120,000-Year-Old Cattle Bone Carvings May Be World’s Oldest Surviving Symbols

Archaeologists found the bone fragment—engraved with six lines—at a Paleolithic meeting site in Israel

:focal(358x297:359x298)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/e3/d5e313b0-f66f-491b-ad91-4241408384b5/bones.jpg)

Israeli and French archaeologists have found what may be one of humans’ earliest known uses of symbols: six lines inscribed on a bovine bone some 120,000 years ago.

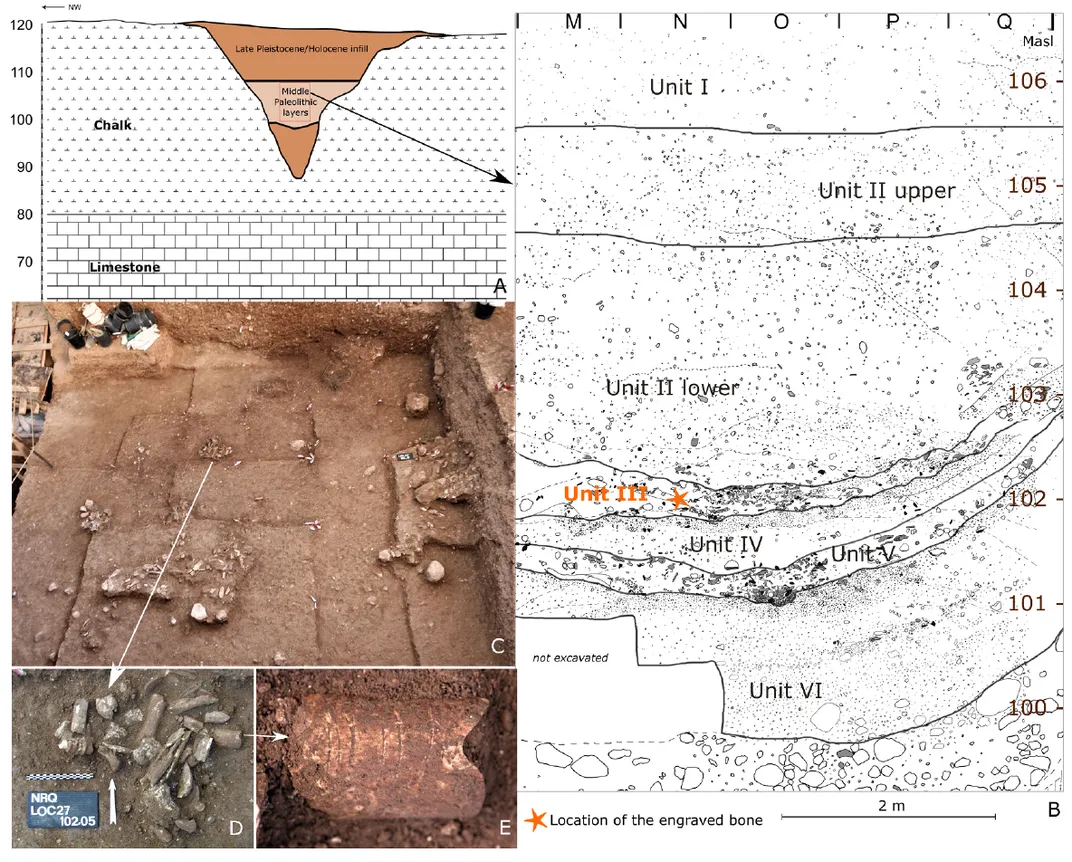

As Rossella Tercatin reports for the Jerusalem Post, scholars from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Haifa University and Le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique discovered the bone fragment at the Middle Paleolithic site of Nesher Ramla in Israel. The team published its findings this week in the journal Quaternary International.

“It is fair to say that we have discovered one of the oldest symbolic engravings ever found on Earth, and certainly the oldest in the Levant,” says study co-author Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology in a statement. “This discovery has very important implications for understanding of how symbolic expression developed in humans.”

Because the markings were carved on the same side of a relatively undamaged bone, the researchers speculate that the engravings may have held some symbolic or spiritual meaning. Per the statement, the site where researchers uncovered the fragment was most likely a meeting place for Paleolithic hunters who convened there to slaughter animals.

The bone in question probably came from an auroch, a large ancestor of cows and oxen that went extinct about 500 years ago. Hunters may have used flint tools—some of which were found alongside the fragment—to fashion the engravings, according to the Jerusalem Post.

Researchers used three-dimensional imaging and microscopic analysis to examine the bone and verify that its curved engravings were man-made, reports the Times of Israel. The analysis suggested that a right-handed artisan created the marks in a single session.

“Based on our laboratory analysis and discovery of microscopic elements, we were able to surmise that people in prehistoric times used a sharp tool fashioned from flint rock to make the engravings,” says study co-author Iris Groman-Yaroslavski in the statement.

Scholars are unsure of the carvings’ meaning. Though it’s possible that prehistoric hunters inadvertently made them while butchering an auroch, this explanation is unlikely, as the markings on the bone are roughly parallel—a methodical feature not often observed in butchery marks, per Haaretz’s Ruth Schuster. The lines range in length from 1.5 to 1.7 inches long.

“Making it took a lot of investment,” Zaidner tells Haaretz. “Etching [a bone] is a lot of work.”

Archaeologists found the bone facing upward, which could also imply that it held some special significance. Since the carver made the lines at the same time with the same tool, they probably didn’t use the bone to count events or mark the passage of time. Instead, Zaidner says, the markings are probably a form of art or symbolism.

“This engraving is very likely an example of symbolic activity and is the oldest known example of this form of messaging that was used in the Levant,” write the authors in the study. “We hypothesize that the choice of this particular bone was related to the status of that animal in that hunting community and is indicative of the spiritual connection that the hunters had with the animals they killed.”

Scholars generally posit that stone or bone etchings have served as a form of symbolism since the Middle Paleolithic period (250,000–45,000 B.C.). But as the Times of Israel notes, physical evidence supporting this theory is rare.

Still, the newly discovered lines aren’t the only contenders for the world’s earliest recorded symbols. In the 1890s, for instance Dutch scholar Eugene Dubois found a human-etched Indonesian clam shell buried between 430,000 and 540,000 years ago.

Regardless of whether the carvings are the first of their kind, the study’s authors argue that the fragment has “major implications for our knowledge concerning the emergence and early stages of the development of hominin symbolic behavior.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)