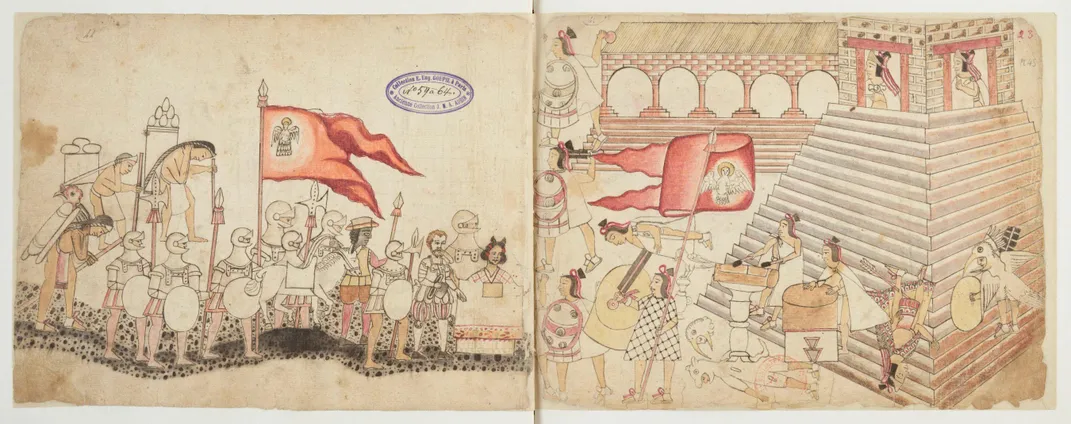

In 1519, as Spain began brutally ravaging Mesoamerica, conquistador Hernán Cortés encountered the secret weapon who would help seal his victory: La Malinche. An enslaved Aztec girl who had been sold across the Yucatán Peninsula, Malinche was skilled at speaking both Yucatec and Nahuatl—Maya and Aztec languages, respectively. Drawing on her interpretation ability and navigation experience, she made herself essential to Cortés, providing him with access to envoys and steering his men through the unfamiliar landscape.

Few historical records of Malinche’s life exist. None are written in her own words. But in the centuries following Spain’s colonization of present-day Latin America, many observers have wrestled with her role in Cortés’ conquest. Now, reports Erika P. Bucio for El Norte, a new exhibition at the Denver Art Museum (DAM) in Colorado is set to interrogate Malinche’s legacy through an artistic lens.

“In examining and presenting the legacy of Malinche from the 16th century through today, we hope to illuminate the multifaceted image of a woman unable to share her own story, allowing visitors to form their own impressions of who she was and the struggles she faced,” says curator Victoria I. Lyall in a statement.

