Visit the Manuscript of ‘Jane Eyre’ in New York

The handwritten novel is in the United States for the first time—along with an exhibition of artifacts from Charlotte Brontë’s brief and brilliant life

How did Charlotte Brontë go from scribbling in secret to one of England’s (and literature’s) most famous names? Look for the answer in a passage in Jane Eyre, in which her famously plain heroine tells her husband-to-be that she is a “free human with an independent will.” That bold declaration is at the center of a new exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York—one that celebrates the author’s 200th birthday with a look at the forces that turned her into a writer.

Brontë has been at the center of literary legend since her first published novel, Jane Eyre, appeared under a pseudonym in 1847. The book was immediately loved and loathed for emotions that flew in the face of convention and courtesy, and the identity of its author became a much-contested question. But even after Brontë was discovered to be the person behind the pen name Currer Bell, myths about her childhood, her family members and the atmosphere in which she became an author have persisted.

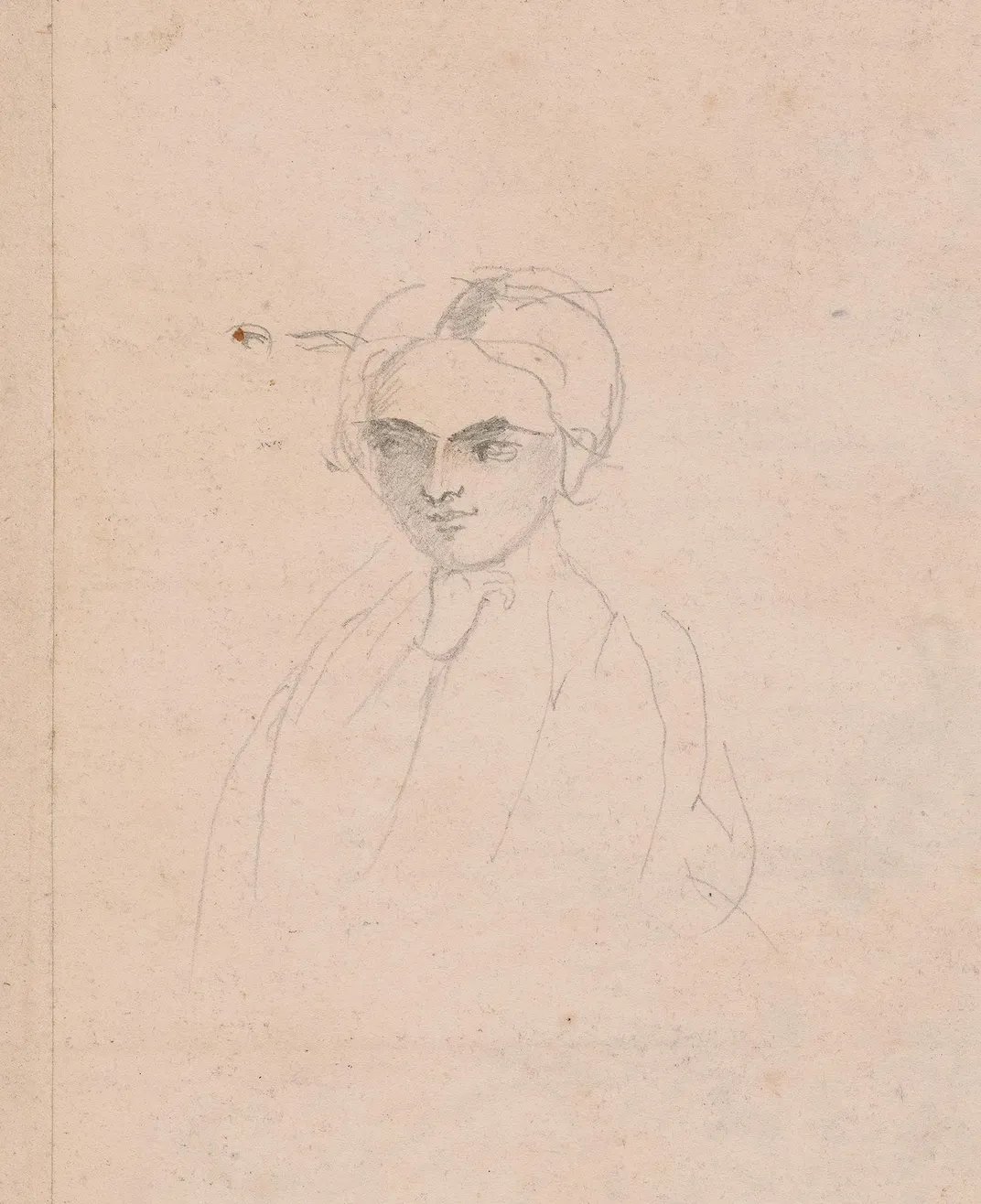

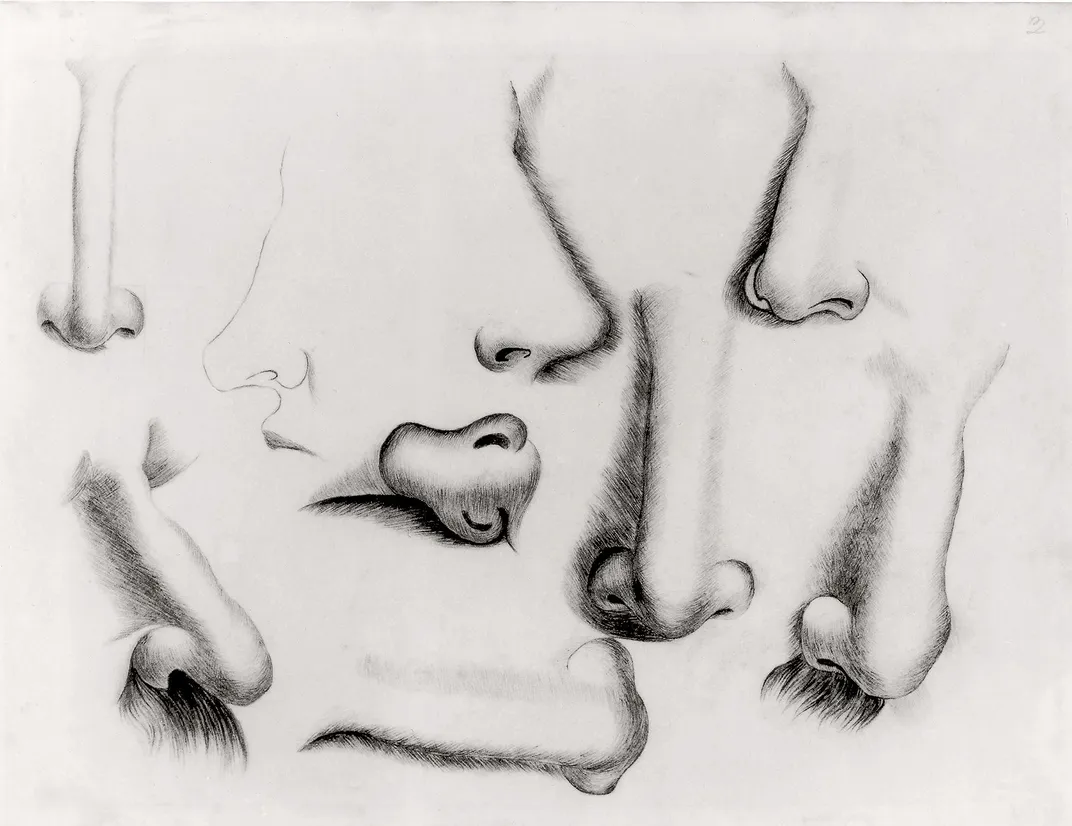

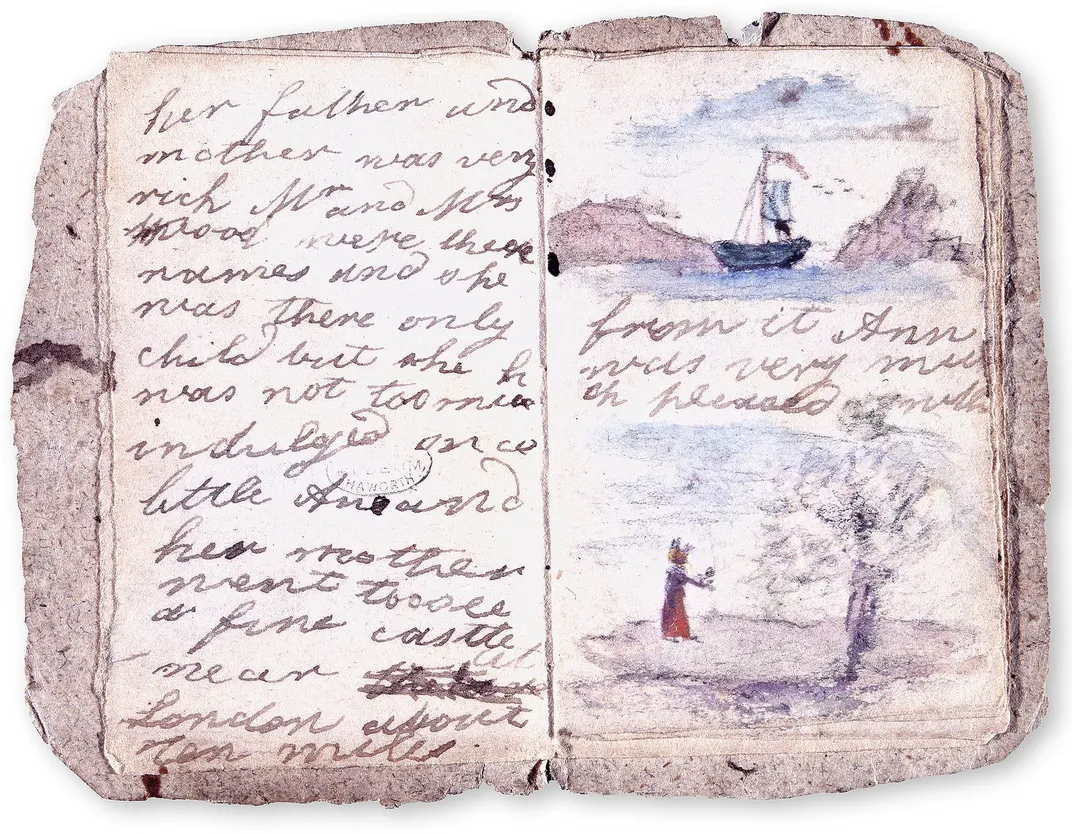

The popular image of the Brontë sisters and their brother Branwell—all of whom died before they turned 40—has long been one of Gothic isolation and tragic pathos. But those ideas are far from true, and the Morgan’s exhibition Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will grounds Charlotte’s brief life in objects from her everyday world. From miniature manuscripts she wrote as a child to her drawings, paintings, letters and clothing, the exhibition is full of clues as to how a parson’s daughter living in Yorkshire could become a worldly and bold author.

