Bird Migrations, Floral Blooms and Other Natural Phenomena Cause Seasonal Spikes in Wikipedia Searches

A new study has found that pageview trends for various plants and animal species correspond to real-world seasonal patterns

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/b2/66b2f301-b529-41d2-bef2-dee23313fd3a/istock-532394266.jpg)

In this internet age, we spend a lot of time plugged into phones and computers. But, somewhat ironically, the way we use Wikipedia suggests that we are still in tune with nature. As Anna Groves reports for Discover, a new study has found that Wikipedia pageview trends for various plants and animals match the species’ seasonal patterns, indicating that people are very much aware of and interested in the world beyond their phone screens.

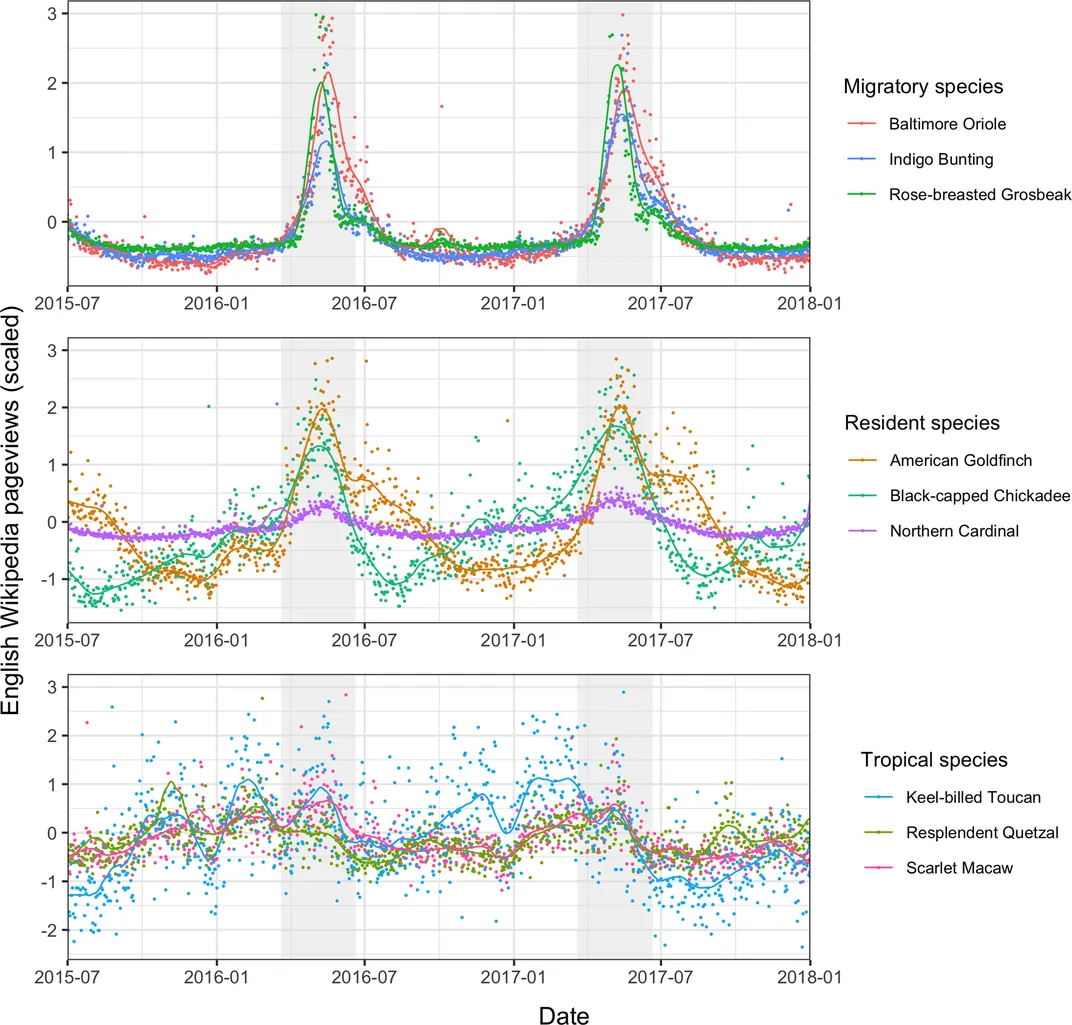

The study, published in PLOS Biology, looked at a huge dataset of 2.33 billion pageviews for 31,715 species in 245 languages. More than a quarter of the species in the dataset showed “seasonality” in pageview trends in at least one of their language edition pages. So, for instance, the researchers found that pageviews for three migratory birds—the Baltimore oriole, the indigo bunting and the rose-breasted grosbeak—spiked during the times when these animals pass through the United States. Pageviews for bird species like the American goldfinch and northern cardinal, which reside in North America year-round, did undergo fluctuations over the course of the year, but did not surge during specific seasons.

