Who Scribbled This Cryptic Graffiti on ‘The Scream’?

New research suggests that the painting’s artist, Edvard Munch, wrote the secret message around 1895

:focal(1600x1016:1601x1017)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/c9/3ac9109d-3c41-4ea0-9ec4-e83d984f9dd5/ir_photography_at_the_national_museum_2_photo_annar_bjorgli_the_national_museum_1.jpg)

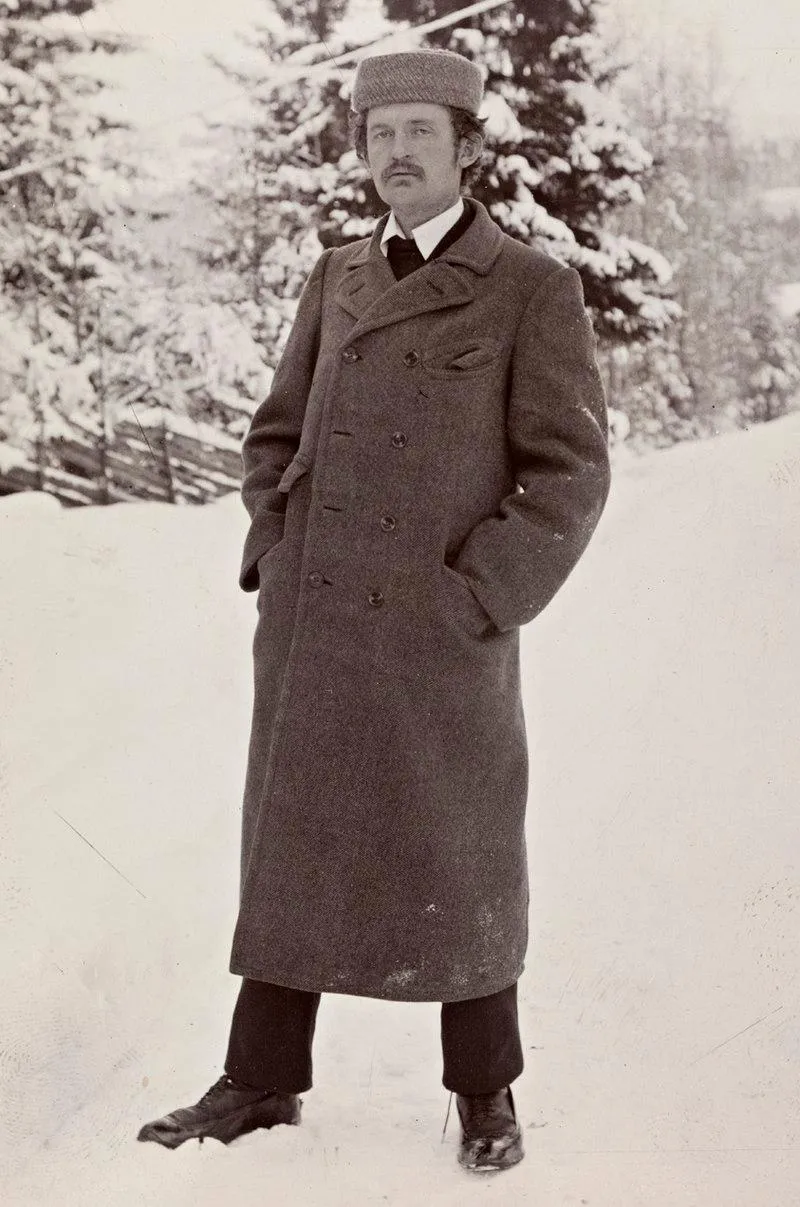

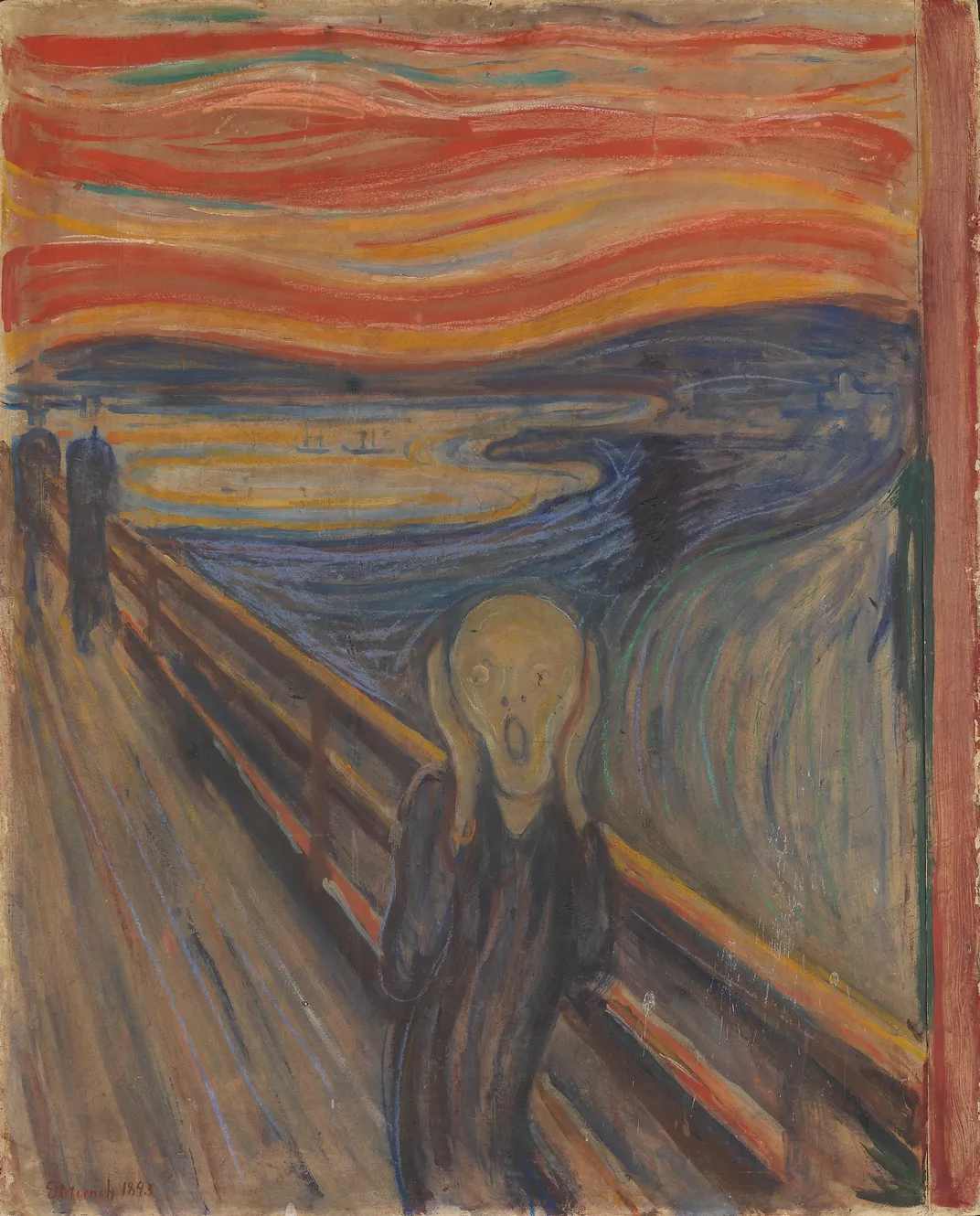

Edvard Munch’s The Scream attracted intense criticism when it was first exhibited in Norway in 1895. Some viewers interpreted the open-mouthed central figure, who stands on a bridge in a sea of swirling color, as an embodiment of the artist’s own fragile mental health.

Historians have long speculated that this controversy provoked a viewer to pencil a curious piece of graffiti on the top left corner of the canvas. The Norwegian message translates to “Could only have been painted by a madman!”

The scribbler who penned the cryptic note remained anonymous—until now. As the National Museum of Norway announced this week, new research suggests the writer wasn’t a disgruntled critic, but Munch himself.