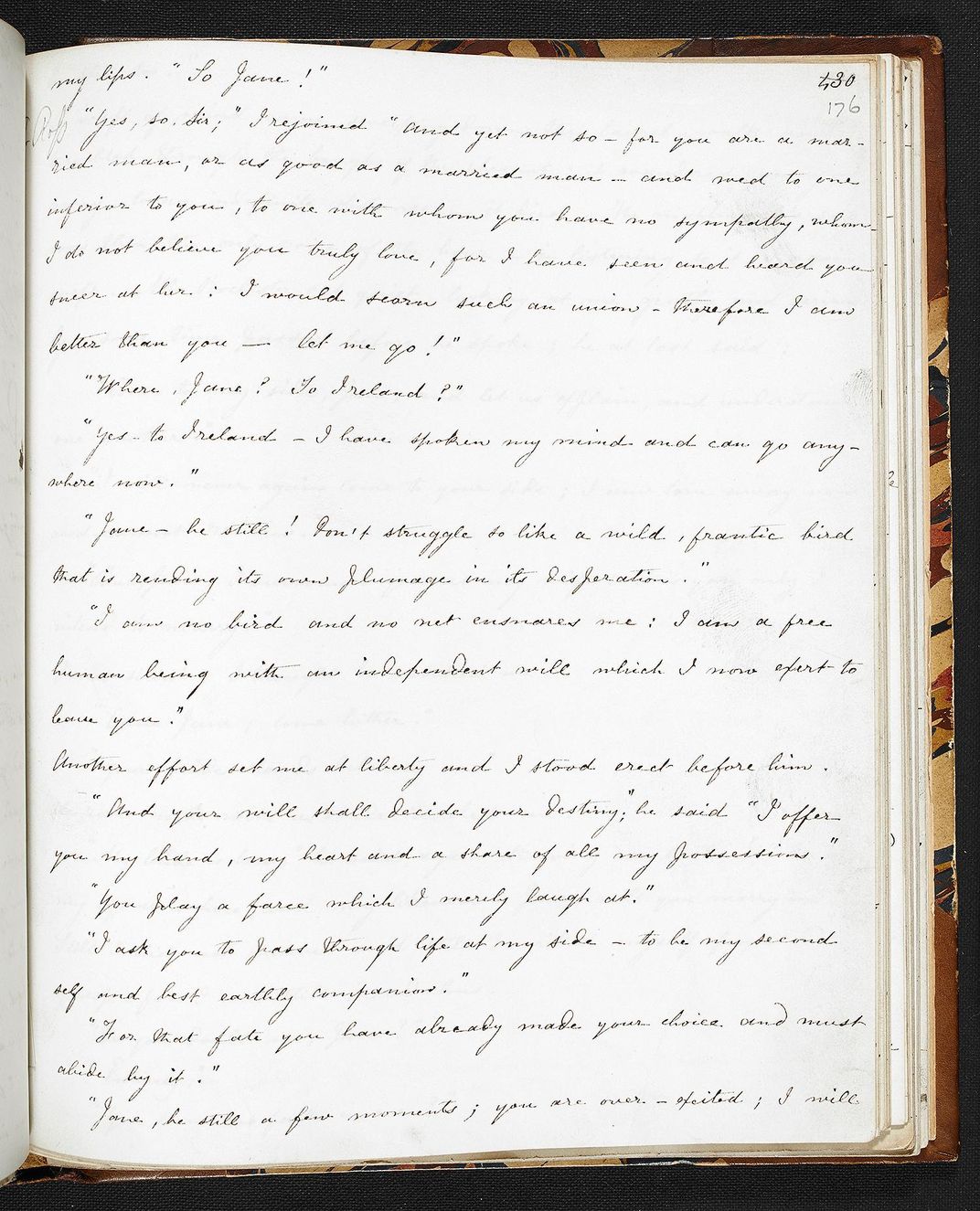

At the center of the exhibition is a handwritten manuscript of Jane Eyre, Brontë’s most famous novel, which is in the United States for the first time. It is open to the passage in which its heroine, a poor and plain governess, reminds her would-be lover that “I am a bird, and no net ensnares me.” She refuses to marry Edward Rochester, a wealthy landowner, unless he accepts her as an equal and not a subordinate. That fiery sentiment was echoed by Brontë herself. In an era in which women of her station were expected to be governesses or teachers, she aspired to be a novelist. And even when her work gained fame, she challenged her readers to judge her by her output and not her gender.

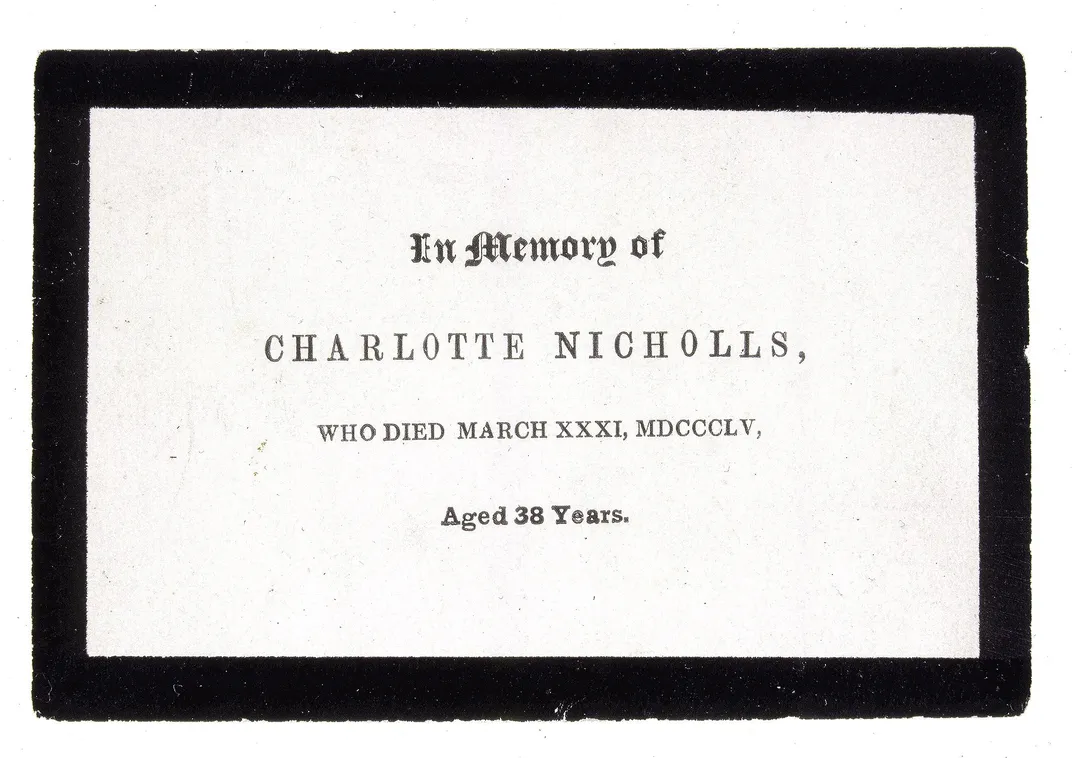

Though the exhibition features documents from some of Charlotte’s most triumphant moments, it also contains echoes of tragedy. In 1848 and 1849, her three surviving siblings, Branwell, Emily and Anne, died within eight months of one another. Alone and stripped of her best friends and literary co-conspirators, Charlotte grappled with depression and loneliness. Visitors can read letters she wrote informing friends of her irrevocable losses, handwritten on black-edged mourning paper.

In the 161 years since Charlotte’s own early death at age 38, her literary reputation has only grown larger. But that doesn’t mean she was large in actual stature—the diminutive author stood less than five feet tall, as demonstrated by a dress in the exhibition. She may have been physically tiny, but her larger-than-life genius lives on in the objects she left behind. The exhibition runs through January 2, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)