Why a Campaign to ‘Reclaim’ Women Writers’ Names Is So Controversial

Critics say Reclaim Her Name fails to reflect the array of reasons authors chose to publish under male pseudonyms

:focal(807x540:808x541)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/b7/ceb72e39-d75c-47c0-914b-03d46f92fc4e/reclaim_her_name.jpg)

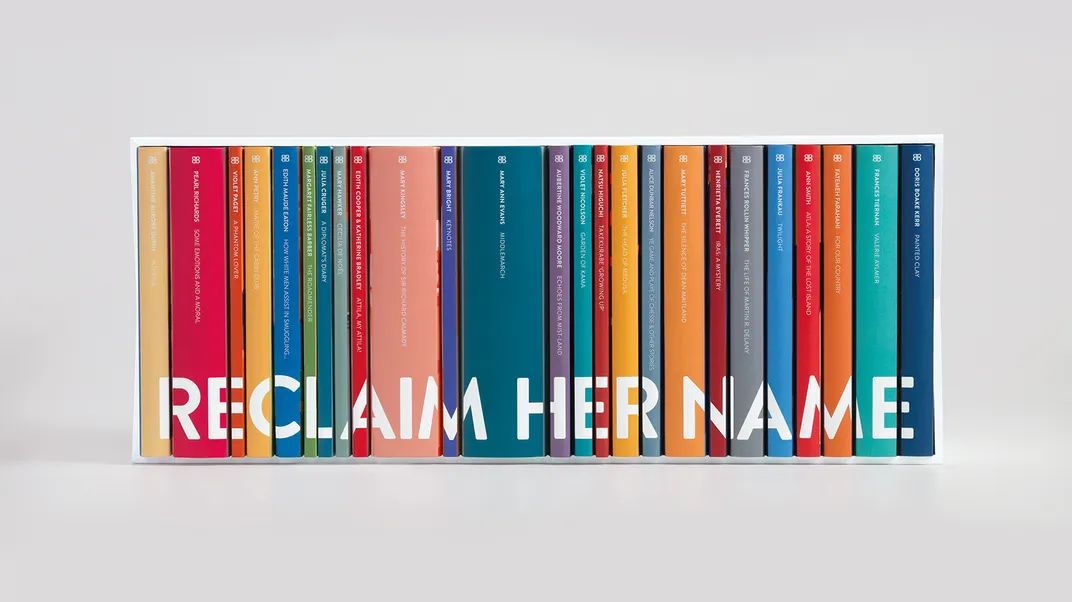

Last week, the Women’s Prize for Fiction and Baileys (best known for its Irish cream liqueur) launched Reclaim Her Name, a joint initiative honoring the literary award’s 25th anniversary. Billed as “finally giving female writers the credit they deserve,” the campaign centered on 25 classic and lesser-known works by authors who historically wrote under male pseudonyms. To “reclaim” these titles—including George Eliot’s Middlemarch and Vernon Lee’s A Phantom Lover—organizers republished them as free e-books featuring the writers’ actual names on the covers.

“Throughout history, many female writers have used male pen names for their work to be published or taken seriously,” wrote Baileys on its website. “ … [W]e have put their real names on the front of their work for the first time to honor their achievements.”

Despite its arguably well-intentioned aims, Reclaim Her Name quickly attracted criticism from scholars and authors, many of whom cited a number of historical inaccuracies embedded in the project.

For one, the campaign republished The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany—an 1868 biography of the eponymous journalist by African American writer Frances Rollin Whipper, who originally wrote under the name Frank A. Rollin—with a redesigned cover featuring abolitionist Frederick Douglass instead of Delany.

Bailey’s later removed the incorrect cover and apologized for the error.

“We are very sorry to say that a mistake was made at the launch of the Reclaim Her Name Collection,” the brand said. “This was caused by human error at our agency VMLY&R and we should also have spotted this in our reviews.”

In addition to this obvious oversight, numerous scholars took issue with the claim that women writers needed to publish under male pen names to be recognized for their work.

As writer and critic Catherine Taylor explains in the Times Literary Supplement, the truth is much more nuanced: “[This] one-size-fits-all approach overlooks the complexities of publishing history, in which pseudonyms aren’t always about conforming to patriarchal or other obvious standards.”

Writing for Literary Hub, Olivia Rutigliano points out many women writers, including Mary Wollstonecraft and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, published under their own names. Others chose female pseudonyms or adopted male monikers as a form of self-identification.

Lesbian and feminist Vernon Lee, for instance, chose to “cast off” her given name, Violet Paget, entirely. Likewise, writes Taylor, “It was Sand who was the novelist, not [Amantine Aurore] Dupin. ‘George Sand’ was as much a part of her image as the men’s clothes she wore and the tobacco she openly smoked.”

Rutigliano argues that the choice to republish authors under their so-called “real” names erases their agency, ignoring “their own decisions about how to present their works, and in some instances, perhaps even how to present themselves.”

Grace Lavery, a literary scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, also weighed in on the project: “C19 authors were not forced to use masculine pseudonyms; literary writing has always been a practice of imaginative self-fashioning,” she noted on Twitter. “However well-intentioned, this project undermines the towering literary work of George Eliot, Vernon Lee and others.”

In a 2019 blog post, Lavery explained that Eliot, born Mary Anne Evans in 1819, “relished being thought of as male, and was disappointed when people thought otherwise.” The only reason Eliot is typically referred to as “she,” according to Lavery, is because Charles Dickens outed her in a widely circulated 1858 letter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/41/88410958-d771-4f4c-b761-316338d8b6bc/george_eliot_por_francois_dalbert_durade.jpg)

Even the name of the Baileys campaign—which uses the “her” pronoun to refer to its authors—assumes the complex historical gender identities of these authors, says Rutigliano.

Another criticism of the project is its conflation of choices made by Victorian authors with those made by writers who hailed from different time periods and cultures. One of the 25 “reclaimed” titles is a short story attributed to Edith Maude Eaton, a Chinese-English writer who wrote about racial discrimination in the late 19th-century United States. As scholar Mary Chapman tells the Guardian’s Sian Cain, the author published under multiple monikers—including her Chinese name, Sui Sin Far—and may not have even written the work of fiction included in the project. She did, however, write another travelogue under a male pseudonym “that would have been a better fit” for the project, according to Chapman.

“I don’t think it is erasure to call her Eaton,” she adds. “[B]ut by not writing about her Chinese heritage with nuance, like in this project, it takes away the value of her having asserted her ancestry, which at the time was very important because Chinese people were treated very badly in North America.”

Women used pseudonyms to express creativity, align with queer identities, make money and an array of other reasons, writes scholar Sophie Coulombeau on Twitter. The ways in which contemporary writers and publishers name historical figures is “tricky, knotty & problematic,” she continues. “ … One size of grand reclamatory gesture does not fit all women. It feels ham-fisted to lump all these women together and sell them as a ‘reclaimed’ set.”

Coulombeau concludes, “[I]f I’d been asked, I’d have advised strongly against it.”

Editor’s Note, August 24: This article has been updated to more accurately reflect Edith Maude Eaton’s oeuvre.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)