Watch the World’s Oldest Working Computer Turn On

The Harwell Dekatron—also known as the Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computation or the WITCH computer—was built in 1951

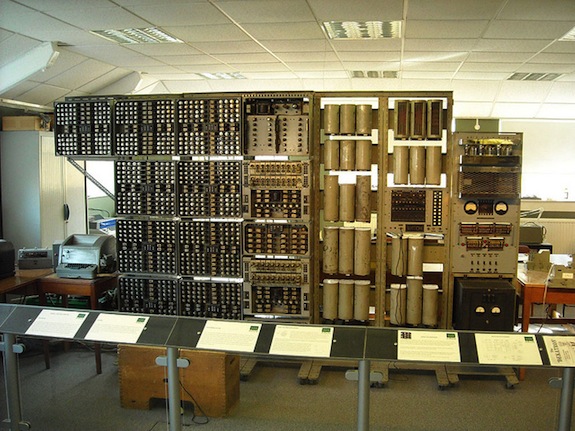

The Dekatron. Image: Nelson Cunningham

This is the Harwell Dekatron, also known as the Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computation or the WITCH computer. It was built in 1951, which makes it the oldest working digital computer in the world. This is what it takes to turn it on.

The Dekatron currently lives at the National Museum of Computer in Buckinghamshire, UK. Open Culture explains the process of restoration:

A three-year restoration of the computer — all two-and-a-half tons, 828 flashing Dekatron valves, and 480 relays of it — began in 2008. Now, having just finished returning the machine to tip-top shape, they’ve actually booted it up, as you can see. “In 1951 the Harwell Dekatron was one of perhaps a dozen computers in the world,” The National Museum of Computing’s press release quotes its trustee Kevin Murrell as saying, “and since then it has led a charmed life surviving intact while its contemporaries were recycled or destroyed.”

According to the NMOC, after the Dekatron completed its first tasks at the Harwell Atomic Energy Research Establishment, it lived on until 1973:

Designed for reliability rather than speed, it could carry on relentlessly for days at a time delivering its error-free results. It wasn’t even binary, but worked in decimal — a feature that is beautifully displayed by its flashing Dekatron valves.

By 1957, the computer had become redundant at Harwell, but an imaginative scientist at the atomic establishment arranged a competition to offer it to the educational establishment putting up the best case for its continued use. Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College won, renamed it the WITCH (Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computation from Harwell) and used it in computer education until 1973.

They also list the technical specifications of the computer:

Power Consumption: 1.5kW

Size 2m high x 6m wide x 1m deep

Weight: 2.5 tonnes

Number of Dekatron counter tubes: 828

Number of other valves: 131

Number of relays: 480

Number of contacts or relay switches: 7073

Number of high speed relays: 26

Number of lamps: 199

Number of switches: 18

More from Smithsonian.com:

Charles Babbage’s Difference Machine No. 2

Can Computers Decipher a 5,000-Year-Old Language?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)