SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

The Tradition of Now: Jainism, Jazz, and the Punjabi Dhol Drum

While the originations of the dhol are not known with complete certainty, what is known is that it is a sound that has migrated.

:focal(600x400:601x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/red-baraat-wedding.jpg)

“Tradition” is a concept I’ve grappled with much of my life, first as a child of immigrants growing up in America with Jainism, and then in becoming a music maker. The natural tendency with a tradition is that it creates a forcefield, ostensibly to preserve customs. For me, questioning a hundred-year-old tradition was not often in my mindset. But when I did, “because it’s tradition” was frequently an answer I received from my mother.

I was drawn to the rhythms of India at a very young age from the bhajans (devotional songs) and Bollywood songs I was surrounded by. My learning began at age ten in school with symphonic percussion before quickly gravitating toward jazz drums. One reason I never became fully immersed in studying tabla is because the traditional guru-student hierarchy didn’t gel with me. I suppose starting that journey at age eighteen made me rebel against that type of student-teacher relationship.

Meanwhile, I was diligently studying jazz drums in university where my professors were giving me the building blocks for my future—theory, composition, arranging—all while empowering me to find myself. “Study the masters, emulate them, then find your own voice” was the echoing message.

When you look at the history of jazz, it’s very much a migration of sound. The roots of the blues can be traced back to Senegalese field hollers. Enslaved Africans and their experience in the immigrant melting pot of New Orleans spawned jazz. This music made its way up the Mississippi River, spread around the States and eventually the world, and is now known as “America’s classical music.”

There is now an established musical vocabulary, a tradition, that we learn when studying jazz, but we also learn that improvisation and “the moment” is of utmost importance. This spontaneity is why the music developed and is also the thread that weaves through all the different styles of jazz. How ironic that what’s now considered a “traditional” music was paved by being in the “now.”

Shortly after many failed attempts at tabla, I fell in love with the folk drum of Punjab: the dhol. It is a barrel-shaped, double-headed, wooden shell drum, slung over the shoulder and known for being played during farming, dancing, and special occasions. It is a loud, festive, beautiful drum synonymous with Punjabi culture. While the originations of the dhol are not known with complete certainty, what is known is that it is a sound that has migrated.

The dhol is believed to have been introduced to the Indian subcontinent by the Islamic dynasties of the thirteenth century and possibly stems from the Persian drum, dohol. The dhol was first referenced as early as the sixteenth century in the courts of the Mughal emperor, Akbar the Great, and written about in Punjabi literature many times in the seventeenth century. In the 1970s, the dhol gained prominence within the diaspora in the UK with a commercial type of music called Bhangra, originally a term reserved for Punjabi folk dance and music.

I started on dhol in 2003 with a dozen or so lessons from a friend, Dave Sharma, and then continued the journey learning from recordings, YouTube videos, and one-off lessons during visits to India. I used to spend hours a day practicing dhol on a viaduct in Harlem, while the two Punjabi-owned gas stations below made me feel connected to the motherland with their encouraging hollers. I delved into the folk rhythms of Punjab by revisiting music from childhood.

When I joined the Sufi rock band Junoon in 2006, I quickly became obsessed with the Sufi dhol drummers of Western Punjab, located in Pakistan. Some of the masters I watch online regularly are Pappu Sain, Nasir Sain, Gunga Sain, Mithu Sain (“Sain” is an honorific term). Regardless of these fantastically differing approaches by dholis from Eastern Punjab (India) and Western Punjab (Pakistan), what’s clear is the centrality of this drum in Punjabi sensibility.

My jazz background has always informed how I play the dhol. Having first studied the traditional rhythms of the dhol, I started practicing along with Gurdas Maan and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan albums. Next came Miles Davis records (the first quintet with “Philly” Joe Jones on drums), and using Ted Reed’s Syncopation drum book to inspire exercises. I began jamming with various musicians in New York City, namely Marc Cary and Kenny Wollesen. And of course, my band Red Baraat has given me thirteen years of joyful performance and composition from a dhol perspective.