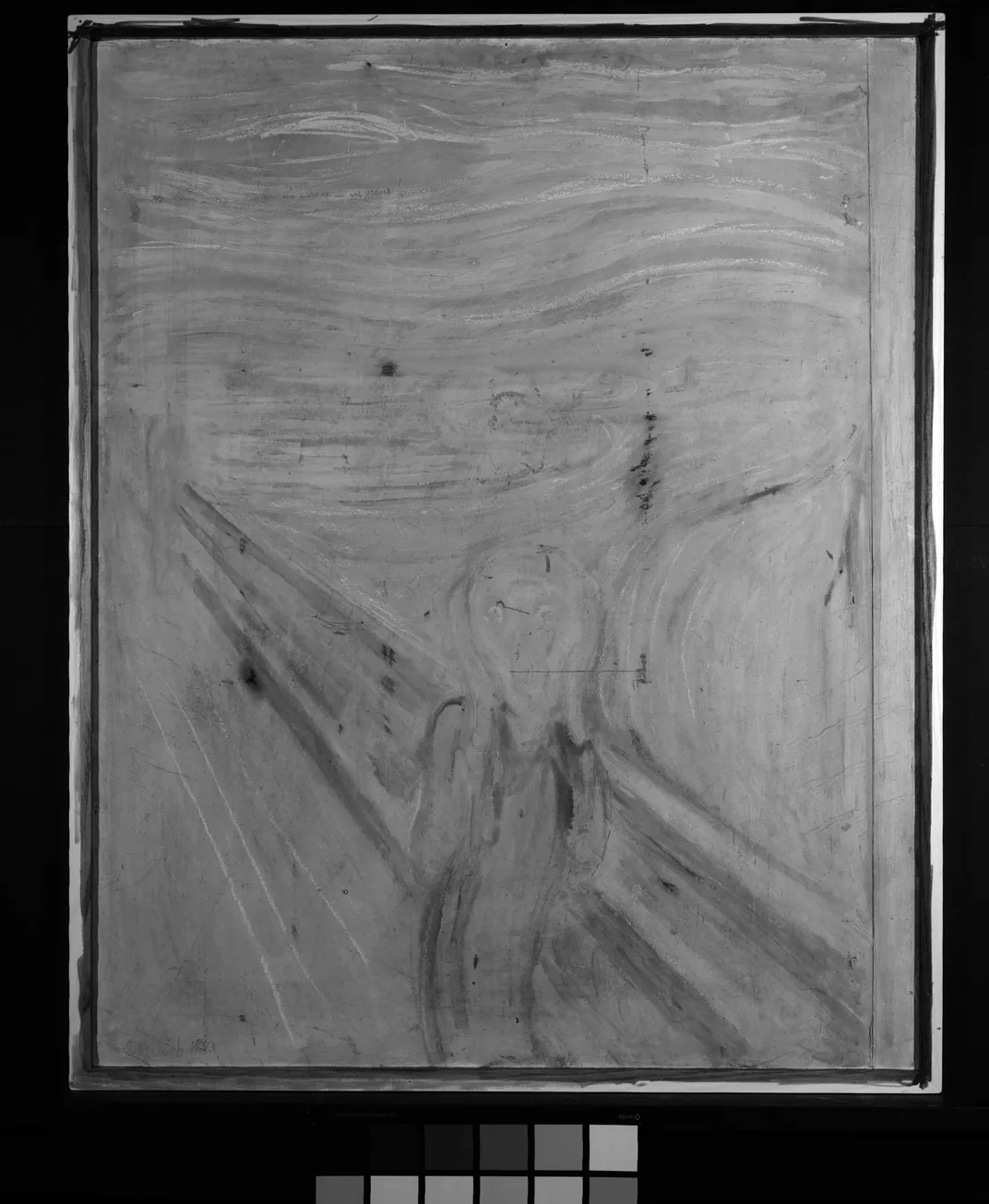

Nina Siegal of the New York Times reports that the findings illuminate the complicated backstory behind one of the most famous Expressionist masterpieces in the world. Munch painted four versions of The Scream between 1893 and 1910, placing a strange, skeletal figure against an eerie backdrop evocative of the psychological anxiety of modern life. The 1893 version in the Oslo museum’s collection, painted in tempera with pastels, is the original. (The back of this work’s panel features a partial composition that Munch later rejected, turning the work over to create the enduring image seen today, per the statement.)

Researchers first noted the existence of the strange graffiti in 1904, when The Scream was exhibited in Copenhagen. Curators at the time assumed that an outraged member of the public had penned the message.

