DNA Analysis Debunks the Rumor That Rudolf Hess Was Replaced by a Doppelgänger

For decades, rumors have swirled that the Nazi official imprisoned by the British was actually an imposter

:focal(1505x649:1506x650)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/43/6b4371a7-42bf-4fb2-a4de-94ce567a7cff/gettyimages-3286383.jpg)

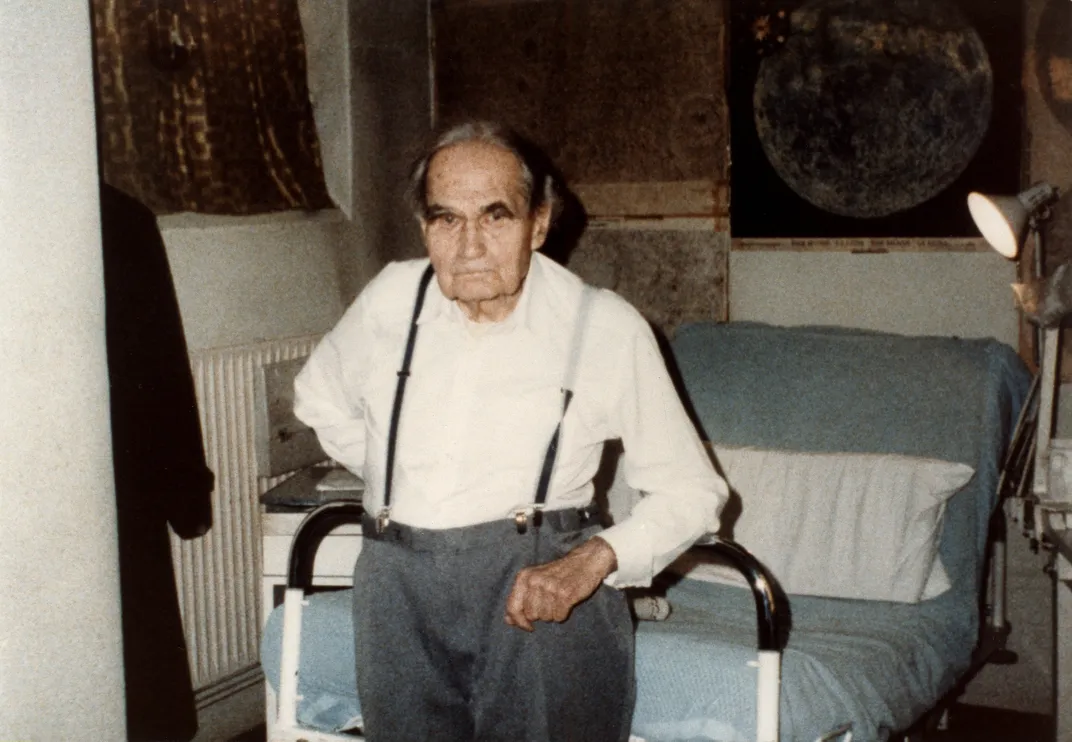

In May 1941, the deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler set off on a dangerous solo flight to Scotland, where he hoped to broker a peace treaty with Britain. Rudolf Hess’ strange and ill-advised mission very quickly began to unravel. His plane ran out of fuel, for one, forcing him to land in a field several miles from his destination. And instead of finding British officials sympathetic to his cause, Hess was, unsurprisingly, whisked away into prison. After he was convicted and given a life sentence during the post-war Nuremberg trials, Hess spent 46 years in the Spandau prison in Berlin. He died there in 1987, reportedly by suicide, though some insist that he was murdered to stop him from revealing wartime secrets.

This is not, in fact, the strangest conspiracy theory that shrouds Hess’ tortured legacy. For decades, rumors have swirled that the man who was captured in Scotland, convicted at Nuremberg and imprisoned in Spandau was not Hess at all, but an imposter. But, as Rowan Hooper of New Scientist reports, a recent genetic analysis may finally put this notion to rest.

Speculation about a Hess doppelgänger has not been confined to fringe theorists. Franklin D. Roosevelt reportedly believed that Spandau prisoner number 7 was an imposter, as did W. Hugh Thomas, one of the doctors who tended to the man claiming to be Hess. Thomas cited a number of factors to support his hypothesis: the prisoner’s refusal to see his family, his apparent lack of chest scars that would have been consistent with an injury Hess sustained during WWI, the absence of a gap between his teeth that can be seen in earlier photos of Hess.

Proponents of the imposter theory believe, according to a new study published in Forensic Science International Genetics, that the doppelgänger served to cover up Hess’ murder by either German or British intelligence. And it is possible to understand why people might search for an alternative explanation to the bizarre narrative of Hess’ wartime jaunt to Britain, which seemed to suggest he believed “you could plant your foot on the throat of a nation one moment and give it a kiss on both cheeks the next,” as Douglas Kelley, an American psychiatrist who examined Hess, once put it.

Hess’ motivations for flying to Scotland remain opaque, but the new forensic analysis suggests it was no double who ended up in Spandau. In the early 1980s, study co-author and U.S. Army doctor Phillip Pittman took a blood sample from Hess as part of a routine check-up. Pathologist Rick Wahl, another of the study’s co-authors, then hermetically sealed some of the sample to preserve it for teaching purposes. This proved to be a fortuitous decision. After Hess’ death, his gravesite in the Bavarian town of Wunsiedel became a rallying point for neo-Nazis. So in 2011, his remains were disinterred, cremated and scattered at sea.

As part of the new study, researchers extracted DNA from the preserved blood sample and, in the hopes of establishing a familial line, embarked on the difficult task of tracking down one of Hess’ living relatives.

“The family is very private,” lead study author Sherman McCall tells Hooper. “The name is also rather common in Germany, so finding them was difficult.”

The researchers were eventually able to locate one of Hess’ male relatives, whose identity has not been revealed. When analyzing the DNA of the two men, the team paid particular attention to the Y chromosome, which is passed from fathers to sons. “Persons with an unbroken paternal line display the same set of DNA markers on the Y chromosome,” Jan Cemper-Kiesslich, another of the study’s authors, explains in an interview with the Guardian’s Nicola Davis.

This genetic investigation yielded telling results: There was found to be a 99.99 percent likelihood that the two individuals were related.

“We are extremely sure that both samples [originate] from the same paternal line,” Cemper-Kiesslich tells Davis. “The person the slide sample was taken from indeed was Rudolf Hess.”

The new study demonstrates how DNA analysis can be of vital use to historical research, particularly when it comes to the “unambiguous identification of mortal remains of persons and families of recent historical relevance,” as the study authors write. Of course, it also suggests that Hess doppelgänger conspiracy theories really are just that—theories, with no grounding in historical truths.