Who Was Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, the New Namesake of Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive?

Chicago leaders voted to rename the city’s iconic lakeside roadway after a Black trader and the first non-Indigenous settler in the region

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/4d/714deacd-7baa-47f2-a671-cd58a3c44718/chicago-_lake_shore_drive_9694638828.jpeg)

One of Chicago’s most iconic and scenic thoroughfares has a new name, report John Byrne and Gregory Pratt for the Chicago Tribune. Last week, the City Council voted to rename Lake Shore Drive to Jean Baptiste Point DuSable Lake Shore Drive, in honor of the Black trader cited as the first non-Indigenous settler of the Midwestern city.

The change will impact 17 miles of the outer Lake Shore Drive, the ribbon of road that winds around the city and separates residential areas on the west from a bike path, parks and Lake Michigan on the east. Alderman David Moore and the group Black Heroes Matter first proposed renaming Lake Shore Drive after DuSable in 2019.

Leaders voted 33 to 15 in favor of the change, after weeks of debate and tense meetings, reports Becky Vevea for WBEZ Chicago. Mayor Lori Lightfoot initially opposed the name change as she argued it would create chaos at the post office, with many buildings needing to change their addresses. Other opponents to the renaming plan cited the projected cost of sign changes and the road’s long history.

Speaking on Friday in support of the name change, Alderman Sophia King acknowledged the controversy.

“It’s been argued not to change Lake Shore Drive because it’s so iconic,” King said, as Justin Laurence reports for Block Club Chicago. “I argue just the opposite, let’s change it because it’s so iconic. … I hope our story is that we choose a name that is about racial healing and reckoning to honor our founder, who happens to be Black and Haitian.”

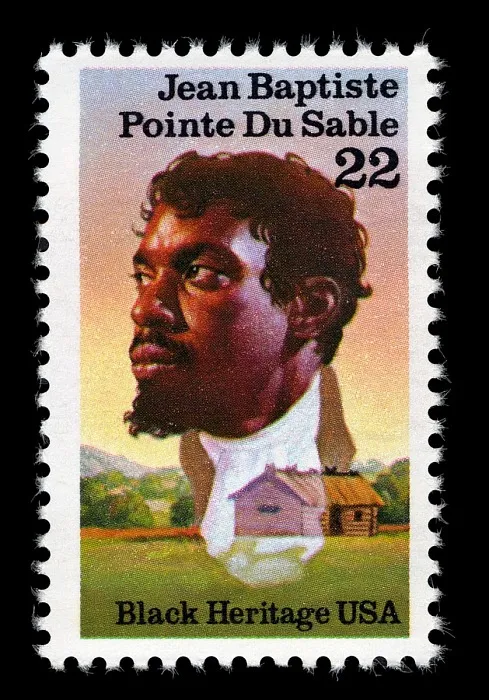

Although evidence about his early life remains scant, DuSable was likely born on the island of Haiti sometime around 1745 to a French father and a Black enslaved mother, as WTTW reported in a 2010 feature on Chicago’s Black history. He was educated in France and then sailed to New Orleans, making his way up the Mississippi River to Illinois.

With his wife, an Indigenous woman named Kitihawa who was likely Potawatomi, DuSable established a cabin on the Chicago River’s northern bank around 1779, becoming the first non-Indigenous person to settle in the region. The couple eventually established a farm and trading post, which succeeded in large part thanks to the translation aid of Kitihawa, as Jesse Dukes reported for WBEZ’s Curious City in 2017. Kitihawa acted as a liaison, enabling DuSable to sell wares such as fur and alcohol to nearby Native American villages and European explorers that passed through on the portage from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi river.

As Rick Kogan explained for the Chicago Tribune in 2019, many historians and Indigenous leaders in Chicago contend that describing DuSable as a “founder” erases the crucial role that Indigenous people played in shaping the city. Thousands of Algonquian language-speaking Native American families had settled in villages throughout the region by the early 19th century, according to Curious City.

European planners used the contours of major Native American trails to determine Chicago’s major streets. And an Anishinaabe word for “skunk” might have inspired the city’s name, as Alex Schwartz reported for Atlas Obscura in 2019.

In an op-ed for the Chicago Sun-Times about the impending name change, Loyola University historian Theodore J. Karamanski argued that emphasis on DuSable’s role as “founder” runs the risk of “myth-making,” and overlooks the trader’s complicity in European settler colonialism and the violent ethnic cleansing of Native Americans from the region. Most, but not all, Indigenous tribes were forced to leave the region in 1833 after they were coerced into signing the Treaty of Chicago, which forfeited 15 million acres of land to the U.S. government, per Atlas Obscura.

Fur traders like DuSable “were the advance guard of the international capitalist market and invasive settlement,” the historian notes.

DuSable, Kitihawa and their two children only resided by the Chicago River for about a year. In 1800, the family sold their property and traveled west to St. Charles, Missouri, where DuSable died in 1818, per WTTW.

“In the wake of DuSable’s pioneering Chicago River settlement, the U.S. Army erected Fort Dearborn, an event memorialized today by a star on Chicago’s flag,” Karamanski writes. “But Chicago area Indians saw the building of the fort for what it was, the military occupation of their homeland.”

Chicago has renamed major streets before: In 1968, then-Mayor Richard J. Daley renamed South Park Way to Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, shortly after the civil rights leader was assassinated. And in 2018, the city renamed the downtown Congress Parkway to Ida B. Wells Drive, after the groundbreaking journalist and anti-lynching activist.

According to the Chicago Public Library, Lake Shore Drive as it stands today owes its beginnings to an 1869 act that established the Lincoln Park District on Chicago’s north side. The thoroughfare will join a host of other Chicago fixtures to bear DuSable’s name, including a public high school, bridge, harbor and the DuSable Museum of African American History, a Smithsonian affiliate museum.

In other Chicago landmark news, a monument dedicated to journalist Wells is set to be dedicated Wednesday in the historic Bronzeville neighborhood. The sculpture by Richard Hunt, entitled Light of Truth, will be the first monument dedicated to a Black woman in the city, as Jamie Nesbitt Golden reports for Block Club Chicago.

Editor's note, April 4, 2022: This story has been edited to reflect that it was Mayor Richard J. Daley, not his son, Richard M. Daley, who renamed South Park Way after Martin Luther King, Jr.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)