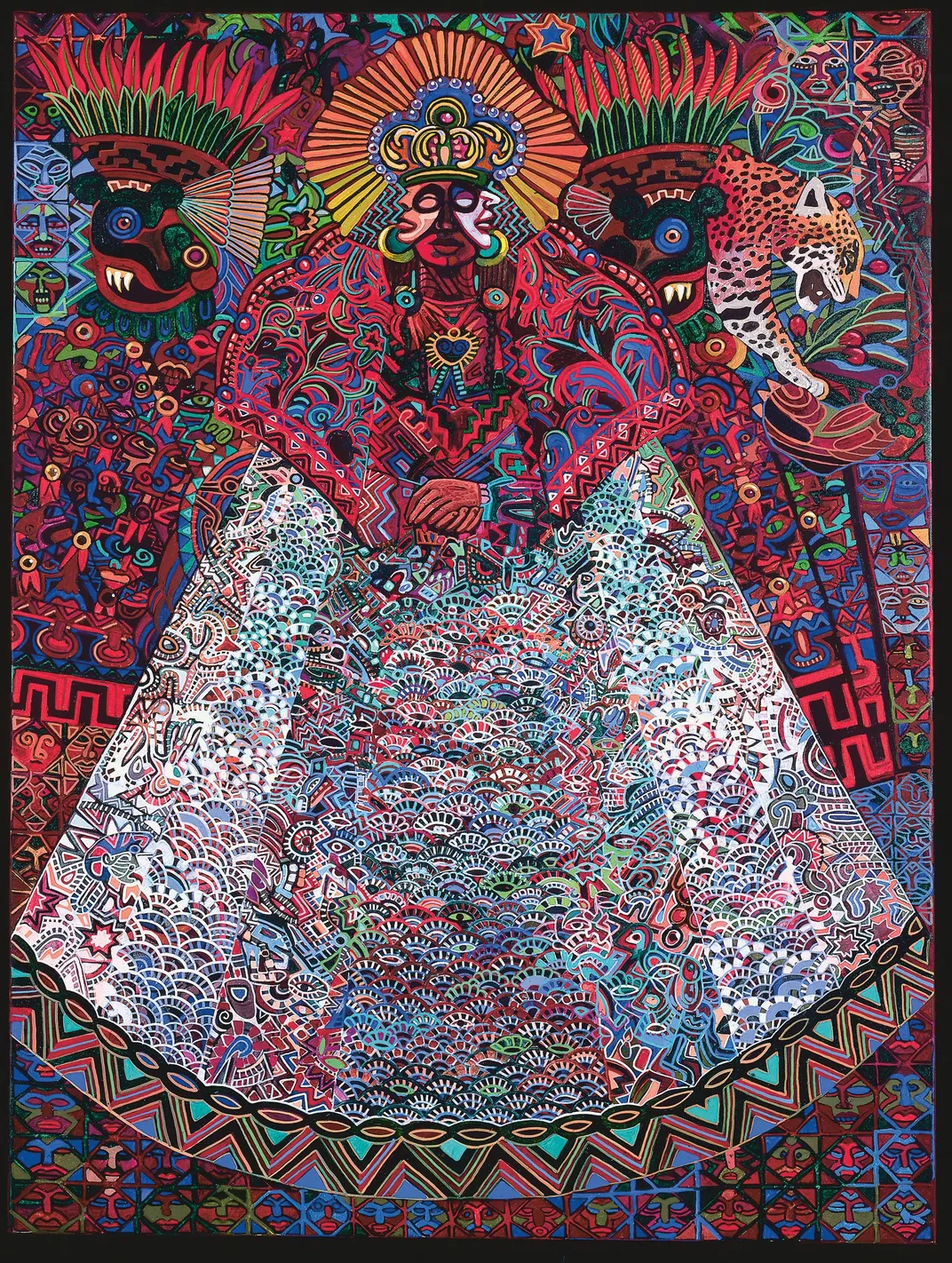

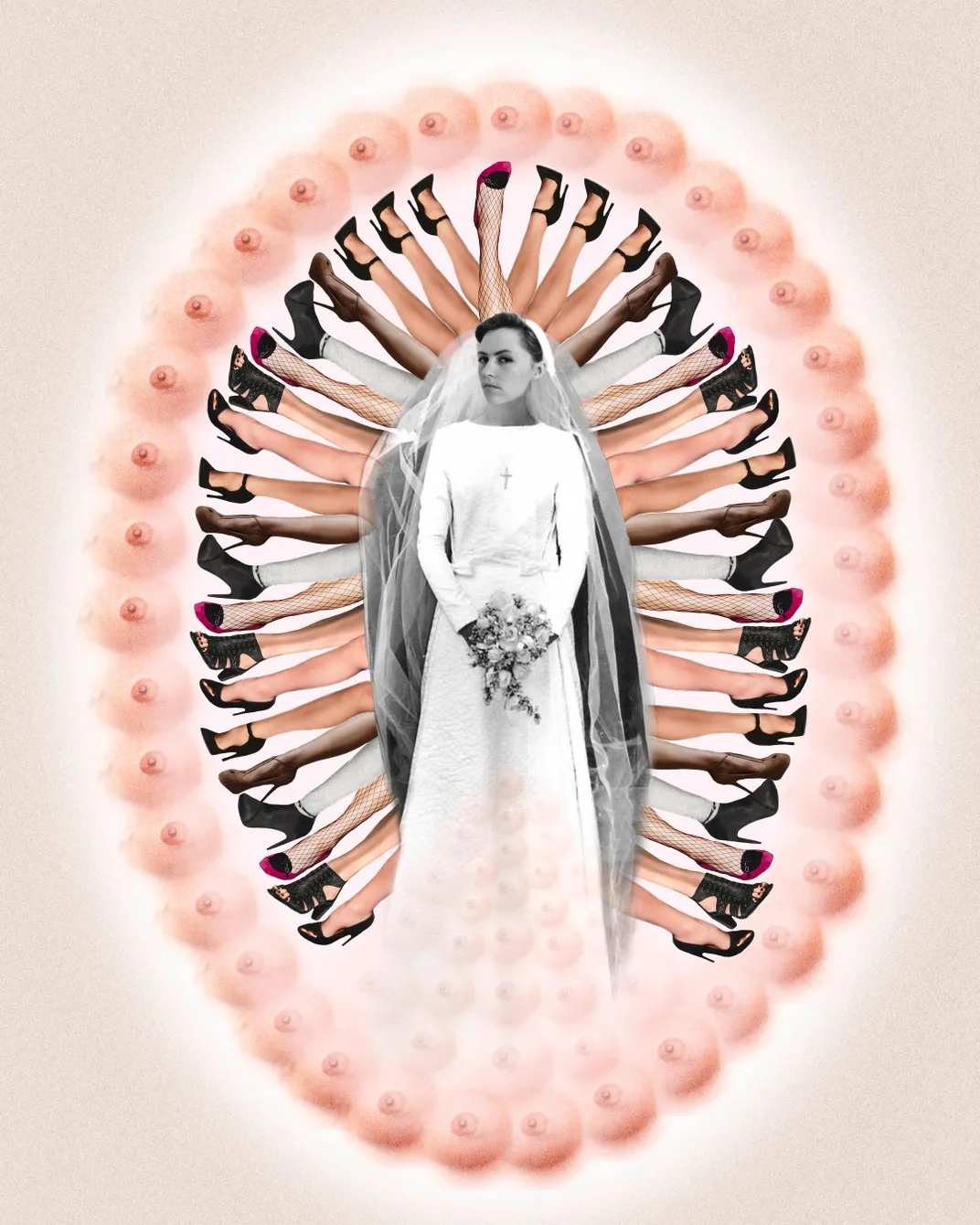

Opening on February 6, 2022, “Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” will encourage debate and disagreement. Per the statement, the exhibition features 68 works by 38 artists, including two new commissions. It is divided into five thematic sections: “La Lengua/The Interpreter,” “La Indígena/The Indigenous Woman,” “La Madre de Mestizaje/The Mother of a Mixed Race,” “La Traidora/The Traitor” and “‘Chicana’/Contemporary Reclamations.”

