What the First Three Patents Say About Early America

Gunpowder, fertilizer, soap, candles and flour were all important to Americans

:focal(461x205:462x206)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/03/0a0381da-ce0a-4f1c-a3ce-67cbba7b3fcd/candle.jpg)

The first State of the Union, the first census and the first patent: 1790 was a big year.

On July 31, 1790–just a few months after creating a government structure to handle patents–the government of the Unites States issued its first patent. It was one of only three that would be issued that year, according to Lucas Reilly for Mental Floss. Those first three patents offer a fascinating glimpse into what the inventors of a new nation thought was worth improving on. Take a look:

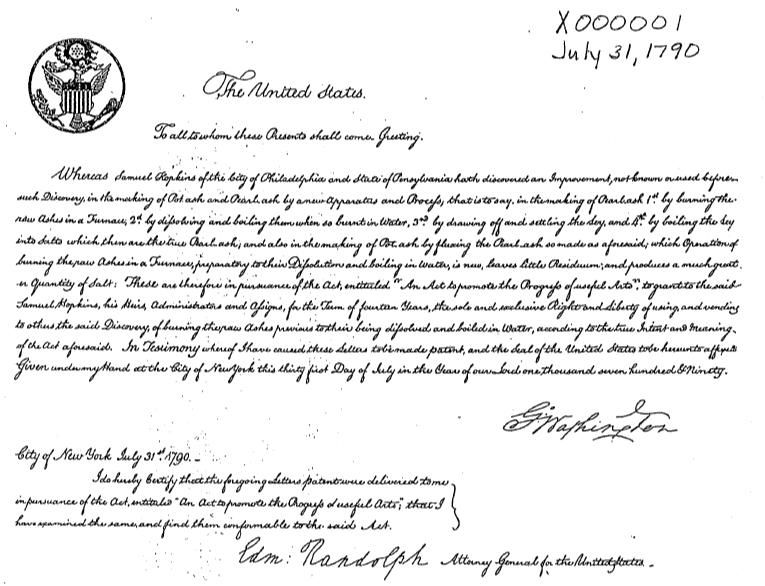

Potash and Pearl Ash

The first patent bears a United States seal and the signature of President George Washington himself, but it differs from modern patents in other ways–like beginning with a salutation. “Too all to whom these Presents shall come, Greeting,” it begins.

Beyond that, the patent describes a new process for making potash and pearl ash patented by Samuel Hopkins of Philadelphia. “Potash and pearl ash were important ingredients in making glass, china, soap and fertilizer,” writes Randy Alfred for Wired.

Potash was also an important ingredient in saltpeter, which was in turn an ingredient in gunpowder–an important substance during the revolutionary years. Pearl ash, a more refined version of potash, was briefly also used a pre-baking soda food leavener, writes food history blogger Sarah Lohman. They were made by burning hardwood trees and soaking the ashes. Hopkins’s new process, which involved burning the ashes a second time in a furnace, allowed more potash to be extracted.

Both were important to fledgling America, writes Henry M. Paynter for the University of Texas. There was great demand for the products, and plenty of wood ashes were at hand as settlers cleared land, often by burning great numbers of trees. “These pioneers soon realized that the heaps of woods ashes they were producing could be converted into ‘black gold’ worth hard cash.”

Candle manufacturing

There’s only scant evidence about most of the patents from this period. As Reilly records, an 1836 fire where the patents were being stored destroyed most of them. They’re referred to as the X-patents and little is known about most of them (although X0000001, the potash patent, is in the collection of the Chicago Historical Society).

The second X-patent was held by a Boston candle maker name Joseph Samuelson, related to–shockingly–the “manufacturing of candles.” At a later date, Reilly writes, he “helped invent the continuous wick.”

Candles were an essential technology in early America, but they were expensive. Most homes in colonial Virginia “included only two candlesticks,” write historians Harold Gill and Lou Powers. Even into the years surrounding the Revolution, candles were a primary form of light, and they were thus a steady cost–so much so that in 1784 Benjamin Franklin wrote a satirical letter proposing something similar to Daylight Savings Time “to lessen, if possible, the expense of lighting our apartments.”

Automated Flour Mill

Oliver Evans’s automated flour mill was claimed to work “without the aid of manual labor, excepting to set the different machines in motion,” according to Reilly. “In his mill near Philadelphia, Evans invented a series of machines that weighed, cleaned and ground the wheat” before packing the flour in barrels, writes historian Norman K. Risjord. “Largely because of Evans’s innovations, American flour mills led the world in efficiency and productivity by 1800,” he writes.

Not bad for the first year.