Why Gala Dalí—Muse, Model and Artist—Was More Than Just Salvador’s Wife

Barcelona exhibition draws on 315 artifacts to unravel the myths behind central surrealist figure

:focal(1259x1069:1260x1070)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/10/98108c78-5855-4f30-9afe-3929fd4124cd/gala_placidia_esferes.jpg)

Gala Salvador Dalí: A Room of One’s Own in Púbol, a new exhibition at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona, derives its name from Virginia Woolf’s similarly titled 1929 essay, which proclaims that “a woman must have money and a room of her own” to create.

To Gala Dalí, this room of one’s own was Púbol, a Catalan castle gifted to her in 1969 by her famous husband Salvador. As Raphael Minder notes for the New York Times, Salvador was only allowed to visit the castle if he received a written invitation from his wife. Here, in the privacy of her own space, Gala, who was born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, reconstructed memories of her Russian past, assembling a collection of family photographs and Cyrillic texts, and documented life with Salvador through surrealist books, clothing and assorted keepsakes.

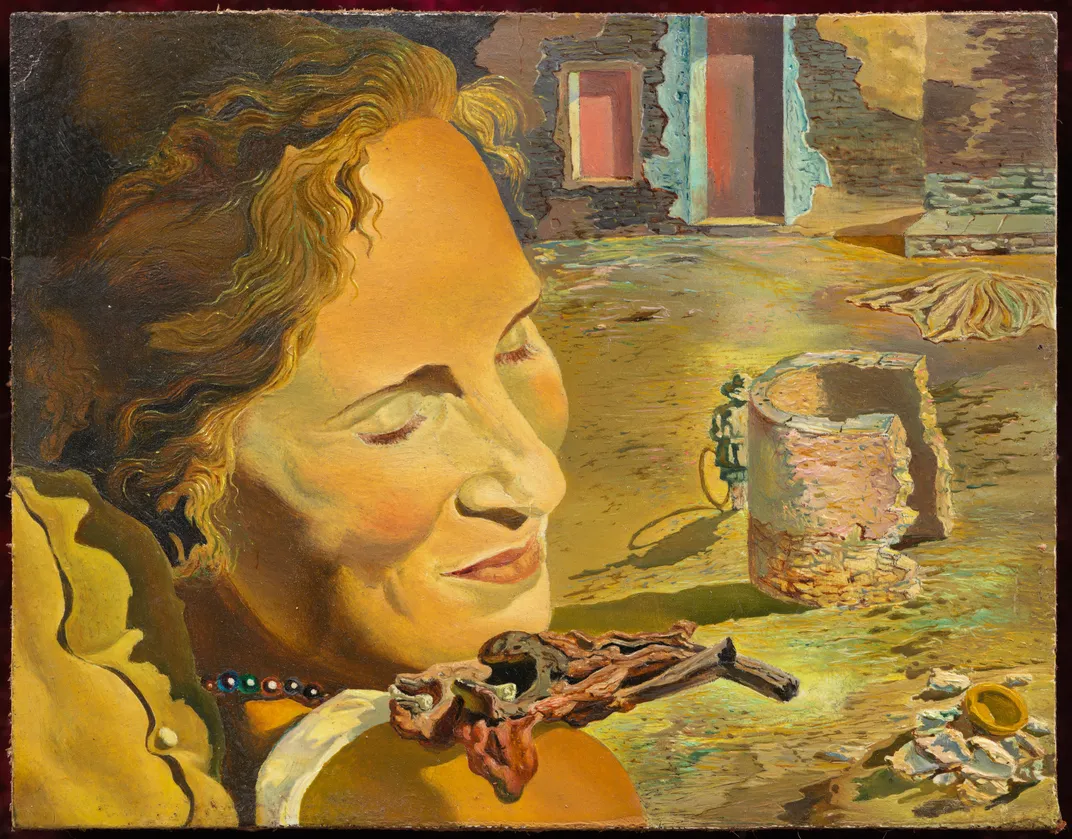

Simultaneously muse, model, artist, businesswoman, writer and fashion icon, Gala has long been treated as a cipher by art historians, but thanks to the new Barcelona exhibition, she is finally emerging as a singular individual connected with—but not dependent on—the male surrealists who surrounded her.