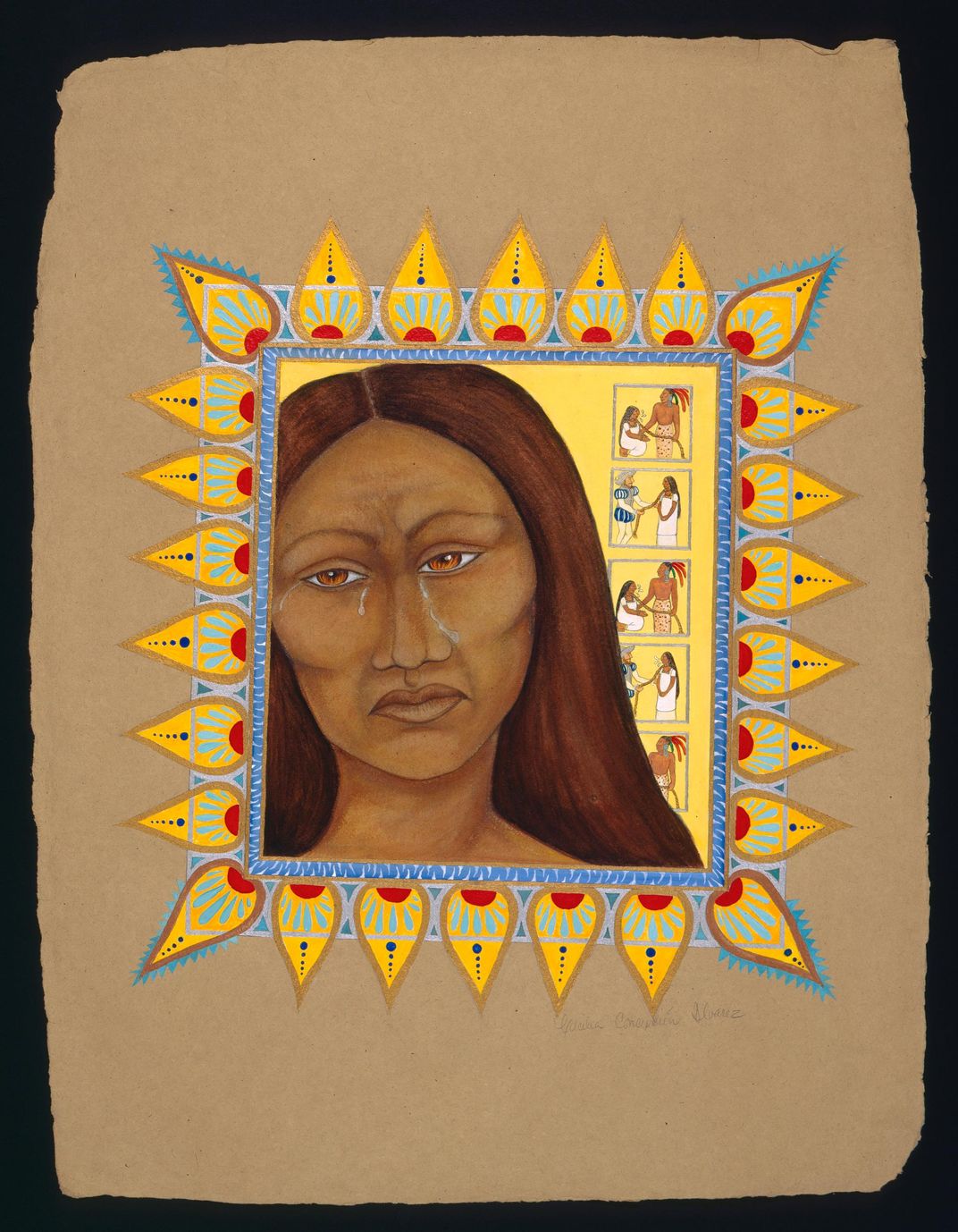

One of the show’s highlights is Cecilia Alvarez’s La Malinche Tenía Sus Razones (1995), which depicts a tearful Malinche in the foreground and a polyptych of her enslavement and trade to Cortés behind her. Translated as Malinche Had Her Reasons, the painting’s title hints at a newfound empathy for this controversial figure.

According to the New-York Historical Society, Malinche was sold or kidnapped into slavery as a young girl. When Cortés conquered the Maya city of Potonchán in 1519, its inhabitants gave him gifts of gold and enslaved women and girls—including Malinche. Though her exact date of birth is unknown (some historical accounts suggest 1500), she was likely in her late teens by this point.

Malinche went by a number of names, including Malinal, Malintzin and Doña Marina. As historian Federico Navarrete tells the Mexico Daily Post, “Like many women who are held captive, most likely the woman we know as Marina or Malintzin lost her original name when she was taken from her family or her original context."