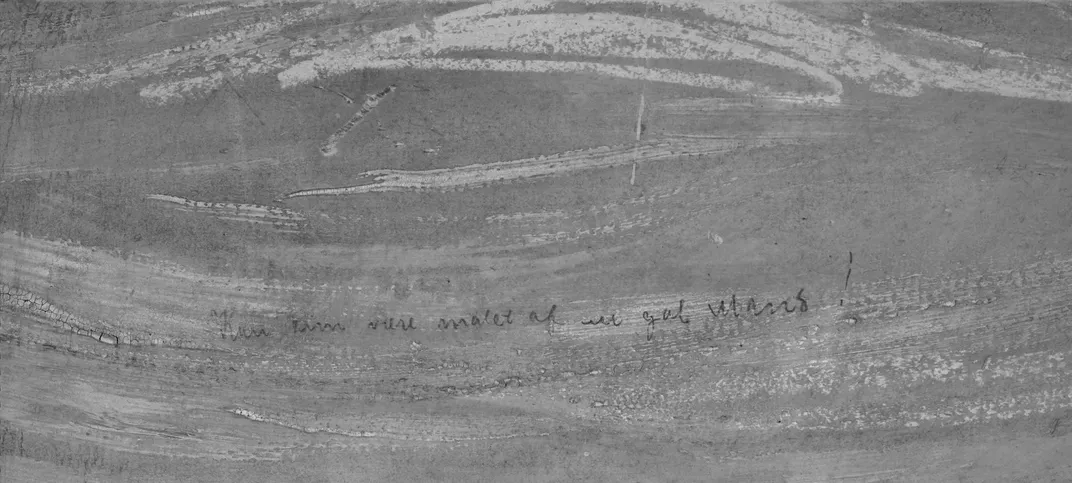

This year, museum staff taking part in a restoration project used infrared photography to take a closer look at the 1893 work and its inscription. (According to Rob Picheta of CNN, the work has been undergoing extensive conservation in anticipation of its move to a new museum slated to open in Oslo in 2022.)

Infrared light rendered the contours of the handwriting easier to identify. As Lasse Jacobsen, a research librarian at the Munch Museum in Oslo, tells the Times, a number of quirks link the graffiti to the artist.

“There are some letters in his handwriting that are really distinct, like the N, or the D, which turns up at the end,” he says. “So when I saw it there I thought, ‘This is Munch.’”

Another characteristic supporting the attribution is the size of the scribble.

“He didn’t write it in big letters for everyone to see,” Mai Britt Guleng, a curator at the National Museum, tells the Times. “You really have to look hard to see it. Had it been an act of vandalism, it would have been larger.”

Guleng adds that the handwriting is “identical” to samples of Munch’s handwriting from his diaries and letters.

“The writing is without a doubt Munch’s own,” says the curator in the statement.

If Munch did pen the idiosyncratic inscription, then the researchers’ proposed timeline would appear to align with historical events. In 1895, Munch exhibited The Scream to Norwegian audiences for the first time, showing it at the Blomqvist gallery in Oslo. Per the statement, art critic Henrik Grosch, director of the Norwegian Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, decried the painting as an indication that one could “no longer consider Munch a serious man with a normal brain.”

Negative reviews such as these prompted a group of students to hold a public debate about Munch’s work. Some members, including poet Sigbjørn Obstfelder, praised his oeuvre. But medical student Johan Scharffenberg argued that Munch’s paintings—particularly Self-Portrait With Cigarette—had given him reason to question the artist’s sanity, reports Gareth Harris for the Art Newspaper.

Munch, who was likely present at the meeting, was deeply hurt by these comments, writing about them in his diaries as far after the fact as the 1930s, according to the statement. The artist suffered from severe anxiety in an age when mental illness was still heavily stigmatized, and rumors about his mental state were circulated widely.

As Lanre Bakare writes for the Guardian, Munch became obsessed with disease after watching his mother and sister die of tuberculosis when he was a child. Mental illness also ran in his family: The artist’s older sister was admitted to an asylum with bipolar disorder, notes BBC News, and both his father and grandfather suffered from what was then known as “melancholy,” per the statement.

Researchers now believe that Munch added the comment in pencil sometime around 1895, in response to Scharffenberg’s comments and public speculation about his health.

This witty, ironic inscription was “very important for [Munch] to take control of his own self-understanding and also how others understood him,” Guleng tells the Guardian. “This was maybe an act of taking control because others had said that he was mad.”

In the face of widespread stigma about mental illness, Guleng adds, the message may have been Munch’s way of saying, “I can make a joke about that.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)