According to a press release, Gala Salvador Dali relies on a selection of letters, postcards, books and clothing derived from Púbol, as well as 60 of Salvador’s paintings and works by fellow surrealists Max Ernst, Man Ray and Cecil Beaton. Armed with 315 artifacts linked with the enigmatic figure’s life, curator Estrella de Diego set out to answer the following questions: “Who was this woman whom everybody noticed…Was she simply an inspiring muse for artists and poets? Or, despite having few signed pieces … was she more of a creator?”

Gala’s story begins with her birth in Kazan, Russia, in 1894. Well-educated despite living in a region where higher education was forbidden to women, she suffered from poor health and was sent to a Swiss sanitorium after being diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1912. Here, Gala met French poet Paul Éluard, who soon became her first husband and the father of her only child, a daughter named Cécile. By 1922, Gala had begun an affair with Max Ernst, who was so enamored with her that he featured her as the only woman in a group portrait of prominent surrealists.

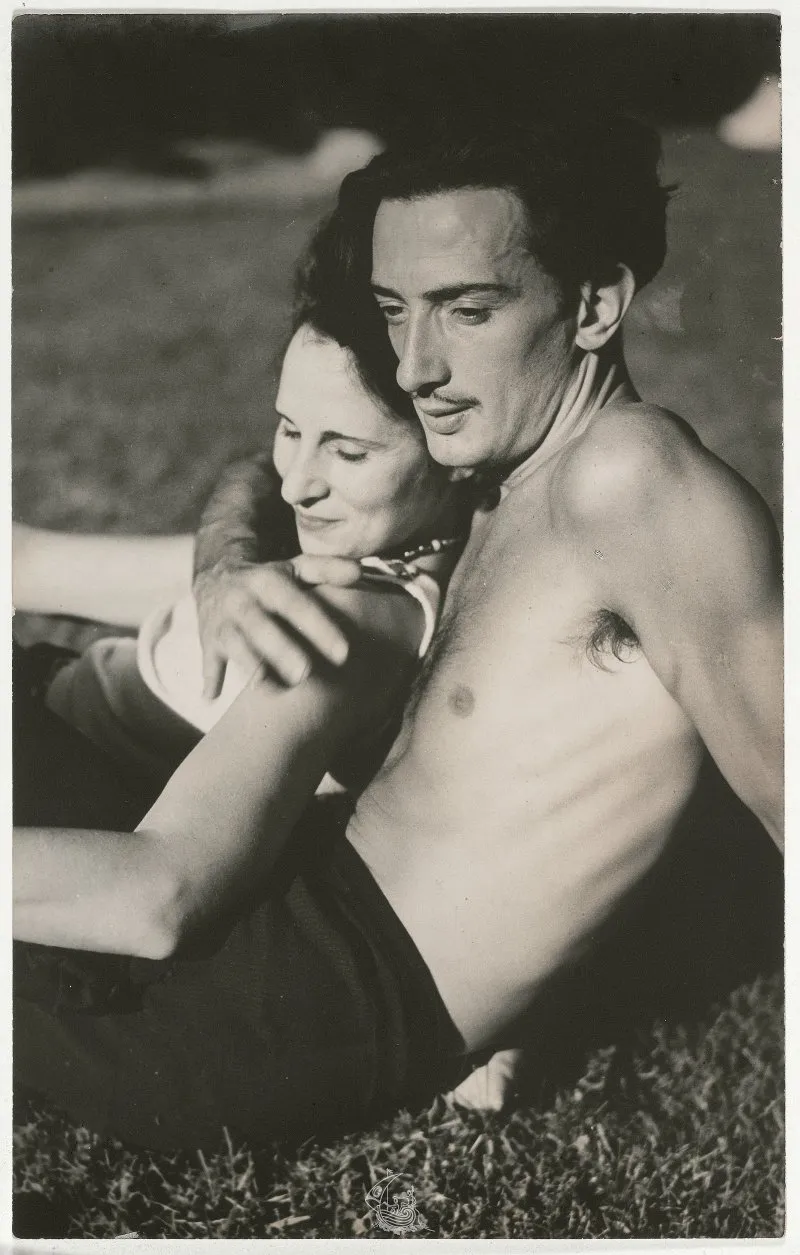

Seven years later, Gala visited Cadaqués, Spain, where she first met emerging artist Salvador Dalí. They had instantaneous chemistry, with Salvador later writing, “She was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife.” Gala left Éluard, and by 1934, had officially become Gala Dalí.

It’s at this point that the long-held notion of Gala as a greedy social climber (in a 1998 article, Vanity Fair’s John Richardson described her as “the demonic dominatrix” of Salvador’s dreams) departs from the narrative offered by the Barcelona exhibition. As the show’s curator, de Diego, tells the Art Newspaper's Hannah McGivern, Gala abandoned her life with Éluard to be with “a very young artist who nobody knew at that time, [living] in Catalonia in the middle of nowhere.”

By all accounts, Salvador was enraptured by his new wife, whom he nicknamed Gradiva, after the mythological heroine who serves as the driving force of Wilhelm Jensen’s eponymous novel; Oliva, for her oval-shaped face and suntanned skin; and Lionette, “because when she gets angry she roars like the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion."

As Salvador rose to fame, Gala was at his side, acting as agent, model and artistic partner. She read tarot cards in hopes of predicting Salvador’s career trajectory but was also eager to follow more practical paths, negotiating with gallery owners and buyers to maximize her husband’s earnings. According to the New York Times’ Minder, Gala was so persuasive in this role that another surrealist, the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico, asked her to serve as his agent, too.

