a father commemorating his recently deceased son, may contain allusions to an impending period of catastrophic cold

:focal(426x304:427x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/c0/b8c0445b-304e-4ac1-be33-fb3d96112b33/96cfc0b551855d14_800x800ar.jpg)

Sometime in the early ninth century, an anxious Viking mourning the death of his son began to worry that winter was coming. To cope, he channeled his fears into a wordy essay he then painstakingly chiseled onto the surface of a five-ton slab of granite.

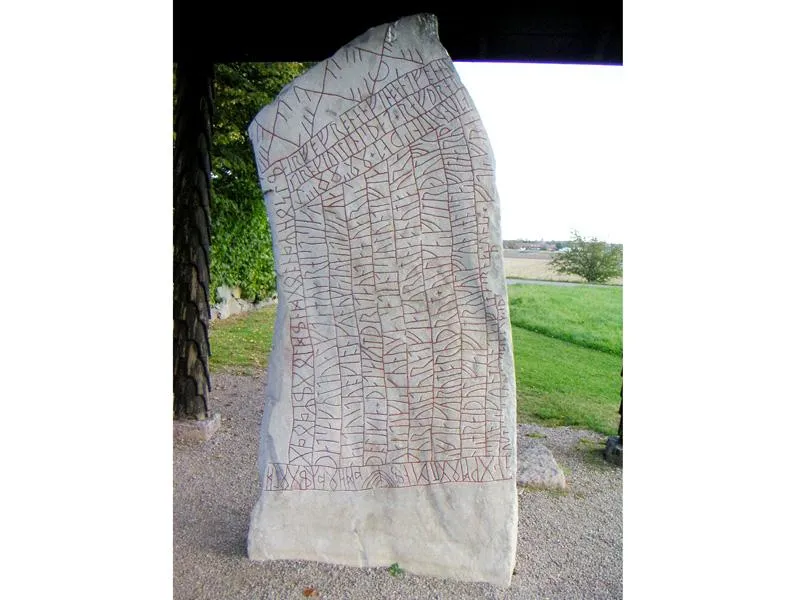

This unusual origin story may be behind the creation of Sweden’s Rök stone, an eight-foot-tall monolith whose enigmatic etchings—which comprise the world’s longest known runic inscription—have puzzled researchers for more than a century. Writing this week in Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies, a team led by Per Holmberg, a scholar of Swedish language at the University of Gothenburg, argues that its text, interpreted as a grieving father’s eulogy of his dead son, may also contain allusions to a broader crisis: an impending period of extreme cold.

These new interpretations don’t refute the paternal tribute or diminish the tragedy of the death itself. But as the authors explain, it may widen the scope of the stone’s broader message.

The Rök stone’s five visible sides are speckled with more than 700 runes, most of which are still intact. The monolith’s text hints that it was raised by a man named Varinn around 800 A.D. to commemorate his recently deceased son Vāmōðʀ. The runes also mention a monarch many suspect was Theodoric the Great, a sixth-century ruler of the Ostrogoths who died in 526, about three centuries prior.

The study’s findings, which drew on previous archaeological evidence, might help make sense of this somewhat anachronistic reference. Shortly after Theodoric’s reign ended, reports Agence France-Presse, a series of volcanic eruptions appear to have plunged what’s now Sweden into a prolonged cold snap, devastating crop fields and prompting starvation and mass extinctions.

Between 536 and 550, as much as half the population of the Scandinavian Peninsula may have died, fueling a climatic cautionary tale that likely lingered for many decades after, according to Michelle Lim of CNN. Fittingly, writes Becky Ferreira for Vice, the stone’s inscriptions make reference to “nine generations”—enough to span the 300-year gap.

Shaken by tales of this sixth-century crisis, Varinn may have feared the worst when he witnessed another unnerving event around the time of the Rök stone’s creation. Between the years 775 and 810, three anomalies occurred: a solar storm, an especially cool summer, and a near-total solar eclipse, each of which could have been mistaken as a harbinger of another prolonged cold spell, says study author Bo Graslund, an archaeologist at Uppsala University, in a statement.

To make matters worse, eclipses and intense winters both feature prominently in Norse mythology as potential signs of Ragnarök, a series of events purported to bring about the demise of civilization. Varinn’s concerns, it seems, were more than understandable.

A liberal read of some of the text’s imagery could fall in line with a climatic interpretation as well, the researchers argue. A series of “battles” immortalized on the stone, for instance, may have been a reference not to a clash between armies, but the chaos of climate change.

Plenty of the Rök stone’s mysteries remain unsolved, and future work could still refute this new interpretation. But if Varinn truly did have climate on the brain, his fears about the fragility of the world still ring eerily true today: When severe enough, global change can truly be a “conflict between light and darkness, warmth and cold, life and death.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)