After becoming aware of Malinche’s multilingualism, Cortés exploited her knowledge and kept her by his side. Writing for JSTOR Daily in 2019, Farah Mohammed explained, “Throughout Cortés’s travels, Malintzin became indispensable as a translator, not only capable of functionally translating from one language to the other, but of speaking compellingly, strategizing, and forging political connections.”

In October 1519, Malinche reportedly saved the Spaniards from an impending attack, warning Cortés of an ambush in the Aztec city of Cholula after learning the group’s attack plan from an old woman.

“On [this] and other occasions, La Malinche’s presence made the decisive difference between life or death,” wrote scholar Cordelia Candelaria in the journal Frontiers in 1980.

Cortés retaliated against the planned uprising by massacring thousands of Cholulans. Though many accounts blame Malinche for tipping him off, others suggest that the entire narrative was constructed by conquistador to justify his bloody actions.

Around 1523, Malinche gave birth to Cortés’ first-born son, Martín. In doing so, notes the DAM statement, “she became the symbolic progenitor of a modern Mexican nation, built on both Indigenous and Spanish heritage.” Archival documents indicate that Malinche died in 1527 or 1528, around the age of 25, but offer few insights on her later life.

“We’ve built this whole romantic legend about Cortés and Malintzin but I believe that does nothing more than subordinate her to Cortés and convert him into a typical disagreeable male who leaves her behind and throws her in the trash,” Navarrete tells Mexico News Daily. “[S]he’s turned into a disposable person and that’s not Malintzin at all if we look at her history.”

After Mexico won its independence from Spain in the early 20th century, Malinche was transformed into a symbol, the truth of her experiences muddled by widespread hatred toward the conquistadors. She became a traitor in public memory due to her aiding and abetting of the conquest of Latin America and the genocide of its people—her own people. Mexican slang has even memorialized her name in the term malinchista, which refers to someone who is disloyal to their country or abandons their own culture for another.

But Malinche may also be considered a survivor who worked within the constraints of her enslavement and exhibited as much agency as she could. Icon is a fitting characterization for Malinche, too, as her image has ignited conversation around national identity, colonization and womanhood for centuries.

Malinche’s story bears striking parallels to that of Pocahontas, though the two women’s presentation in the media diverges significantly, with Malinche largely being depicted more negatively.

“She is the Mexican Eve,” Sandra Cypress, author of La Malinche in Mexican Literature: From History to Myth, told Jasmine Garsd of NPR in 2015.

The upcoming exhibition, for its part, “presents Malinche’s generally unfamiliar and complex story to contemporary audiences through the work of artists across centuries and cultures, illuminating themes of identity, womanhood and agency that have sustained relevance across time,” as the DAM’s director, Christoph Heinrich, says in the statement.

One work on display in the show, Antonio Ruíz’s 1939 painting El sueño de la Malinche, depicts a slumbering Malinche in a gilded bedframe, her expression troubled, as Mexican architecture rises from the landscape created by the slopes of her body within the bedsheets. A crack in the wallpaper resembling a fork of lightning reaches out toward her face.

“The enormity and complexity of the story contained in Ruíz’s jewel-like painting is symbolic of the many allegories associated with La Malinche,” notes the statement. “… The glowing beauty of this work with a dark connotation underscores the complex relationship contemporary Mexico still has with Malinche.”

Distilling Malinche’s enduring legacy, co-curator Terezita Romo concludes, “As a figure embraced by Chicana writers and artists, Malinche is the subject of a narrative that [has] been reframed and recently invigorated to reflect a Chicana feminism that resists male-dominated interpretations of her life and significance.”

“Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” will debut at the Denver Art Museum on February 6, 2022.

:focal(305x200:306x201)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/44/bd44682b-84d6-4eea-b4e3-ba1bf7c83c8e/malinche_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/c9/0dc96f4a-c9d7-4197-8566-7124158d55b8/la_malinche_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/graciephoto.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/graciephoto.jpg)