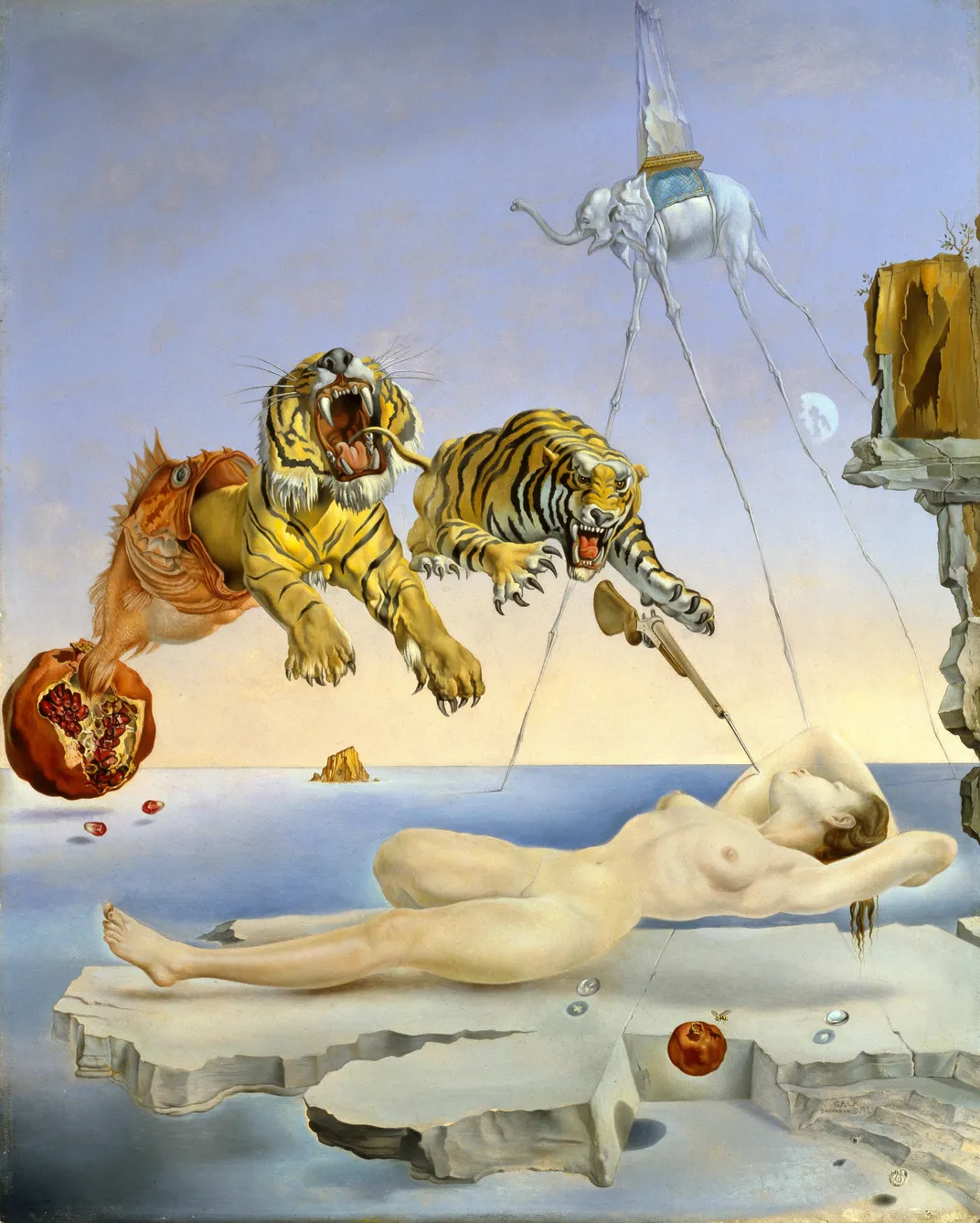

Alternatively cast as the Virgin Mary, a "Venus of Urbino"-esque reclining figure and a dark, enigmatic woman, Gala appeared in hundreds of her husband’s drawings and paintings. Soon, Salvador even started signing works with their joint signature, “Gala Salvador Dalí,” in honor of his belief that it was “mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures.”

There’s no evidence that Gala actually shared her husband’s paint brush (although she did contribute to his 1942 autobiography and other written works), but as the museum notes, she was very much the joint author of Salvador’s oeuvre: “It was she who chose the image with which she wanted to present and, especially, represent herself. It is possible to design one’s own self-portrait without producing a tangible pictorial work.”

Through the influence she wielded over Salvador and their circle of artist friends—as well as the surrealist texts and objects she produced herself—Gala had an enormous impact on the development of avant-garde art. She “found her place within a surrealist movement that otherwise made little room for women,” Minder notes, and remained unabashedly independent throughout her later years, conducting multiple affairs with young men in the privacy of her Púbol castle.