Similarly, pageviews for flowering plants had stronger seasonal trends than those for coniferous trees, which tend to require an expert eye to spot their yearly changes. There were also “significant” differences between language editions, the researchers write. Species pages written in languages spoken at higher latitudes—like Finnish and Norwegian—showed more seasonality than pages written in languages spoken in lower latitudes—like Thai and Indonesian—where seasons are less distinct.

“For some species, people are paying enough attention to when a bird arrives on its breeding grounds, or when a particular plant flowers,” John Mittermeier, lead study author and PhD student at the University of Oxford, tells Groves. “The fact that people are really responding to that is cool.”

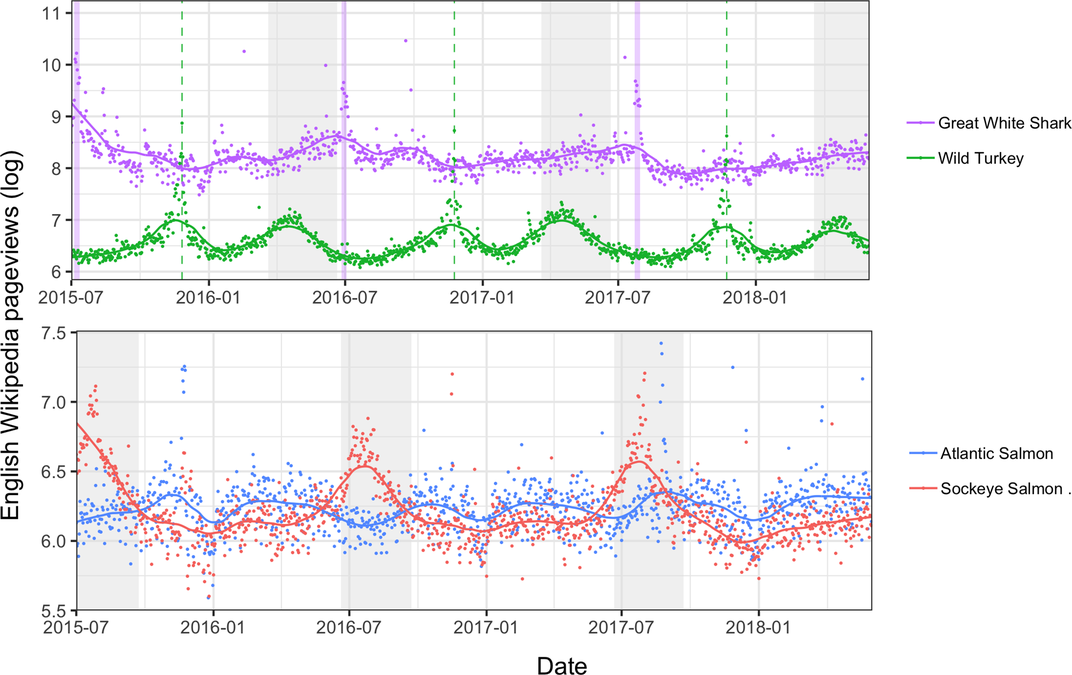

The dataset included a number of random Wikipedia articles, which did not show significant seasonality when it came to pageviews. This drove home the researchers’ theory that “human interactions with nature are particularly likely to be seasonal.” In some cases, pageview patterns seemed to be sparked by cultural events. During “Shark Week,” for instance, English-language pageviews for the great white shark went up. Views for wild turkey pages peaked sharply during Thanksgiving and in the spring, which is turkey hunting season in many states.

The fact that people seem to be paying attention to the natural world around them is “really exciting” from a “conservation perspective,” says Mittermeier. For organizations planning fundraising campaigns, for instance, it could be helpful to target “flagship species” that are of particular interest during particular times. According to Richard Grenyer, study co-author and associate professor of biodiversity and conservation at Oxford, “big data approaches” like the one used in this study can thus help answer one of the most important questions facing conservationists today: “[W]here are the people who care the most and can do the most to help?"