The British Library’s Dirtiest Books Have Been Digitized

The collection includes around 2,500 volumes and many, many double entendres

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/52/0552c252-91d6-40c5-95a6-593ae96a28f5/istock-665878098.jpg)

For more than 100 years, the British Library kept thousands of its dirtiest books locked away from the rest of its collections. All volumes deemed to be in need of extra safeguarding so that members of the public couldn’t freely get their hands on the saucy stories—or try to destroy them—were placed in the library’s “Private Case.”

But times have changed. According to Alison Flood of the Guardian, the “Private Case” has gotten more public facing through a recent digitization effort that’s part of publisher Gale’s Archives of Sexuality & Gender series.

Previous installments of the project had focused specifically on LGBTQ history and culture, but the third and most recent effort includes a broad range of literature dating from the 16th to 20th centuries. In addition to the British Library, the Kinsey Institute and the New York Academy of Medicine contributed materials to the project. In total, Gale said in a statement, it has digitized 1 million pages of content that were traditionally only available through restricted access in reading rooms.

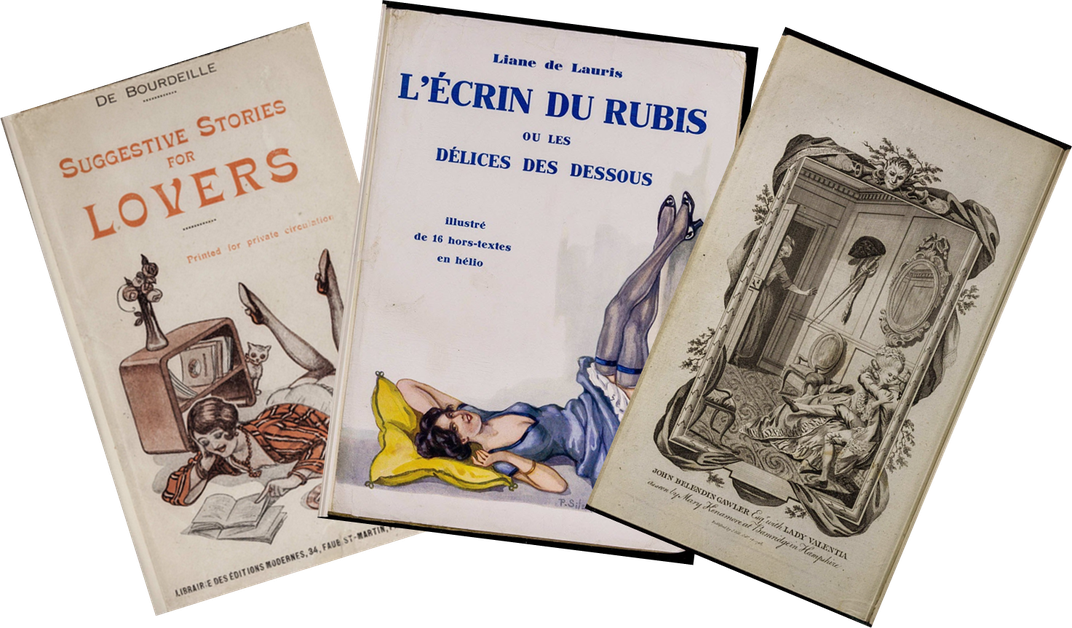

The British Library collection includes around 2,500 volumes and many, many double entendres. Take, for instance, Fanny Hill (also known as Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure) by the 18th-century British writer John Cleland, which is believed to be the first pornographic novel ever written in English. It would not be the last.

Some of the books once sequestered in the “Private Case” wouldn’t be viewed as obscene today, like Teleny, a novel about a homosexual love affair that some believe was penned by Oscar Wilde. But some works still come across as rather … filthy. The collection includes, for instance, the writing of Marquis de Sade, an 18th-century French nobleman who penned what is arguably the most depraved text in the history of literature. Less troubling, but still quite salacious, are the Merryland Books, a series of texts by various authors who used ridiculous pseudonyms like Roger (ahem) Pheuquewell. The books are silly and euphemistic, describing the female body and sexual acts using various topographical metaphors (think large “instruments” ploughing fields).

Women, of course, feature prominently in these texts, but Maddy Smith, curator of printed collections at the British Library, tells Flood that “[a]ll of these works are pretty much written by men, for men.”

“It’s to be expected,” Smith adds, “but looking back, that’s what is shocking, how male-dominated it is, the lack of female agency.”

Opening the collection up to the public has been an ongoing process. In past decades, the library occasionally moved a number of books out of seclusion as sexual mores shifted. In the 1960s, rules about who could access the Private Case were loosened, and in the 1970s, librarians finally got to work cataloguing the collection. The digitized volumes can now be viewed through subscriptions to libraries and educational institutions, or for free at the British Library’s reading rooms in London and Yorkshire. In other words, it is easier than ever before to explore the collection and get a sense of the ways in which our thinking about sex and sexuality has changed over the centuries—and the ways in which it hasn’t.