Upon her death in 1982, Gala was interred at Púbol in a chess board-like crypt designed by Salvador, who would outlive her by seven years. Although the Dalí Universe website states that Salvador ordered the construction of a pair of tombs “with a little opening between the two, so they could hold hands beyond death,” the painter was eventually buried separately in his hometown of Figueres.

Just as historians have struggled to build an accurate image of Salvador—writer Ian Gibson tells Vice’s Beckett Mufson that “he’s a biographer’s nightmare. What can you do with an individual who is always acting, always playing a part?”—the new exhibition is not able to unearth the complete story of Gala’s life. Still, the collection offers one of the first comprehensive glimpses of her story, and in doing so, reveals that she was a singular powerhouse in her own right.

“[Gala] always felt more comfortable in the shadows, but like Dalí she also wanted to become a legend one day,” Dalí Museums director Montse Aguer explained in a statement. “This mysterious, cultured woman, a gifted creator, colleague and peer of poets and painters, lived her art and her life in an intensely literary manner. … [She was] Gala, an elegant and sophisticated woman, acutely aware of the image she wanted to project. Gala, the focal point of mythologies, paintings, sketches, engravings, photographs and books. Gala Salvador Dalí.”

Gala Salvador Dalí: A Room of One’s Own in Púbol is on view at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona through October 14, 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)