What Happened When Woodrow Wilson Came Down With the 1918 Flu?

The president contracted influenza while attending peace talks in Paris, but the nation was never told the full, true story

:focal(1735x426:1736x427)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/77/1677f9ef-91e4-4c0e-bca9-4486dbabffd0/gettyimages-3396975.jpg)

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed an estimated 50 to 100 million people worldwide—including some 675,000 Americans—in just 15 months. But Woodrow Wilson’s White House largely ignored the global health crisis, focusing instead on the Great War enveloping Europe and offering “no leadership or guidance of any kind,” as historian John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, recently told Time’s Melissa August.

“Wilson wanted the focus to remain on the war effort,” Barry explained. “Anything negative was viewed as hurting morale.”

In private, the president acknowledged the threat posed by the virus, which struck a number of people in his inner circle, including his personal secretary, his oldest daughter and multiple Secret Service members. Even the White House sheep came down with the flu, reports Michael S. Rosenwald for the Washington Post.

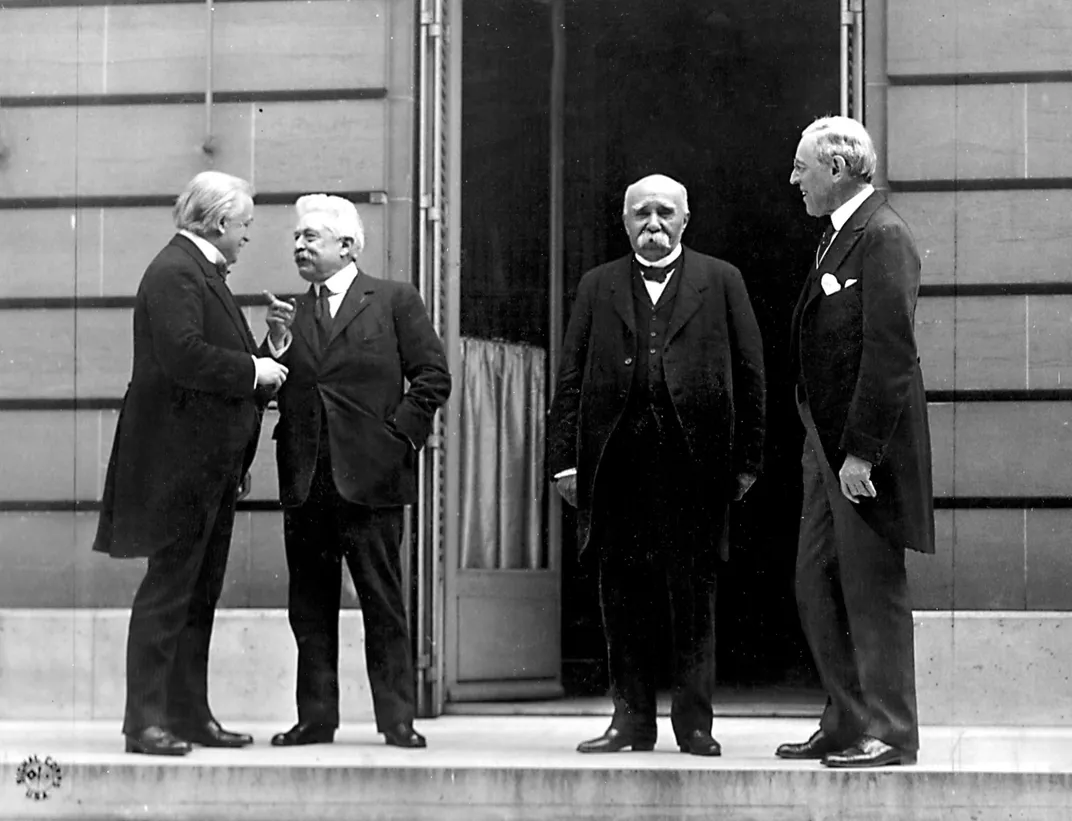

Wilson himself contracted the disease shortly after arriving in Paris in April 1919 for peace talks aimed at determining the direction of a post-World War I Europe. As White House doctor Cary T. Grayson wrote in a letter to a friend, the diagnosis arrived at a decidedly inopportune moment: “The president was suddenly taken violently sick with the influenza at a time when the whole of civilization seemed to be in the balance.”

Grayson and the rest of Wilson’s staff downplayed the president’s illness, telling reporters that overwork and Paris’ “chilly and rainy weather” had sparked a cold and fever. On April 5, the Associated Press reported that Wilson was “not stricken with influenza.”

Behind the scenes, the president was suffering the full force of the virus’ effects. Unable to sit up in bed, he experienced coughing fits, gastrointestinal symptoms and a 103-degree fever.

Then, says biographer A. Scott Berg, the “generally predictable” Wilson started blurting out “unexpected orders”—on two separate occasions, he “created a scene over pieces of furniture that had suddenly disappeared,” despite the fact that nothing had been moved—and exhibiting other signs of severe disorientation. At one point, the president became convinced that he was surrounded by French spies.

“[W]e could but surmise that something queer was happening in his mind,” Chief Usher Irwin Hoover later recalled. “One thing was certain: [H]e was never the same after this little spell of sickness.”

Wilson’s bout of influenza “weaken[ed] him physically … at the most crucial point of negotiations,” writes Barry in The Great Influenza. As Steve Coll explained for the New Yorker earlier this year, the president had originally argued that the Allies “should go easy” on Germany to facilitate the success of his pet project, the League of Nations. But French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, whose country had endured much devastation during the four-year conflict, wanted to take a tougher stance; days after coming down with the flu, an exhausted Wilson conceded to the other world leaders’ demands, setting the stage for what Coll describes as “a settlement so harsh and onerous to Germans that it became a provocative cause of revived German nationalism … and, eventually, a rallying cause of Adolf Hitler.”

Whether Wilson would have pushed harder for more equitable terms if he hadn’t come down with the flu is, of course, impossible to discern. According to Barry, the illness certainly drained his stamina and impeded his concentration, in addition to affecting “his mind in other, deeper ways.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/a2/0da25d89-88da-43de-a0eb-15d787c132f6/screen_shot_2020-10-02_at_123427_pm.png)

Despite his personal experience with the pandemic, the president never publicly acknowledged the disease wreaking havoc on the world. And though Wilson recovered from the virus, contemporaries and historians alike argue that he was never quite the same.

Six months after he came down with the flu, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke that left him paralyzed on his left side and partially blind. Instead of disclosing her husband’s stroke, First Lady Edith Wilson hid his life-threatening condition from politicians, the press and the public, embarking on a self-described “stewardship” that Howard Markel of “PBS Newshour” more accurately defines as a secret presidency.

The first lady was able to assume such broad power due to a lack of constitutional clarity regarding the circumstances under which a president is considered incapacitated. A clearer protocol was only established with the ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967.

As Manuel Roig-Franzia wrote for the Washington Post in 2016, Edith’s “control of the flow of information did not go unnoticed by an increasingly skeptical Congress.” At one point, Senator Albert Fall even declared, “We have a petticoat government! Wilson is not acting! Mrs. Wilson is President!”

Though Wilson’s condition improved marginally in the final years of his presidency, Edith continued, for all intents and purposes, to serve as the nation’s chief executive until her husband left office in March 1921. The weakened president died three years later, on February 3, 1924.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)