Why Are Our Brains Wrinkly?

Brain wrinkles naturally develop as the brain gets larger in order to lend more surface area and help white matter fibers avoid long stretches

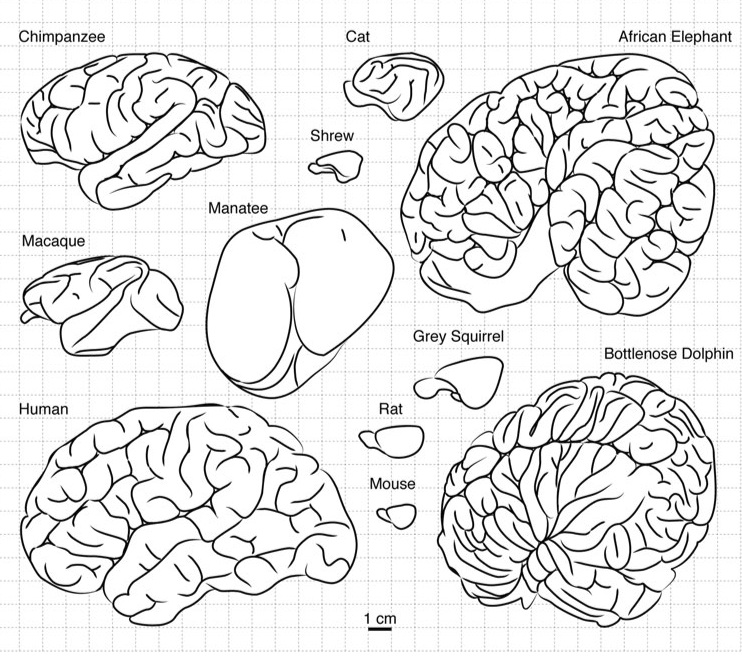

A smattering of mammalian brains. Photo: Toro et al, Evolutionary Biology

Manatee, rat and squirrel brains look more like a liver, smooth and slightly triangular, than what we think of as a brain. Dolphin brains, on the other hand, are notably crinkled, with what appears to be about twice the folds of a human brain. So what causes these differences? Is function or form to blame?

According to new research published in Evolutionary Biology it’s a bit of both. Carl Zimmer explains at National Geographic how the wrinkles come into play:

The more wrinkled a brain gets, the bigger the surface of the cortext becomes. The human brain is especially wrinkled. If you look at a human brain, you only see about a third of its surface–the other two-thirds are hidden in its folds. If you could spread it out flat on a table, it would be 2500 square centimeters (a small tablecloth). A shrew’s brain surface would be .8 square centimeters.

Those wrinkles, Zimmer explains, provide extra surface area for our oversized brains to take advantage of.

But there’s another intriguing thing about those wrinkles: they are not spread uniformly across our heads. The front of the neocortex is more wrinkly than the back. This is intriguing, because the front of the cortex handles much of the most abstract sorts of thinking. Our brains pack extra real estate there with additional folds.

Wrinkles also help larger brains keep their white matter fibers that link different areas of the cortex in order. As brains grow larger, white matter fibers must stretch longer. The wrinkles help keep these fibers packed more closely together: they are, Zimmer writes, “a natural result of a bigger brain.”

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)