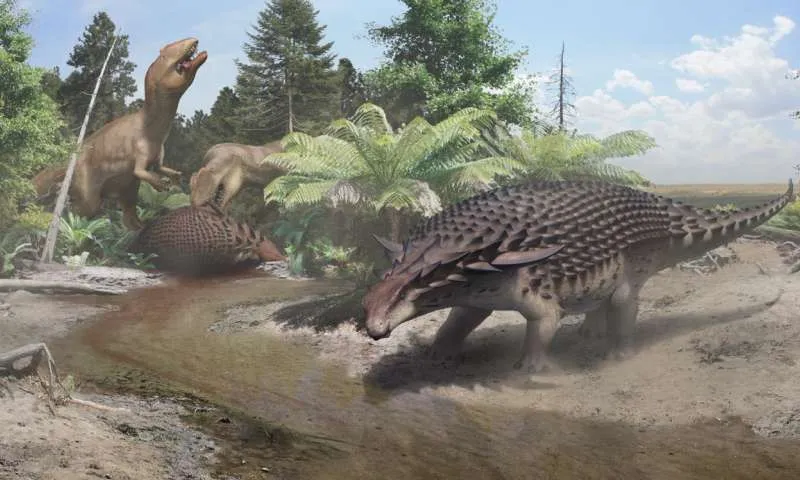

Was the “Sleeping Dragon” Dinosaur a Red Head?

A new study suggests the perfectly preserved armored nodosaur camoflauged itself against marauding meat-eaters

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/a0/43a07a27-a303-4276-8273-f887458c4786/sleeping_dragon.jpg)

In May, the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta debuted a stunning fossil, a life-like “mummy” of a 110-million-year old armored nodosaur that some people dubbed “the sleeping dragon.”

The creature is preserved in stunning detail—from its stomach contents to its plate-like armor. In addition to these features, a thin organic film covered parts of its body, reports Nicola Davis at The Guardian. Now scientists have analyzed that film and made a surprising discovery: The dinosaur likely sported a reddish coloring on top. They published their results in the journal Current Biology.

It’s believed that after the dino died, it fell back-first into the muddy floor of the ocean. That perfectly preserved the top half of the creature. “The result is that the animal looks almost the same today as it did back in the Early Cretaceous. You don't need to use much imagination to reconstruct it; if you just squint your eyes a bit, you could almost believe it was sleeping,” Donald Henderson, Curator of Dinosaurs at the Royal Tyrell Museum says in a press release. “It will go down in science history as one of the most beautiful and best preserved dinosaur specimens—the Mona Lisa of dinosaurs.”

Discovered by accident in 2011, scientists have since been working to analyze the creature, teasing out details about its physical looks and life. As Davis reports, scientists discovered that the black film contained traces of elements that are associated with red pigmentation. "We could see that the organic compounds [in the film] were something that contained carbon, nitrogen and sulfur—that is something that we know is typical for [the pigment] red melanin," University of Bristol molecular paleobiologist Jakob Vinther tells Davis.

The film was only found on the top of the nodosaur, which suggests that it was red on top and pale on its underside—a color pattering known as countershading in which the critter's top and bottom halves are different colors. This flattens the animal's appearance at a distance, making it harder for predators to spot. While modern prey species like deer and chipmunks are countershaded, heavily armored species (such as rhinos) or predators (such as brown bears) don't generally sport this useful camouflage pattern.

As Davis reports, if this tank-like plant-eater—who likely weighed in at nearly 3,000 pounds and measured up to 18 feet long in life—needed counter-shading to hide from hungry carnivores, this conflicts with the common idea that large dinosaurs like T. rex were primarily scavengers.

“That [this nodosaur] is camouflaged means that it still was experiencing predation regularly—these animals got gobbled up and eaten by the large theropod dinosaurs,” Vinther tells Davis. “Things were scary back then.”

Not everyone is convinced that the nodosaur sported this red coloration—or what the coloring could imply about its life history. Alison Moyer who studies fossilized tissue at Drexel University tells Michael Greshko at National Geographic that the organic film found on the sleeping dragon could have come from bacteria that grew on the decaying corpse after death. She also notes that the preserved dinosaur hide doesn’t reach the animal’s belly, meaning the underside could have been the same color.

Even if the creature was two toned, Moyer cautions against drawing too many conclusions based on these looks. “[T]he study relating to the pigmentation and coloration—and, therefore, conclusions about predator-prey relationships—is kind of flooded with issues,” Moyer tells Greshko. “There are endless possibilities that aren’t considered that would be more parsimonious than jumping to this countershading.”

Whatever color the nodosaur was, it’s still extraordinary, and the study serves as the species debut in the scientific literature. According to a press release, the creature now officially represents a new genus and species of dinosaur, Borealopelta markmitchelli, named after Mark Mitchell, the museum technician who spent five and a half years meticulously removing rock from the specimen after it was found in 2011 in Alberta’s Suncor Millennium Mine.

The specimen is currently on display at the Royal Tyrell Museum.