Smithsonian Curator Reflects on Joe Biden’s ‘Poignant’ Inaugural Painting

Eleanor Harvey posits that the 1859 landscape’s message of hope resonated with First Lady Jill Biden, who helped select the artwork

:focal(1657x828:1658x829)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/7d/6e7d2dda-f65b-4be2-ba22-b8b75ae3794b/saam-198395160_1_1.jpg)

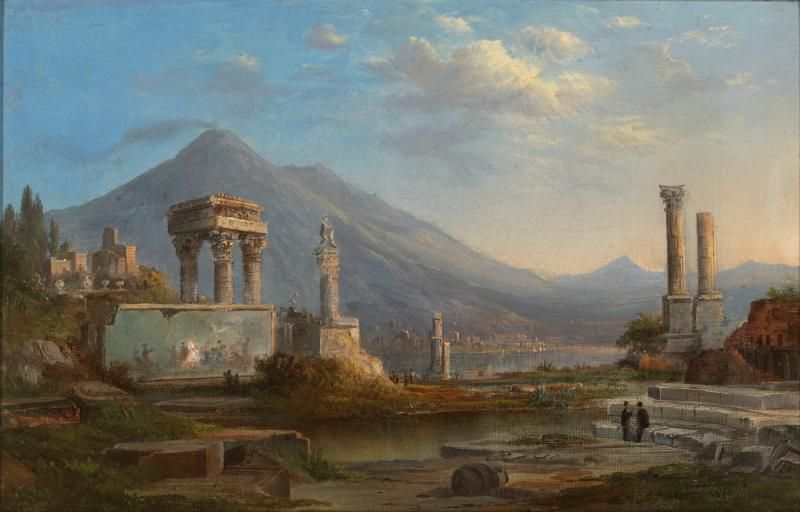

On Wednesday, Republican Senator Roy Blunt presented the newly inaugurated president of the United States, Joe Biden, with a painting on loan from the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) especially for the occasion: Robert S. Duncanson’s Landscape With Rainbow, an 1859 landscape of green fields dotted with cows. In the work, a tiny couple strolls across a lush countryside as cattle graze serenely under a lilac sky. A rainbow shimmers overhead.

In a normal year, this “inaugural painting” would have served as the backdrop for the Senate Inaugural Luncheon and a symbol of the incoming administration’s agenda. But the 59th inaugural ceremonies were anything but normal: The traditional meal was canceled, attendance was limited and all parties donned face masks to prevent the spread of Covid-19. The president and First Lady Jill Biden received the painting in the Capitol Rotunda—the same room overtaken by an angry mob just two weeks earlier.

The first lady helped select Landscape, which was returned to SAAM following the event. As senior curator Eleanor Jones Harvey says in an email, SAAM is among the institutions typically asked to propose artworks for the event. (Per the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott, the tradition is a relatively recent one, only dating back to Ronald Reagan’s second inauguration in 1985.) When the museum’s staff started preparing a list of options, Duncanson’s work “immediately rose to the top of our list,” the curator adds.

Born in 1821, Duncanson was a painter of mixed-race descent who became one of the most successful African American artists of his generation. Though his 1859 scene appears to capture a peaceful moment, some elements hint at “an America on the brink of catastrophe,” as art critic Christopher Knight notes for the Los Angeles Times. In the golden light of the setting sun, nighttime approaches, prompting the cows to move toward the safety of a farmhouse just visible in the background.

As Duncanson painted Landscape, trouble loomed on the horizon. In 1863, four years after the work’s creation, the artist and his family fled from Cincinnati to Canada, where they hoped to escape the ongoing Civil War and mounting anti-black racism. Still, despite sensing the challenges ahead, Duncanson chose to imbue the scene with a sense of optimism.

“[The composition] carries with it an unmistakable ray of hope,” writes the Los Angeles Times. “Rainbows typically appear after a storm has passed, not before.”

Harvey describes the painting as “a poignant reminder that on the brink of dissolution, [Duncanson] held out hope for the future.”

She adds, “I believe that message, and the messenger, appealed to Dr. Biden.”