In recent years, I’ve been using various pedals and effects made by Eventide to process my sound and blend it with natural acoustic sound. A lot of this gets realized on my solo album Wild Wild East, released this year by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

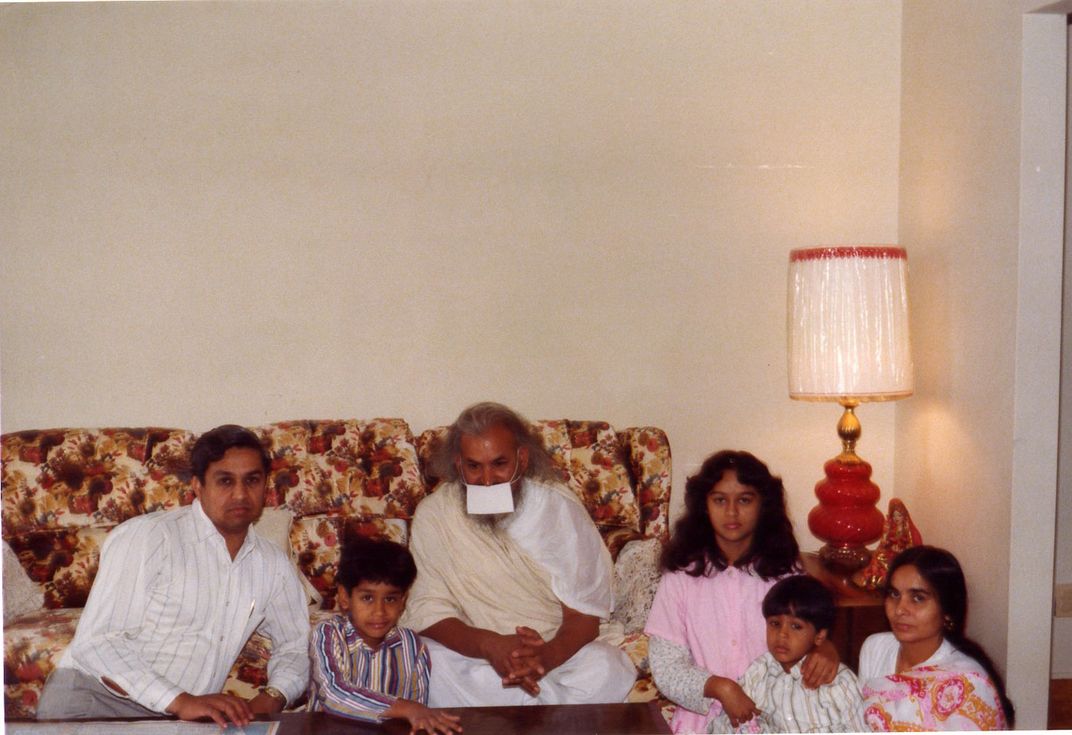

My family comes from Osian, a small village in Rajasthan, India. They migrated in the twelfth century to Punjab after invasions. Finding a home in the city of Sialkot in the state of Punjab, they adopted Punjabi culture while retaining their Jain religion. Being Punjabi Jain is an anomaly. When India and Pakistan gained independence on August 15, 1947, the resulting partition divided the state of Punjab as the British exited the subcontinent: Western Punjab for Pakistan and Eastern Punjab for India. This caused the largest mass migration in world history over religious lines. The UN Refugee Agency estimates 14 million people were displaced—my parents among them.

My parents eventually became the only people in their families to immigrate to America. I was born in Rochester, New York. My parents held on strong to traditions, specifically the rituals and teachings of Jainism, a religion that dates back to 3000 BCE and teaches ahimsa, or nonviolence, as one of its main tenants. It’s because of this that Jains are vegetarian or, nowadays, vegan, not wanting to harm animals. Nonviolence also extends to protecting the Earth and living via minimal consumption because any impact affects the world’s ecosystem.

Another belief of Jainism is anekantvada, or multiplicity of viewpoints. This philosophy resonates with me and is reflected in my approach to music. My aim is to blur the boundaries and not adhere to genre, but rather bring different musical forms into conversation with one another. As a jazz-drumming vegetarian Jain child of Punjabi immigrants, there wasn’t a model to look to on how to navigate life in Rochester. This is what propelled me to find my musical identity not just within the structure of traditions but also in the breaking of them.

With Wild Wild East, I looked to my family history for the overarching concept. Our story of migration had to be reflected in sound and encompass multiple identities. I looked to musical traditions or genres for inspiration, such as jazz, Rajasthani and Punjabi folk music, Ennio Morricone’s Spaghetti Westerns, hip-hop, and shoegaze. I then slowly migrated away from their established structures over the course of composition, recording, and shaping of sound.

During the entire process of this album, my father’s health was declining, and he eventually passed on November 14, 2019. It was an extremely intense and sad time. Customs and traditions came to the forefront very quickly as his ashes needed to be taken back to India. We had to reconcile what he would have wanted versus what cultural traditions were dictating.

I’m left still grappling with the idea of tradition, what it means to me now, and what I will and won’t pass onto my kids. The values of Jainism have shaped my core, and the musical traditions of South Asia are in their DNA. So they will get those for sure. But the one lesson jazz has taught me—being in the moment, allowing for fluidity and maintaining open communication and trust with others—that is one tradition I will pass onto my children with certainty.