The Little-Known Story of World War II’s ‘Last Million’ Displaced People

A new book by historian David Nasaw tells the story of refugees who could not—or would not—return home after the conflict

:focal(2102x960:2103x961)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/72/f5727c8d-0d68-4fcc-9264-482702ea8705/gettyimages-517393500.jpg)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, upward of six million concentration camp survivors, prisoners of war, enslaved laborers, Nazi collaborators and political prisoners flocked to Germany. The Allies repatriated the majority of these individuals to their home countries (or helped them resettle elsewhere) within the next several months. But by late 1945, more than one million remained unable—or unwilling—to return home.

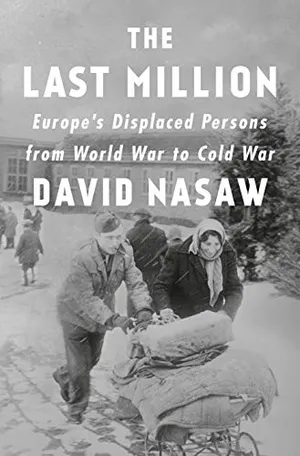

A new book by historian David Nasaw chronicles these displaced persons’ stories, exploring the political factors that prevented them from finding asylum. Titled The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons From World War to Cold War, the text follows the “three to five years [refugees spent] in displaced persons camps, temporary homelands in exile, divided by nationality, with their own police forces, churches and synagogues, schools, newspapers, theaters, and infirmaries,” per the book’s description.

The Allied troops who occupied Germany at the end of the war were “astounded” and “horrified” by what they saw, Nasaw tells Dave Davies of NPR.

“They had expected to see a Germany that looked much like London had after the Blitz, where there was extensive damage,” he says. “But the damage was a thousand times worse, and the number of homeless, shelterless, starving humans was overwhelming.”

The Last Million: Europe's Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War

From bestselling author David Nasaw, a sweeping new history of the one million refugees left behind in Germany after WWII

As Nasaw explains, most displaced people came to Germany as laborers, former Nazi collaborators or concentration camp survivors.

The first of these groups arrived during the war, when millions of Eastern Europeans traveled to Germany as enslaved, forced or guest laborers. Deemed “subhuman workers” by Adolf Hitler, they toiled away in factories and fields to help sustain the Nazi war effort.

Later, when the Third Reich fell in May 1945, many Baltic citizens who had collaborated with the Nazis retreated to Germany in hopes of escaping the approaching Red Army. Some of these displaced people feared prosecution if they returned to a Soviet-controlled state, writes Glenn C. Altschuler for the Jerusalem Post.

Jews and other imprisoned in concentration camps across the Third Reich, meanwhile, were sent on death marches to Germany toward the end of the war.

“The goal was not to bring them to safety in Germany but to work them to death in underground factories in Germany, rather than gas them in Poland,” Nasaw tells NPR.

By the war’s conclusion, the Soviet Union controlled much of Eastern Europe. Fearful of becoming Soviet slaves, as suggested by Nazi propaganda, or returning to a country rampant with anti-Semitism, many Jews opted to remain in Germany, where they believed Allied forces might offer them resettlement.

The ongoing crisis spurred the establishment of the International Refugee Organization in April 1946. But while the United Nations group successfully repatriated many non-Jewish refugees, roughly a quarter million displaced Jews remained trapped in Germany, per the book’s description.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/d7/90d7bc88-2458-4ff6-a5a3-fccb148a9027/postwwiiberlindpcampfootballteamusofficersanddpcampadminstrationinbackrow_schwartzbergissecondfromright.jpg)

In 1948, the United States passed the Displaced Persons Act. Though the legislation was designed to resettle thousands of European refugees, it only granted visas to those who had entered refugee camps before December 1945. Because of this stipulation, Jews who had survived the Holocaust and returned home to Poland, only to face pogroms and subsequently flee to Germany, were excluded.

By the end of the decade, fears regarding Communism and the Cold War had surmounted memories of the terrors of the Holocaust, argues Nasaw in The Last Million. Only those who were “reliably anti-Communist” received entry visas. This policy excluded many Jews who were recent residents of Soviet-dominated Poland—but allowed “untold numbers of anti-Semites, Nazi collaborators and war criminals” to enter the U.S., according to the historian.

President Harry Truman, who signed the act, recognized its xenophobic and anti-Semitic biases.

“The bad points of the bill are numerous,” he said in a 1948 speech quoted by the Truman Library Institute. “Together they form a pattern of discrimination and intolerance wholly inconsistent with the American sense of justice.”

Based on Nasaw’s research, only about 50,000 of the quarter million Jews seeking resettlement were admitted to the U.S. under the Displaced Persons Act. (“Significant numbers” also settled in Canada, he says.) Those from Latvia, Estonia, Poland and Yugoslavia were resettled elsewhere.

As the Jerusalem Post notes, displaced Jews hoping to move to Palestine were blocked from doing so until the establishment of the independent state of Israel in 1948. Ultimately, Nasaw tells NPR, around 150,000 Jewish refugees settled in Israel.

The last displaced persons to leave Germany only did so in 1957—a full 12 years after the war ended.

Overall, Publishers Weekly concludes in its review, Nasaw argues that “a humanitarian approach to the crisis often yielded to narrow, long-term foreign policy goals and Cold War considerations.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)