According to a digital exhibition from the Cincinnati Art Museum, Duncanson’s grandfather was a formerly enslaved Virginian. His parents moved from Virginia to New York, where their son was born. The young artist grew up working for his family’s business as a house painter and glazier.

Eager to prove himself in the fine arts, 19-year-old Duncanson moved to Cincinnati, a prosperous city that was quickly becoming a hub for abolitionists, in 1840. Here, his light-colored skin allowed him to walk “a fine line, acknowledging his heritage without flaunting it,” according to a SAAM blog post by Harvey.

Many of the people who commissioned the young painter’s work were abolitionists. Among these patrons was Nicholas Longworth, a wealthy philanthropist who employed Duncanson to cover the walls of his home with sweeping vistas in the style of the Hudson River School and traditional European landscape painting. These murals, completed between 1850 and 1852 and now part of the Taft Museum of Art’s collection, represent one of the “most significant pre–Civil War domestic murals in the United States,” per the Cincinnati museum’s website.

Duncanson’s paintings soon earned him an international reputation. Funded by an abolitionist group from Ohio, he embarked on a grand tour of Europe in 1853, visiting London, Paris and Florence to study the work of his artistic predecessors.

“I really believe Duncanson wanted to align his paintings with the recognized masters in the United States and Europe,” art historian Claire Perry told Smithsonian magazine’s Lucinda Moore in 2011.

According to Smithsonian, the ambitious painter’s letters from his travels overseas “reveal an understated confidence.”

“My trip to Europe has to some extent enabled me to judge of my own talent,” Duncanson wrote. “Of all the Landscapes I saw in Europe, (and I saw thousands) I do not feel discouraged … Someday I will return.”

The 59th Inaugural Painting, "Landscape with Rainbow" by Robert S. Duncanson, is revealed. pic.twitter.com/1w5E9mbvGF

— #Inaugural59 (@JCCIC) January 20, 2021

Though Duncanson focused on themes of nature in his paintings, he did not eschew politics entirely: In Cincinnati From Covington, Kentucky (circa 1851), for instance, Duncanson depicts enslaved black people laboring in the fields of rural Kentucky in stark contrast with scenes of prosperity and equality seen across the river in Ohio, per the Cincinnati Art Museum.

In 1854, Duncanson collaborated with prominent African American photographer James Presley Ball to create an anti-slavery panorama. Titled the Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade, the 600-yard-wide panorama toured the country, using light and sound effects to display the horrors of human bondage and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Duncanson exhibited Landscape With Rainbow in America to great public acclaim. One contemporary reviewer praised the work as “one of the most beautiful pictures painted on this side of the [Allegheny] mountains,” per SAAM.

When he returned to Europe in the latter half of his life, Duncanson brought his best-known work, Land of the Lotus-Eaters (1861), to the Isle of Wight, where he showed it poet Alfred Tennyson. Tennyson, whose poem “The Lotos-eaters” had inspired the painting, was “delighted,” according to Smithsonian.

At the height of his fame in the 1860s, Duncanson’s health began to rapidly deteriorate. The artist battled fits of seizures and schizophrenia—likely the result of poisoning from a lifetime of working with lead paints, per the Cincinnati Art Museum.

In 1867, the artist returned to the U.S., where he settled down in Detroit. He spent his final months in a sanatorium, dying of unknown causes in December 1872.

As Ryan Patrick Hooper reported for the Detroit Free Press in 2018, Duncanson's grave in the historic Woodland Cemetery in Monroe, Michigan, remained unmarked until local residents campaigned to create a monument in his honor. The tombstone was unveiled in June 2019.

“As a free man of color, living in Cincinnati—an abolitionist stronghold—Duncanson was able to be a successful artist,” Harvey says. “His choice to focus on landscape painting reflects the power of that genre to convey our cultural aspirations, and this composition fulfills that yearning for peace and prosperity—the benefits of democracy—for all, regardless of race.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/d5/e3d580fc-588e-4323-83a2-173e06c7e2f4/i-119781.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/65/92658484-a8f7-49fd-88f4-345f43bbd7b8/land_of_lotus_eaters.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)